TDL Perspectives: Becoming A Behavioral Scientist

This discussion between Sekoul Krastev, a managing director and co-founder of The Decision Lab, and Julian Hazell, an associate at TDL, addresses what applied behavioral scientists do, and what are some of the things that are needed to successfully become one. This conversation covers:

- What applied behavioral scientists actually do

- What the typical day looks like for an applied behavioral scientist

- What background is needed to enter (and succeed in) the field

- If graduate school is necessary to become an applied behavioral scientist

- Important trends in the field

- Important skills to learn outside of the classroom

- What skills prospective applied behavioral scientists often lack

- What is disrupting the field (and how to prepare for this disruption)

- What organizations an applied behavioral scientist can work for

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

Julian: Let’s start by asking what it means to be an applied behavioral scientist.

Sekoul: An applied behavioral scientist is someone who is in charge of reaching some level of understanding of how people are behaving in a system and then modifying that system to better accommodate those within it.

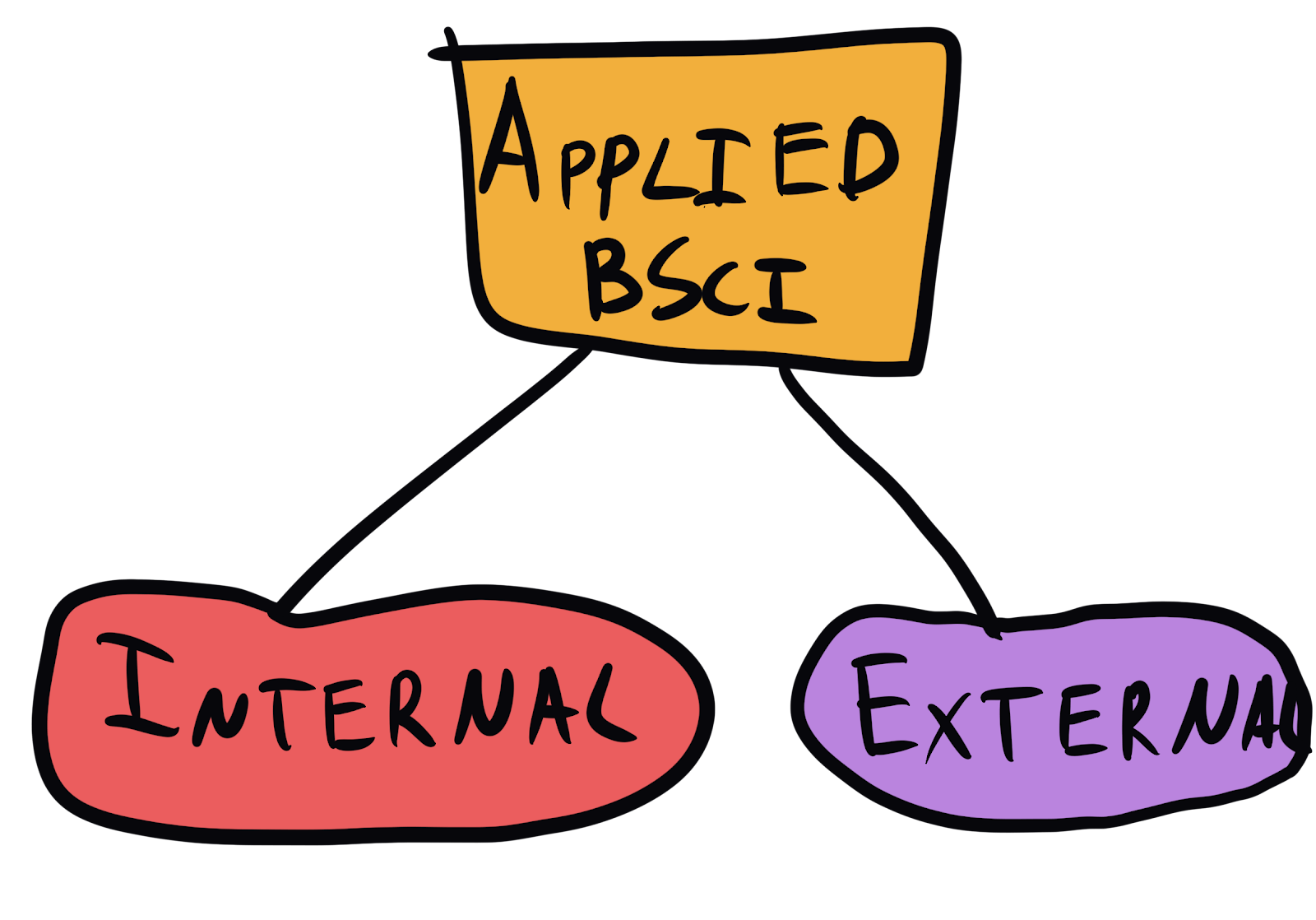

Typically, the work done by an applied behavioral scientist focuses on customers (external), or employees (internal).

A customer focused project would look at how customers are behaving in order to better understand them and potentially improve their outcomes.

The other case is when an applied behavioral scientist would look at how employees are behaving internally. They look not just at how employees are behaving, but what kinds of incentive structures might motivate them and how to change cultures, among other things.

An applied behavioral scientist is somebody who understands those types of systems of behaviors in order to improve them or to align behaviors with some sort of optimal outcome.

