Game, Set, Match: Getting Gamification Right

Funny story: I started using Duolingo, the language-learning app, exactly 427 days ago. My niece had begun French classes and I wanted to learn French, so we could converse without others intercepting us. She stopped her classes at school within 3 months. Meanwhile, I am stuck because I now have a 427-day streak on Duolingo and I cannot give that up. Actually, that’s not true; I can give it up, I just don’t want to.

At the other end of the room, my partner is busy playing FIFA 2021 on his PlayStation. I hear loud celebratory music. He opens a reward box. The screen becomes dark and then, amidst applause, out walks the latest player being added to his team. The drama of all of it is jarring and yet, addictive. I find myself waiting for him to open his weekly rewards.

When I question why he wastes time playing the game, he counters me by asking why that streak on Duolingo matters to me. I argue it’s different: I am learning a new language, thanks to that streak. But, deep down, I know he is right. We are both addicted to a form of engagement. His, a video game. Mine, gamification.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

What is gamification?

On any normal workday as an applied behavioral scientist, I would describe gamification as one of those annoying, trite buzzwords people throw around in meetings to appear cool and up-to-date with technological trends. It stands right up there, alongside “digital transformation,” “AI,” “machine learning,” and “the Metaverse.”

When someone mentions this G-word in response to a question on customer engagement, my conditioned response is to cringe. Why? Because when boardrooms talk about gamification, it is almost always as a high-level notion of some form of customer engagement, involving standard tools such as badges and leaderboards. In truth, gamification is a lot more nuanced than that—or, at least, it should be.

But today, I’m not speaking as a practitioner. Here, I am going to discuss gamification from a first-principles perspective, to explain why it is important and why it has to be done right. A “first-principles” approach would entail a more fundamental understanding of the underlying principles behind games and then applying them to a problem, rather than viewing gamification as a quick-fix solution.

Why do we play games?

Have you ever played Candy Crush? The colors, the drama, the sounds; getting sudden boosters, seeing yourself rise up the ranks on a leaderboard, progressing to harder levels—and then being told you have to wait 15 minutes to play the next game. Many psychological effects are at work here:

- Scarcity: Having limited attempts available makes the game feel more valuable than it really is. (So valuable that many people fork over their cash to regain access immediately.)

- Social Norms: It’s not just about performing well in the game, it’s about getting your friends to see that you are doing better than them.

- Unpredictability: What booster you will get, and when, is a surprise. This element of randomness has long been known by psychologists to be more habit-forming than predictable rewards.

Consider something more complex—for example, popular games like Fortnite or Animal Crossing. You don a new avatar and become a new person; you work towards goals like achieving new personal bests or upgrading your house; you encounter random rewards and form relationships with other players (whether real people or cute computerized animals). You can once again see many psychological effects at play here: self-image, intrinsic motivation, unpredictability, social norms, and so on.

These games function very differently, but they have a lot in common. They are both extremely engaging: even children can learn their rules and get absorbed in the gameplay. And they both rely heavily on user psychology and behavioral science to keep players interested. Game designers have an acute understanding of what gets users to engage, what actions feel intuitive, and what drives players to keep playing. They build this into the various mechanisms they use to make games fun.

From games to gamification

What, then, is gamification? I would say, from a first-principles perspective, gamification should be about bringing in the game designer’s mindset into designing any interface, be it a health app, an eCommerce app, a dating app, or a social network.

But a more formal definition available on the internet would be “adding game-like elements to a non-game environment.” I personally believe this distinction between the first-principles definition and the formal definition is very important. When we describe gamification as “adding game-like elements,” we are automatically boxing ourselves into a process where we identify what these game-like elements are and then force them to fit any non-game context, such as a website.

In most companies, the game mechanics people think of first are things like badges, leaderboards, and scratch cards. There are several frameworks, some very popular, that recommend this approach. For example, Octalysis identifies 8 principles and a few hundred techniques of gamification.2 They have, through years of playing games, identified “mechanisms” and offered them as a toolbox to interested people.

Here’s the problem: We then go on to force-fit these identified mechanisms into our own contexts, even when they’re not necessarily a good fit. (As the popularity of gamification has skyrocketed, this has led many companies to have awkward discussions like this.)

Don’t get me wrong: identifying basic mechanisms of gamification is a great starting point. My discomfort comes from the second part: people forcing these mechanisms into any and every context.

We often fail to ask ourselves:

- Do users want a badge for checking into your app every day?

