Why do we feel more strongly about one option after a third one is added?

Decoy Effect

, explained.What is the Decoy Effect?

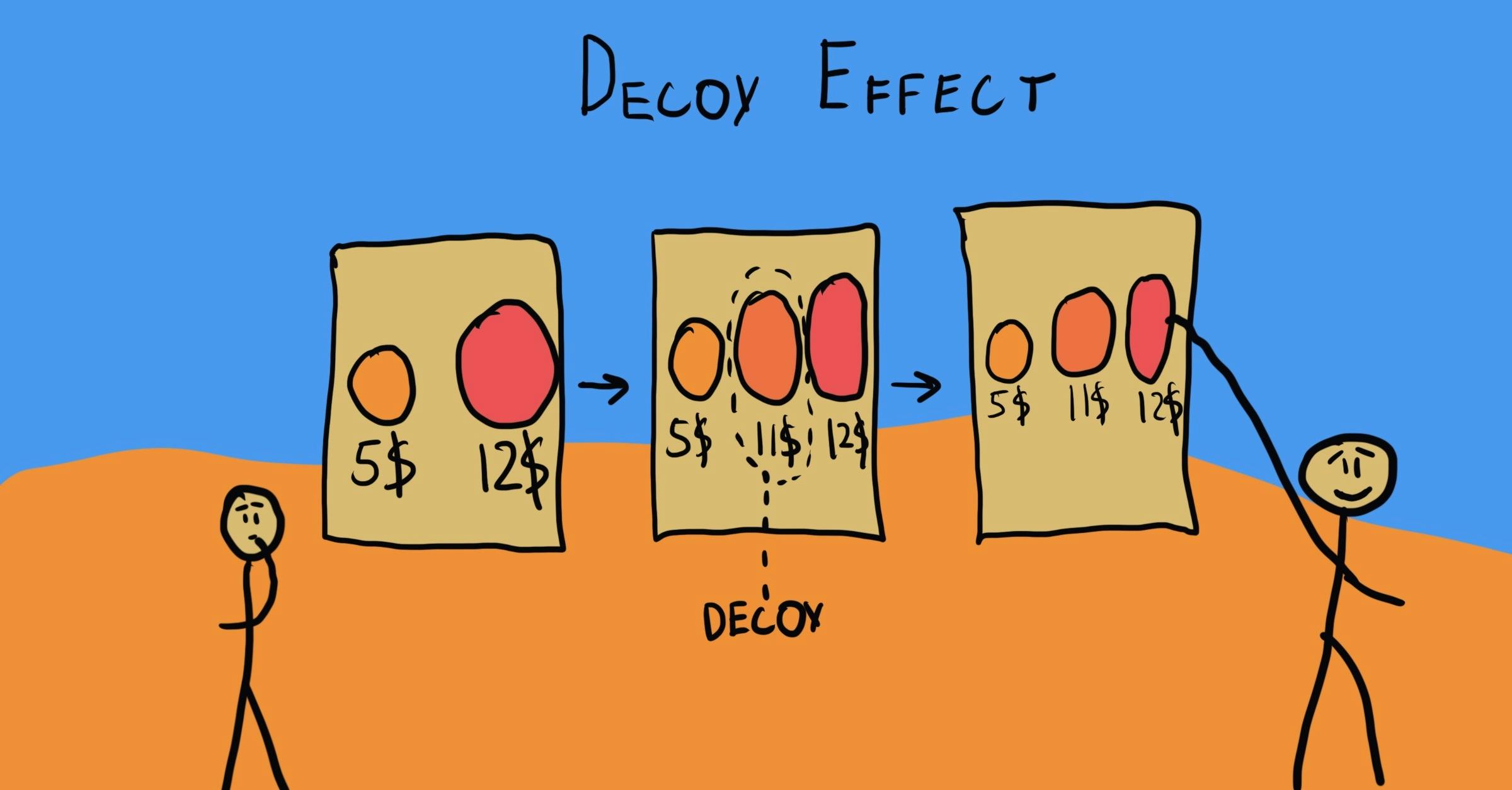

The decoy effect describes how, when we are choosing between two alternatives, the addition of a third, less attractive option (the decoy) can influence our perception of the original two choices. Decoys are “asymmetrically dominated:” they are completely inferior to one option (the target) but only partially inferior to the other (the competitor). For this reason, the decoy effect is sometimes called the “asymmetric dominance effect.”

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you’re lining up at a movie theater to buy some popcorn. You’re not all that hungry, so you think you’ll get a small-sized bag. When you get to the concession stand, you see the small costs $3, the medium is $6.50, and the large is $7. You don’t really need a whole large popcorn, but you end up buying it anyway because it’s a much better deal than the medium.