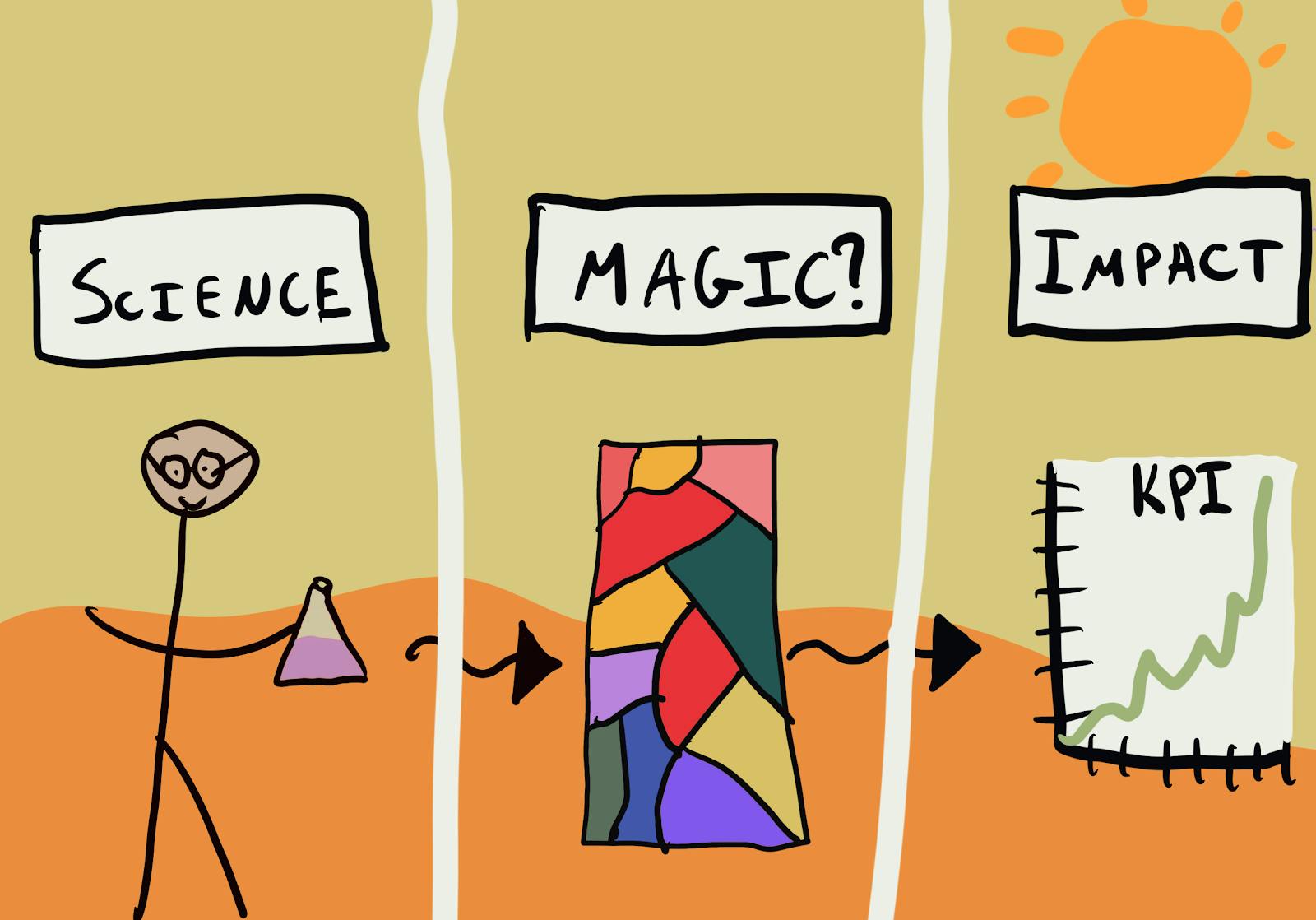

The reason they are called applied behavioral scientists is because, in order to accomplish these things, they’ll leverage insights from many different fields.

They will usually have a background in some aspect of behavioral science, meaning a sub-field such as psychology, neuroscience, or sociology, among others.

Someone from one of these fields will go through the process of taking all the insights they have from a theoretical level and figure out how to then apply them in a real-world setting — this is where the applied portion comes in.

An applied behavioral scientist takes techniques, such as creating surveys or running experiments, and adapts them in a way that answers useful questions in the context of customers and internal employees.

Julian: What is a typical workday for a behavioral scientist, let’s say in a large company?

Sekoul: A typical workday for an applied behavioral scientist depends on the kind of context that they work in. For example, if they work in an enterprise context where you have users, what they might do on a day-to-day basis is look at the particular Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that they’re in charge of changing in a certain direction.

Their day might start off in a standup meeting where they briefly discuss how the KPI is doing. For example, an applied behavioral scientist might talk about sales numbers, or engagement numbers, or number of downloads of a product, et cetera.

In that meeting, they also identify certain key goals, either in response to a KPI not moving into the direction they want them to, or maybe a more aspirational goal.

Then, they’ll work throughout the day to either dig into insights, to understand why things are happening and the way they’re happening — for example, why sales numbers might not be going up or why engagement might be going down.

Then, they’ll spend another part of their day designing interventions that are aiming to change that situation.

An applied behavioral scientist probably spends at least a third of their day in conversations with various teams in order to understand how a particular intervention they’ve designed might be implemented and tested in the real world, and then managing and coordinating that implementation and testing.

A final, smaller part would be to communicate all of that with senior stakeholders, depending on their level of seniority.

Julian: Okay, what about in a more niche environment, like a smaller company?

Sekoul: In a smaller company, an applied behavioral scientist — somebody who is maybe the only applied behavioral scientist on a team — might be asked to do different things, such as content production, or evangelizing behavioral science, helping to do user experience design, or helping to inform product design, among others.

There is a lot more variety of tasks throughout the day.

At the same time, the kind of data that they would be getting is typically less well-structured than in a large company. So they would end up with a lot more leeway in terms of designing the interventions, which usually means that they’d need a stronger emphasis on creativity and on being able to ideate and iterate.

Julian: Is there a right background for becoming an applied behavioral scientist?