- Do users want to be publicly ranked at #58,000 on some leaderboard? Will they really be inspired to purchase more to improve their standing?

- Do users want to deeply engage with your app on a daily basis?

Thinking like a game designer

To take a first-principles approach to gamification is to think like a game designer. Let’s say, for instance, we are a mapping company, and we depend heavily on users to add place listings to our maps. How should we go about encouraging them to do this more often?

The standard gamification approach might say: Let’s add a leaderboard! People like competing and seeing themselves on a leaderboard. The more places they add, the higher up they find themselves on the leaderboard.

But what if we take a game designer’s approach? In this case, we care less about nominally borrowing elements from games and more about whether or not our users will actually respond well to them. We care about whether a feature will realistically make an experience more fun and engaging for the user.

When we describe gamification as “adding game-like elements,” we are automatically boxing ourselves into a process where we identify what these game-like elements are and then force them to fit any non-game context … if we take a [first-principles approach], we care less about nominally borrowing elements from games and more about whether or not our users will actually respond well to them.

Do users care about adding places to a map? Do users want to be better at this action of adding places to a map? Probably not, which means that tools like badges might not be so effective.

Will they be motivated if they are seen on a leaderboard? Maybe, or maybe not.

Do users want to be seen on a leaderboard, where they compete with 100,000 other users and find themselves at the bottom? Would they be inspired to rise up this leaderboard? No.

But what if we put users on a smaller leaderboard, where they’re always relatively close to the top? Would this be more motivating? It’s very possible.

This line of thinking might lead us to conclude that a dynamic leaderboard, where we filter results in such a way that users always find themselves somewhere close to the top, is a good fit for our product. For instance, a user may languish at #58,000 rank on a standard leaderboard. But, competing with users who joined on the same day as him and living in the same residential area, they’re actually now ranked #300. Makes a world of difference, doesn’t it?

This is exactly what Duolingo does. Every week, you are sorted into a league and ranked on a leaderboard of only 30 people. These are the 30 people who started their Duolingo activity for the week on the same day, same hour, and at approximately at the same level. With this much smaller pool of competitors, there’s much less risk of getting discouraged—and much more incentive to work hard and climb to the top.

By actually considering the user experience and what users are likely to find motivating, we’ve bypassed gamified features that aren’t likely to be much help and arrived at one that might actually work in context.

Too much of a good thing? Understanding game refinement

Here’s another example of a first-principles approach to game thinking. Giving badges is a standard game mechanic; in eCommerce apps in Asia, for example, every few actions you take, you get a new badge. You can well imagine a product manager and designer hard at work thinking of ideas to improve engagement in their app and then deciding to give out badges. You log in every day, you get a badge. You buy something, you get a badge. You buy something every week for a month, you get another badge.

Sounds great, right? At virtually every turn, the user is given extra motivation to keep using the app. Here’s the problem: turns out, these badges lose their significance quite quickly.

An interesting paper by Huynh and Iida (2017) shares a very unusual insight into game mechanics.3 The authors use a metric called “game refinement,” which is based on the idea that every mechanic embedded in a game somehow “refines” the game, either adding to the user’s enjoyment or detracting from it. These game mechanics can be anything, like profile customization, new types of rewards, leaderboards, streaks, badges, etc.

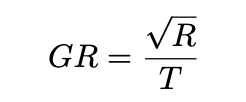

The game refinement theory gives a quantitative measure of how much an element “refines” the game it’s in. This is generally given by this equation:

Here, R = the average number of achievements or rewards, and T = the average number of efforts or tasks. How R and T are defined is different for every game mechanic.

Without going into the mathematics of the formula, let’s take a look at 2 of Duolingo’s mechanics: badges and streaks (the continuous number of days you complete a lesson in the app).

In the case of badges, the numerator (i.e. the reward) is the badges, and the denominator (i.e. the tasks) is the completed lessons that led to earning each badge. So with time, you are getting the same reward (a badge). As a result, your enjoyment of the badge decreases. Obtaining badges is an exciting activity, but doing so frequently will become boring. That explains why the attractiveness of badges decreases after a certain period.

In the case of streaks, it is slightly more complicated, because inherently, the longer the streak, the more prestige it carries. Someone on a 3-day streak might not care so much about losing it. Someone on a 427-day streak (like me) is desperate to keep it going—I would even pay to maintain my streak. (Duolingo lets you purchase “streak freezes” that protect your record, even if you technically miss a day.)