In this example of the decoy effect, we can consider the large popcorn as the target that the movie theater wants you to purchase, while the small popcorn is its competitor. By adding the medium popcorn as a decoy (since it is only 50 cents less than the large one), the movie theater persuasively convinces you to give in and make the bigger purchase instead.

Individual effects

The decoy effect can cause us to spend and consume more than we really need to. When a decoy option is present, we tend to make decisions based less on which option best suits our purposes and more on what feels like the most advantageous choice.

Unfortunately, following our intuition doesn’t always mean we’re making the smartest choice. Most of the time, the decoy effect leads us to pick a more costly alternative than we would have otherwise that really doesn’t add much additional benefit. In other words, what seems like a good deal in the moment often isn’t worth it in the end.

Systemic effects

Decoys are a commonly used tool by businesses and corporations to “nudge” us into buying more than we originally anticipated. Over time, this can add up to a big hit on our finances—and even our health. The product most commonly pushed with decoys are unhealthy foods such as soft drinks, the overconsumption of which can have serious health consequences. Sugary beverages increase our risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions.1 Unfortunately, they are far from the only processed food that employs decoys to upsell larger portion sizes.

How it affects product

Just like with junk food, the decoy effect can determine our digital purchases. When downloading an app or subscribing to a streaming service, we often choose between different tiers: basic, premium, or pro. Usually, we opt for “basic” since it’s free or only a few bucks, even if it has fewer options and has a bunch of ads. However, if we noticed that “pro” was only slightly more expensive than “premium” but unlocked several more features, we might be tempted to spend the extra money.

The decoy effect and AI

At the time of writing, AI software is not designed to intentionally manipulate consumers using the decoy effect. However, machine learning recommendations may inadvertently prompt asymmetric dominance anyways. For example, streaming services such as Netflix or Spotify have AI generated systems that personalize movies or music suggestions to your interests. If one recommendation is significantly worse than the rest, such as a genre you would typically never indulge in, it might actually encourage you to view the other suggestions as better tailored and stream them instead.

Why it happens

Before getting into the reasons why the decoy effect is so strong, we need to explain the concept of “asymmetric domination” more thoroughly. In a typical decoy situation, there are three choices available:

The target is the choice a business wants you to make.

The competitor is the option competing with the target that you might want to make.

The decoy is the option the business adds to nudge you towards choosing the target.5

The crux of the decoy effect is that the decoy must be asymmetrically dominated by the target and the competitor, with respect to at least two properties—let’s call these A and B. This means that the target is rated better than the decoy on both A and B, while the competitor might be better than the decoy on A but worse on B.

Let’s revisit the popcorn example from above. In this scenario, you, the customer, are evaluating your options based on two factors: size and price. The large popcorn is the target, and the small is the competitor. The medium popcorn works as a decoy because it is asymmetrically dominated by the other two. Although it is bigger than the small, it is also more expensive, making it only partially superior. The large, however, contains more popcorn and is only slightly more expensive than the medium, making it less expensive per unit.

This situation was actually used in an informal experiment by National Geographic. Although very few people purchased the large popcorn when their only other option was the small, once the medium was added as a decoy, the large became “irresistible.”

Decoys work subconsciously

The decoy effect is an example of a behavioral nudge—a type of intervention that “steers” individuals towards making a certain choice. Nudges do not manipulate behavior by providing large incentives to behave a certain way or threatening some form of punishment for failing to do so. Instead, they involve very subtle changes to an environment or situation, leveraging some aspect of human behavior to push us in the desired direction.3

As with all nudges, the decoy effect does not technically violate our free will because it doesn’t impose any restrictions on us, only subtle suggestions. Usually, decoys affect us without us even realizing it. Whatever we ultimately choose, we believe that we are doing so independently. In short, invisibility is part of what makes the decoy effect so powerful.

It may be hard to believe that factors outside our awareness influence our decision-making. However, research demonstrates that we are not very good at determining the reasons for our own behavior. Even though we believe we make all of our choices consciously and deliberately, we are often unaware of the factors that influenced us.

In one study, researchers had participants memorize pairs of words. After doing so, they completed a separate word association task, where they named examples of a certain type of object. The researchers designed some word pairs to elicit specific answers during the association task. For example, the pair “ocean–moon” was intended to prime participants to say “tide” when asked to name a type of detergent.

The word pair cues worked as intended: individuals exposed to a given prime were twice as likely to name the target word. However, when asked why they responded the way they did, very few participants mentioned the word pairs. Instead, their explanations focused on some defining feature of the target (“Tide is the best-known detergent”) or personal meaning associated with it (“I use Tide at home”).4 In short, researchers were able to nudge participants’ answers without them even realizing it. This explains how companies sneak the decoy effect underneath the surface of our consciousness while we rely on other excuses to explain our purchases.