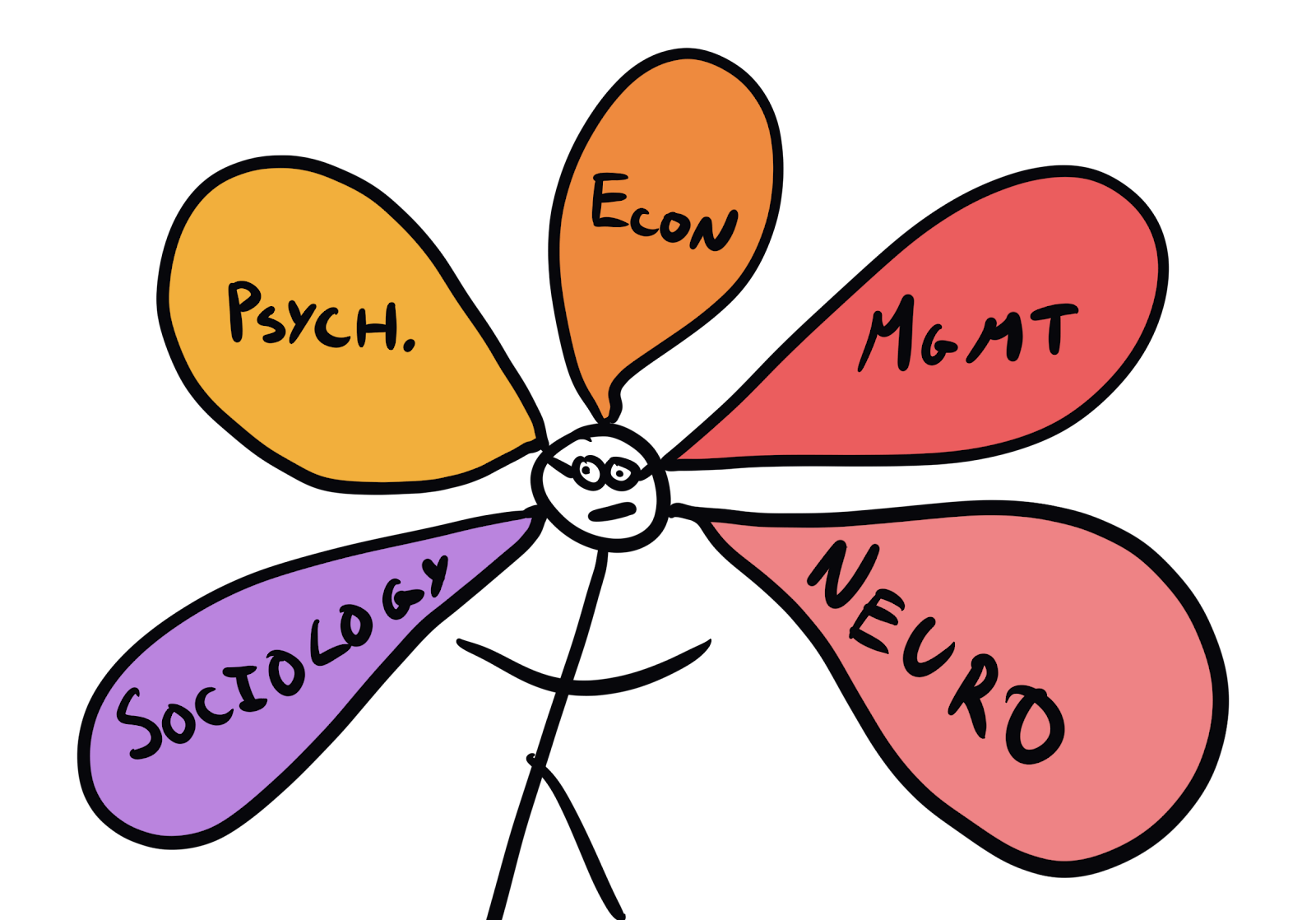

Sekoul: There are a variety of backgrounds that are useful in becoming an applied behavioral scientist. Ultimately, someone who is very good will learn about various fields that inform the kinds of work that they have to do at a company.

So backgrounds that can be useful are ones such as:

- Psychology

- Neuroscience

- Cognitive science

- Decision systems (which is a field within management)

- Anthropology

- Economics

- Sociology

Sekoul: That being said, people will usually come in with one of those fields with some sort of expertise and will then learn how to use that as a base in order to learn what the other fields can do to contribute to their work.