Hence, the definition of refinement must take into account the value of the streak at that moment in the formula. In this case, the numerator—the reward—increases with time, because the psychological weight the user places on this reward does too. Graphically, this is what the measured game refinement looks like for streaks and badges on Duolingo:

If you have used Duolingo as diligently as I have, you would notice that in the first month, you receive badges for every little thing you do. However, as you progress in the app, you receive fewer and fewer, until you’re hardly getting any new badges. This is because the Duolingo team is aware of the principles of game refinement (either explicitly or intuitively). As streaks come to matter more to you, it is less and less necessary to provide appeasements like badges to try to pique your interest—and there’s a greater risk that you might just start to find them annoying.

Please note that none of this has anything to do with whether or not Duolingo is an effective language-learning tool. Many have argued that it’s actually not so useful to help people acquire languages.4 But for the purpose of this article, I am focusing more on the app’s ability to engage users, rather than its ability to teach.

So, how do we do gamification right?

I am of the firm belief that gamification, like anything else in behavioral science, requires nuance. Treating it as a toolbox that has to be applied the same way in every context brings about many pitfalls. In the best case, it might give you a few engaged users. In the worst case, it will give you many annoyed users.

So, where should you start?

1. Clarify what you want to achieve, and what you want the UX to look like.

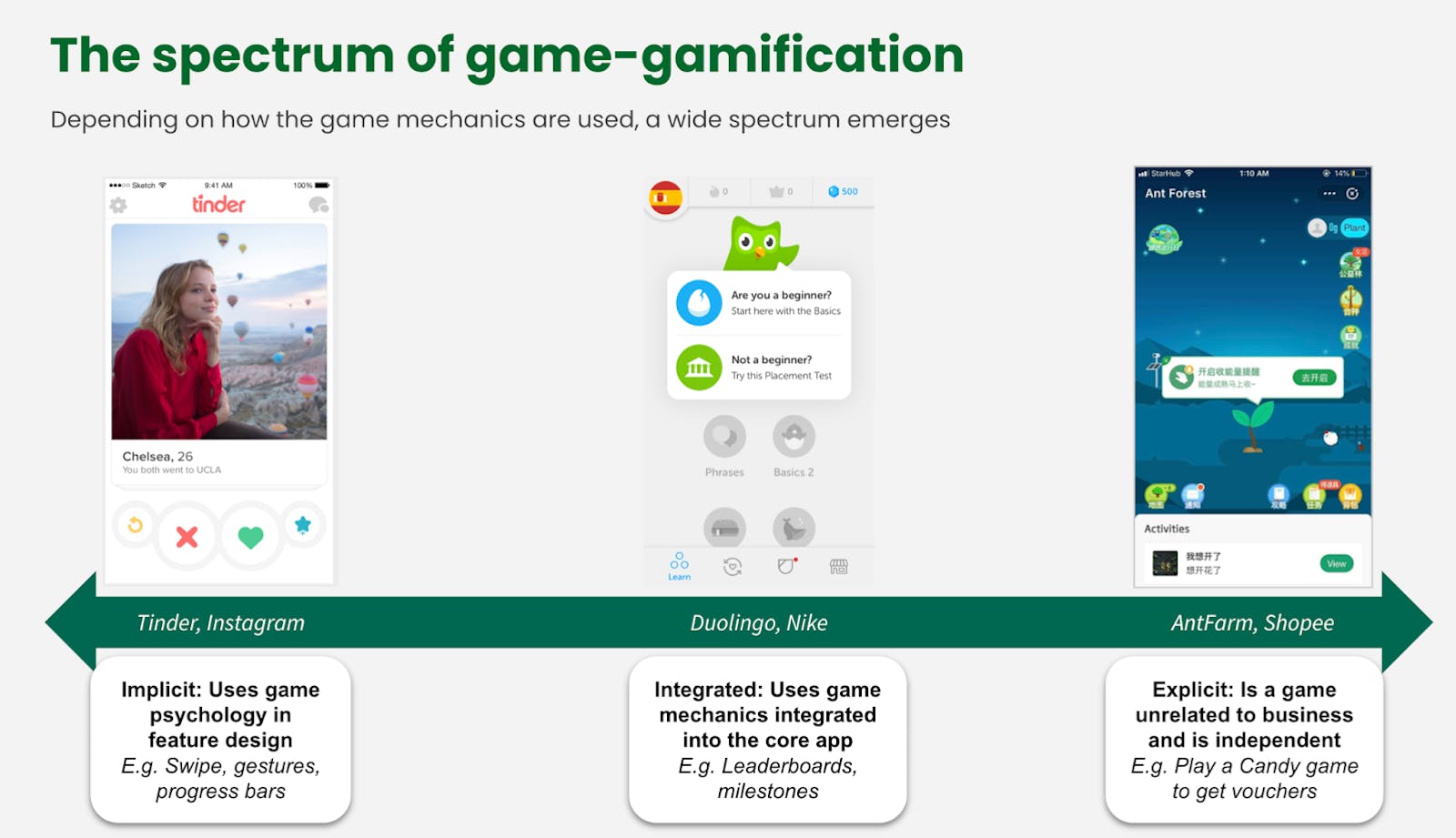

Should you gamify everything? Should you just use some game mechanics? It’s a spectrum. Decide where you want to lie on this spectrum.

If you are looking at implicit gamification, you are only looking for actions that make your app feel more natural to customers. For instance, take the action of swiping on a profile, like one does when using Tinder.

Contrast this with Duolingo, on the other hand, which uses an integrated mechanism: the entire app is designed around game mechanics. It is not a game per se, but it is structured like one.

Explicit gamification is when there is an actual game being played. For instance, consider the very famous Alipay Ant Forest, a feature that is separate from the rest of the app. Here, the user plays a game by growing a virtual tree, based on their different actions.

2. Think about what the user wants.

It is natural for us to start with business objectives. For example, how can I get users to engage more? How can I get users to check in every day? How can I get users to transact more? How can I get users to participate on my platform?

When you are asking these questions, also ask them from a user perspective. Does a user care about engaging more with my app? Does my app offer enough reason for someone to log in every day? Is my use case something that requires users to transact frequently? Does the user benefit from participating on my platform? What rewards does the user care about? Can I get away with just giving them a badge? If you’re not aligned on these, the users will be disengaged and lose interest in your game very fast.