Decoys provide a justification for our choice

In the Tide study, the word pairs influencing participants’ associations were well outside of their awareness—but that didn’t stop them from readily providing explanations for why they responded the way they did.

This leads us to an interesting point: when people make decisions, their goal is not to pick the correct option. Instead, the goal is to justify the outcome of a choice they’ve already made.5

In another study that specifically looked at the decoy effect, researchers asked participants to pick from sets of various products. As expected, when a decoy option was present, people were more likely to pick the target. However, this effect was even stronger if participants were informed they would have to justify their selection to other people afterwards.10 Why? Decoys provide an easy rationale for people to choose the target: they emphasize the pros of choosing the target and the cons of choosing the competitor. They make us feel comfortable in our choice by handing us a ready-made justification for it.

Decoys make choices feel less overwhelming

Decoys simplify decision-making in more ways than providing a nice-sounding explanation—they also alleviate anxiety when we have too many options to choose from.

The "paradox of choice" is a concept describing how the more options we have, the more difficult it is to make a decision. Although you would think a broader selection would simplify the process, we get overwhelmed when we have too many choices and experience more regret when we make the “wrong” one.11

There are a few reasons for this, but one most relevant to the decoy effect is preference uncertainty. When making any decisions, there are always numerous factors that we must take into account. The less certain we are about which ones to prioritize, the more difficult it will be for us to choose.6

To avoid preference uncertainty, people typically pick a small number of factors to focus on to judge their options—for example, price and quantity. The decoy effect capitalizes on this by manipulating the factors of interest.7 Preference uncertainty also makes it more likely that we will make a reasons-based choice—or in other words, choosing the option with the nicest-sound rationale attached to it.10

Decoys capitalize on loss aversion

We hate losing more than we like winning. Loss aversion describes how it’s usually more unpleasant to lose a given amount than it is pleasant to gain an equivalent sum.9 Finding $20 on the street will probably brighten your mood for a short while, but losing $20 out of your wallet may ruin your whole day.

However, what qualifies as a “loss” is not set in stone but is relative to some reference point. Decoys function by manipulating where this reference point is. Compared to the decoy, the competitor option (the option we are nudged away from) is advantageous in some ways and disadvantageous in others. However, loss aversion causes us to focus more on the disadvantages when deciding. As a result, we are more likely to pick the target.5

Research has also shown that people are more averse to lower quality than we are to higher prices.5 Decoys exploit this feature by pushing us towards a target that is a higher quality and a higher price.

Why it is important

To illustrate how the decoy effect can influence decision-making, consider this experiment conducted by psychologist Dan Ariely. Ariely was interested in the three options available for subscriptions to The Economist: $59 for an online subscription, $125 for a print-only subscription, and finally, $125 for both print and online access. He presented these options to his students and asked them all to pick one. 16% of the students chose the cheaper online subscription, 84% chose the print & web subscription, and nobody chose the $125 print-only subscription.

Next, Ariely removed the option nobody wanted—the $125 print subscription—and asked another group of students to pick from the remaining two. This time, 68% picked the $59 online subscription, and only 32% picked the print & web subscription. In Ariely’s words, “The most popular option became the least popular, and the least popular became the most popular.” In other words, even though the majority of the class would ordinarily be content with an online-only subscription, simply adding a decoy nudged them to spend almost $70 more on something they didn’t really need.

By adding a decoy to an array of products, companies can influence our decisions more than we realize—and this influence adds up over time.

From relatively inexpensive things like popcorn, to bigger purchases like airline tickets,5 decoys are everywhere. The decoy effect is made all the more pernicious by the fact that we do not realize we are being manipulated, instead feeling like we are making the logical choice.

How to avoid it

Another tricky thing about the decoy effect is that being aware of its existence probably is not enough to avoid it.5 After all, part of why this bias works so well is precisely because it feels rational. When we try to carefully examine our selection, we might just end up doubling down on our choice. That said, there are a few strategies out there to avoid falling into the trap of asymmetric dominance.

Figure out your preferences ahead of time

As discussed above, not knowing what factors to prioritize when making a decision makes us more likely to fall for the decoy effect.10 So when you need to buy something, take some time to figure out what qualities you value the most before browsing through your options. For example, maybe you are buying a new car, and you decide that gas mileage is more important to you than getting a low price. Having these preferences clearly established beforehand is good protection.

Only buy what you really need

The decoy effect doesn’t necessarily always push us into making a “bad” decision. In some cases, opting for a larger size or a higher-quality version of a given product might be more cost-effective in the long run. But other times, buying the more expensive target option will not satisfy our needs any better than a competitor would. Some good examples of this include the print & web Economist subscription described above, or unhealthy items such as combo fast food meals or extra-large cups of soda.

In cases like these, it is helpful to focus on the reason you are buying something in the first place. Ask yourself whether a larger or higher-quality version of a product is worth the extra money. Will it really satisfy that need any better than a cheaper alternative would? Sometimes the answer may be “yes,” but a lot of the time, it will probably be “no.”