It’s very rare that someone will just use psychology, for example. They might start with a psychology background, but eventually will need to understand how people behave on a group level. So they’ll study some sociology, management, organizational behavior, or other fields to gain those necessary skills and insights.

In a nutshell, a good background is one that gives someone an idea of how people make decisions from the point of view of a single field, but also one that they can then leverage to pull insights from different fields.

Julian: How necessary is graduate school for pursuing this career?

Sekoul: Deciding whether to pursue graduate studies really depends on the kinds of skills that someone has built in their undergraduate program — a lot of people come out of undergrad with a pretty strong grasp of a particular field.

For example, somebody studying psychology might already have a lot of knowledge that they’ve picked up on various kinds of studies and theories. They might also have a strong background in statistics or things like programming.

So if someone comes in with those skills, even an undergraduate degree can be a very good starting point for becoming an applied behavioral scientist.

The AI Governance Challenge

That said, certain graduate programs, especially ones focused on research, can be very useful. It ultimately depends on what someone did in their undergraduate program and what the graduate program is.

Julian: Can you elaborate on the types of graduate programs relevant in this area?

Sekoul: There are two general types of graduate programs:

- Ones that are course focused.

- Ones that are research-focused.

A class-focused program will give you more knowledge within a specific field. It will usually focus on a subset of the fields. So, for example, if someone studied economics in undergraduate, they’ll then focus on something more granular, like behavioral economics.

A research-focused master’s or PhD program on the other hand is predominantly focused on producing some sort of research outputs. With one of these, one is essentially practicing the kinds of skills that would be useful in applied behavioral science, such as:

- Running experiments

- Learning about research methodologies

- Recruiting participants

- Incentivizing participants

- Checking if participants are doing the task that you set up in a good manner

- Creating pilots and then adjusting your task

- Doing power analyses

- Calculating what sample size you might need

- Creating engaging experiments

All those things are learned through practice. Graduate programs that focus on giving someone that kind of practice are very useful.

One caveat is that if someone spends too long in the graduate program, for example, a PhD, they might double down on a particular topic and then become a bit myopic when it comes to other topics.

It’s very important that when someone starts in applied behavioral science, they’re able to pull insights from different places. And that’s not something one typically learns as they’re doing something like a PhD. Usually, someone specializes more and more.

Julian: Are there any notable trends in the field of applied behavioral science that someone just getting started might be interested in?

Sekoul: One interesting trend is that people hiring for applied behavioral science positions a few years ago were really focused on the behavioral science portion of the equation.

Hiring managers essentially started by populating these nudge units or behavioral science teams with people who have a PhD in psychology or neuroscience.

And they assumed that these people, because they’ve studied these fields at a high level and had peer-reviewed papers, would be able to then take those skills and insights and transfer them into a real value add within the company in order to change, for example, sales numbers, or improve engagement in a product.

That has shifted with time. The idea that you can just take somebody with a PhD and get them to deliver real value on day one has really changed in the last few years.

And now there’s a trend towards looking for people who are essentially at the kind of meeting place between the more theoretical academic background and a more applied background.

So the optimal candidate shifted from being a PhD in neuroscience towards being someone who’s kind of a hybrid. For example, somebody with a master’s in neuroscience and a few years experiences in a business-focused position.

Julian: What about technical skills?

Another big trend is actually the overvaluation of technical skills in the field. It used to be important to hire somebody with very strong statistical skills or programming skills. In the real world, however, those kinds of skills don’t necessarily lend themselves to real value on day one.

Now, there’s still that kind of emphasis on some level of technical skills, but this has gone down with time. Instead, there’s a bigger emphasis on things like:

- Being able to follow certain design methodologies

- Being able to brainstorm

- Being able to work with others

And other skills on the softer side.

A lot of the initial behavioral science teams that were created didn’t perform as well as they could have, simply because they didn’t necessarily have the right balance of hard and soft skills. They overemphasized hard skills to the detriment of soft skills.