3. Consider the ethics of your approach.

As in all things behavioral science, ethics are important in gamification. If you don’t do gamification well, you get disengaged users. If you do it too well, you get addicted users. Somewhere in between is the proper balance.

Robinhood, the stock investment app, is currently under the scanner for gamifying investments and misleading people into making wrong decisions about money using game mechanics.5 That’s a headline you don’t want to be a part of. This is where the user view comes in handy.

Final words

Gamification is nuanced. A toolbox approach is a great starting point, but may actually be a very boxed view of what games can really bring to the table. It is best not to treat gamification as a quick-fix solution for business problems, but to rather think of it as an opportunity to really understand human behavior, the way game designers do, and then apply that thinking in a way that’s pleasing to the user and also helpful to the business. Exactly how to go about being strategic about gamification deserves a whole different post.

Of course, it’s only thanks to gamification on Duolingo that I can say now with a French flair, “Tout est bien qui finit bien”—and hope to God I got that right.

References

- Glenday, J. (2013, December 9). Candy crush saga publisher delays IPO over fears game has become ‘Too successful’. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/candy-crush-publisher-delays-ipo-2013-12

- Octalysis: Complete Gamification framework – Yu-Kai Chou. (2021, March 8). Yu-kai Chou: Gamification & Behavioral Design. https://yukaichou.com/gamification-examples/octalysis-complete-gamification-framework

- Huynh, D., & Iida, H. (2017). An analysis of winning streak’s effects in language course of “Duolingo”. Asia-Pacific Journal of Information Technology & Multimedia, 06(02), 23-29. https://doi.org/10.17576/apjitm-2017-0602-03

- 500 days of Duolingo: What you can (and can’t) learn from a language app (Published 2019). (2021, March 17). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/04/smarter-living/500-days-of-duolingo-what-you-can-and-cant-

- Massa, A., & Robinson, E. (2021, February 2). Robinhood’s role in the ‘gamification’ of investing. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/robinhoods-role-in-the-gamification-of-investing/2021/02/02/fca1f562-6598-11eb-bab8-707f8769d785_story.html

About the Author

Preeti Kotamarthi

Preeti Kotamarthi is the Behavioral Science Lead at Grab, the leading ride-hailing and mobile payments app in South East Asia. She has set up the behavioral practice at the company, helping product and design teams understand customer behavior and build better products. She completed her Masters in Behavioral Science from the London School of Economics and her MBA in Marketing from FMS Delhi. With more than 6 years of experience in the consumer products space, she has worked in a range of functions, from strategy and marketing to consulting for startups, including co-founding a startup in the rural space in India. Her main interest lies in popularizing behavioral design and making it a part of the product conceptualization process.