Beware of sets of three

The decoy effect is most effective when there are only three options in play: target, competitor, and decoy.5 Whether you’re out shopping or even deciding between political candidates, try to notice when things crop up in groups of three—there may be a decoy in the mix.

Don’t trust your gut

Your individual thinking style plays a role in how likely you are to be affected by the decoy effect. One study, which involved more than 600 participants, found that the people most influenced by a decoy were the ones who tended to rely on intuitive reasoning.

The researchers behind this study used a questionnaire called the Rational-Experiential Inventory (REI) to gauge whether people were more rational or more intuitive in their decision-making.14 You can try filling out the REI yourself! Otherwise, simply ask yourself questions about how you normally solve problems. Do you believe in trusting hunches? Do you avoid thinking in depth about problems? If your answer to questions like these is “yes,” you might be an intuitive thinker. There’s nothing wrong with that—but if you’re looking to avoid the decoy effect, consider employing some of the strategies above.

How it all started

The concept of asymmetric dominance was coined by Joel Huber, John Payne, and Chris Puto. Before this point, dominant models of how people make decisions all abided by the regularity principle, or the idea that adding a new alternative to a set of options cannot increase the likelihood of choosing a member of the original set.8 In other words, psychologists and economists specifically believed that something like the decoy effect would be impossible because it violates the regularity condition.

Huber, Payne, and Puto ran an experiment where they asked participants to choose between various hypothetical alternatives. The decisions involved beer, cars, restaurants, lottery tickets, camera film, and television sets. For every scenario except the one involving lottery tickets, the presence of a decoy increased the percentage of people who said they would pick the target.8

These results challenged the regularity condition, as well as another concept called the similarity hypothesis. Proposed by Amos Tversky, the similarity hypothesis states that when a new product enters the market, it will disproportionately “cannibalize” the market share of items most similar to it. Put more simply, consumers will be split between the new product and older ones that have a lot in common with it. However, this does not happen in the decoy effect. Instead, decoys can boost the popularity of the alternative that it is closest to: the target.

Example 1 – Dating apps

The decoy effect not only determines how you evaluate brands on the store shelf, but also how you choose between options in the marketplace of love. Ariely, who conducted the Economist experiment above, has found that we tend to be more interested in people if we see them alongside a similar looking, but slightly less attractive, decoy.12

This effect is likely most relevant for people who use dating apps, such as Tinder or Bumble. When presented with a long stream of potential partners, there is a good chance that our decisions will be affected by the faces we have seen previously.

Example 2 – Politics

The decoy effect may also play a role in politics, specifically in political races with two frontrunners. Some psychologists have even argued that the decoy effect played a major role in the 2000 US presidential election through independent candidate Ralph Nader. Rather than take votes away from the democratic candidate Al Gore, as is commonly believed, Nader’s presence may actually have increased the number of votes cast for the candidate he more closely resembled: George W. Bush.2

Summary

What it is

The decoy effect describes how people’s preferences when picking between two options are altered by adding a third, relatively unattractive “decoy” option. The decoy is asymmetrically dominated, meaning that it is completely inferior to one option (the target) and somewhat inferior to the other (the competitor), making us more likely to choose the prior.

Why it happens

Decoys are a type of behavioral nudge, an intervention that subconsciously alters how we make decisions. Decoys capitalize on a number of weaknesses of our decision making processes: they make it easier to rationalize our intuitive choices, they make us feel less overwhelmed by choice overload, and they prey upon our dislike of losing out from loss aversion.

Example #1 - How the decoy effect influences your Tinder swipes

The decoy effect can affect how we behave when dating. We might be more likely to fall for somebody if we are exposed to a similar looking, but slightly less attractive, person beforehand.

Example #2 - How the decoy effect might influence politics

The decoy effect may have played a role in the 2000 US presidential election. Some psychologists view Ralph Nader as a “decoy” for the candidate he was most similar to: George W. Bush.

How to avoid it

To avoid the decoy effect, focus on only buying as much as you really need of something, and clarify ahead of time what characteristics are most important to you. People who are intuitive thinkers might be more prone to the decoy effect.

Related TDL articles

Asymmetrically Dominated Choices

The decoy effect is a type of asymmetrically dominated choice, which means the decoy is worse than the competitor in only some aspects, but worse than the target in all aspects. Read this article to learn more about the groundbreaking research discovering asymmetric dominance, and additional examples of how it impacts our day to day behavior.

Nudges

The decoy effect inherently relies on nudging: interventions that subconsciously steer our decisions towards some options and away from others. Read this article to discover more about the fundamental frameworks underlying nudging such as choice architecture, as well as how nudging can be used for the better—and for the worse.