Julian: To expand on that, are there important skills that come from outside the classroom for someone looking to be an applied behavioral scientist?

Sekoul: The most important skill when one is applying behavioral science is the ability to tap into evidence, which splits off into two main categories:

Being able to read what’s already out there, and being able to run experiments to gather evidence yourself.

From a practical point of view, being able to read what’s out there means being able to read through papers like the ones on Google Scholar. Another way is by searching for a particular topic by opening up the most relevant papers and being able to read not only the abstracts, but also the methodology sections in order to understand what the key insights from the field are.

The other type is around testing by running experiments yourself. Once an experiment has been designed, one has to be able to validate it in the real world. One has to be able to:

- Design an experiment

- Code it

- Find an appropriately sized sample

- Run it

- Analyze the data

- Write it up

- Pull actual insights that one can then use to change an organization or a product

To develop those skills, what you might want to do is find some sort of behavior change goal that is considered interesting.

For example, say you might be very interested in fitness. In that case, you could focus on a subset of fitness. You could say, for example, that you want to develop better posture.

One good kind of activity to practice for being an applied behavioral scientist is a 3-step process:

- Go on Google Scholar

- Find different kinds of research talking about improving your posture from a behavior change perspective

- Design an experiment that tests out different kinds of interventions in order to see which one is most likely to improve posture over time

That process is something that you do nonstop in an applied behavioral science position. Finding an interesting and fun way to do that on the side while you’re still in school is probably the best kind of preparation you could do.

Julian: What is the most important part of the hiring process that applicants often lack?

Sekoul: A lot of people coming into the field are trained in the science part of applied behavioral science. They come in with many hard skills and a good familiarity with a particular field.

There’s usually a lack on the applied side, however, which is extremely important.

It’s pretty rare to find someone who is coming in with a balance of both science and applied experience. For most people, the lack of experience in going through the process of identifying a behavior change goal, looking for evidence, designing interventions, and then testing those interventions in the real world.

That process is something that not many people have gone through simply because the process itself is a combination of those technical academic skills and applied skills.

So, a lot of candidates will have experience on the technical side and will be able to read technical journals and examine evidence and design experiments and run them, but they won’t necessarily have an idea about how the results of those experiments might be implemented in the real world.

They won’t, for example, know about agile methodologies.

They may not know how to work with the UX designer, how to design features that are engaging to users, how to iterate through different versions of something.

The applied aspect — that connection to the real world, and ultimately the users — is what’s lacking in most candidates.

Julian: Could you discuss disruption in the field of applied behavioral science and how to be positioned against it?

Sekoul: There is a shift happening in applied behavioral science towards thinking about it as evidence-based design.

For some context, applied behavioral science is something that started off probably about `5 to 20 years ago. What happened was that the field of economics combined with psychology, forming what is known as behavioral economics. And this behavioral economics work started being more and more prominent with time, especially when it is applied in the organizational context.

People have focused more and more on this. They’ve taken insights from behavioral economics and tried to translate them into real-world change, which has had some success. And a lot of what behavioral science has done so far is based on insights from behavioral economics.

Julian: Are there pitfalls from focusing too much on the granular details?

Sekoul: One potential pitfall for people who are starting off in applied behavioral science is to focus too much on a particular field, and to think that the field is what’s delivering the value they’re seeking to deliver as an applied behavioral scientist.

And what evidence-based design means is less where the insights come from, and more about the ability to use the scientific method, to create interventions and then test them in the real world.

As the field becomes more agnostic to the bodies of knowledge that it might leverage, the skill set that’s needed from a person will be less reliant on a particular sub-field of behavioral science as well.

In order to respond to this trend, anyone looking to break into this field and stay in it for a long time should think about detaching from any particular fealties to neuroscience or psychology or sociology, for example, and think about what evidence-based approaches in design really look like.

Julian: What kind of organizations an applied behavioral scientist can work for?

Sekoul: The value of applied behavioral science is really dependent on the extent to which the behavior change goals can be shifted.

Some behaviors can only be shifted through systemic change. It’s important to identify whether the company offers an environment that lends itself well to the kinds of insights that behavioral science provides. Typically, what that means in the real world is essentially looking at companies where behavioral science is able to add value to the lives of users or staff inside.

A good test for that might be to think about what kinds of goals a company has and then to see, to what extent applying empathy, understanding users better and designing with their preferences, can be augmented through behavioral science.

Take banking, for example. There’s an enormous upside for somebody applying behavioral science in banking, because the kinds of decisions that go into an interaction with a bank are typically affected by a lack of information, a lack of understanding on the consumer side, a lack of resources in terms of time, in terms of the money, or a need to make certain decisions.

Behavioral science can alleviate or unblock a lot of the barriers that might be present for good decisions.

In other companies, however, the kinds of change that you would need could be systemic. And in those cases, an applied behavioral scientist might be more focused on things like marketing rather than actually helping consumers make better decisions.

And if you wish to apply behavioral science ethically, you should go towards companies that are able to actually improve the lives of those that they’re targeting, as opposed to just focusing on KPIs.

Julian: Okay, to conclude, what would you say are the 3 most important pieces of advice for becoming an applied behavioral scientist?

Sekoul: Number one: Think very early on about the kind of change that you’d actually want to see happen in your career.

More specifically, think about what kind of behavior change you actually want to create and what kinds of issues in the world matter to you. That will allow you to think more deeply about what fields would be relevant, what methodologies, even things like what statistical tasks or what software you might want to use. Everything should start with this idea of a cause or something in the world that you want to tackle in some way.

Number two: Once you have an idea of what your specific cause might be, think about all the practical implementations that are associated with it.

So for example, if you are interested in something like fitness, you might think about what particular tests are involved.

What types of interventions might be useful in raising the fitness level of someone? What are the most common pitfalls?

That will then allow you to think more critically about practical implementations of behavioral science principles, and to think about what kinds of tools and interventions you might want to design. And so within that category, actually getting your hands dirty and designing tools and testing them in the real world and something that should happen as early as possible, as often as possible, because it’s ultimately what you’d be doing on the job.

Number three: Stay field agnostic, and approach problems with an open mind.

If you’re looking to create behavior change in fitness, for example, just because you’ve studied psychology, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you should be tapping into insights from psychology to achieve your goal.

You could, for example, tap into insights from AI, you could use things like organizational behavior, etc. You could look at exercise science. There are many fields from which your insights might be pulled.

Think about what types of products have worked in the past. What types of features of them successful in different products is something that’s a very useful exercise.

Ultimately, a good applied behavioral scientist is somebody who is able to pull intervention ideas to open design opportunities in a wide variety of fields, pull them all together and then test them in the real world.

So becoming field agnostic, rather than being attached to a particular set of insights, is very important early on — and even more important later on.

Julian: Thank you for sharing your expertise, this has been really insightful and I hope that many future behavioral scientists will take this advice to heart.

About the Authors

Sekoul Krastev

Sekoul is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. A decision scientist with an MSc in Decision Neuroscience from McGill University, Sekoul’s work has been featured in peer-reviewed journals and has been presented at conferences around the world. Sekoul previously advised management on innovation and engagement strategy at The Boston Consulting Group as well as on online media strategy at Google. He has a deep interest in the applications of behavioral science to new technology and has published on these topics in places such as the Huffington Post and Strategy & Business.

Julian Hazell

Julian is passionate about understanding human behavior by analyzing the data behind the decisions that individuals make. He is also interested in communicating social science insights to the public, particularly at the intersection of behavioral science, microeconomics, and data science. Before joining The Decision Lab, he was an economics editor at Graphite Publications, a Montreal-based publication for creative and analytical thought. He has written about various economic topics ranging from carbon pricing to the impact of political institutions on economic performance. Julian graduated from McGill University with a Bachelor of Arts in Economics and Management.