Taking a Hard Look at Democracy

Introduction

Tom Spiegler, Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab, joins Nathan Collett to talk about what behavioral science can tell us about the 2020 U.S. election and the state of democracy more generally. Some of the themes we discuss include:

- The idea of a social contract: whether it is relevant and accurate given cutting-edge findings in behavioral science.

- Robust voting behaviour: how and why people actually can vote for themselves

- Cognitive diversity: the idea that we all think differently, and this influences the ways that we can come together to make group decisions.

- Our weaknesses to biases and frames, and how that influences our deliberative abilities

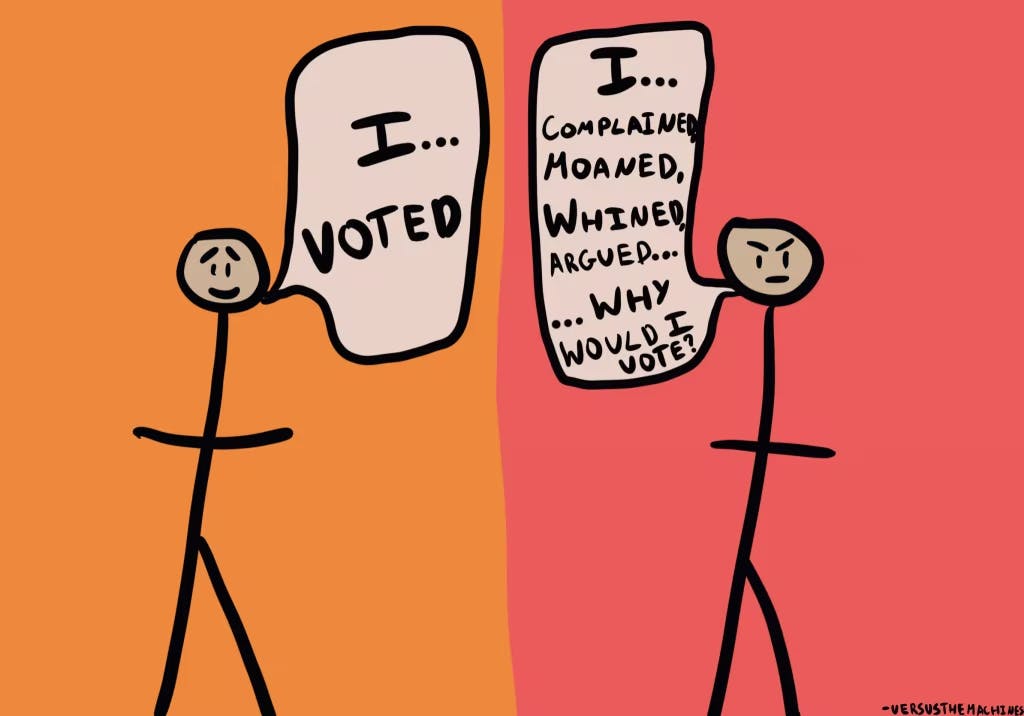

- The essence of democracy for a modern voter: the minimalism of voting and the power of collective action

- How different legal philosophies are based on differing notions of human agency

- Taxation reform, and how mindset shifts may be consequential for restoring trust in government

Discussion

Part One: Fundamental Issues and the Social Contract

Nathan: For the latest installment in our perspectives project, I’m sitting down with Tom Spiegler, one of the co-founders at TDL, and someone whose interests lie at the intersection of behavioral science and public policy.

Nathan: Tom, it’s been about a week since the U.S. election, arguably one of the biggest moments for democracy in the last couple of years. What are your initial thoughts?

Tom: What a wild ride. I think something that stood out to me—and something that has been becoming more troubling—is our inability as a society in the U.S. to come to any kind of collective agreement.

Tom: To that point—I saw an interesting statistic going into the election: that 50% or so of Republicans and Democrats thought that the election would be fair leading up to it. But after the election, now that it has become clear that Joe Biden won, that number jumped up to something like 75%-80% of Democrats who now think it was fair as opposed to something like 25% of Republicans.

Tom: Understanding human behavior is really fundamental to evaluating the relative strength of a democracy. The functioning of democracy relies on norms, conventions, and expectations of people’s behavior. And, as a result, numerous psychological processes contribute to the stability or instability of democracy.

Tom: To my point about a lack of collective agreement—I want to distinguish that from disagreement, which is a good thing. I think disagreement, political disagreement, in particular, is a form of engagement that is healthy and necessary in a democracy.

Tom: But the problem is that now we live in an era with multiple parallel news ecosystems. With the news media, you have Fox on one side, CNN and MSNBC on the other side, and social media algorithms pushing the more extreme views to you or views that you might already be inclined to agree with—you’re seeing that this has created bubbles of people living in totally different worlds.

Tom: So, we’re not really disagreeing with each other anymore, just having separate conversations. And I think that that’s worrying. I mean, there’s evidence in the behavioral science world that the strength with which you hold an opinion is proportionate to the extent to which you believe it’s shared by others. I think now with the media and social media landscape, that signal has become distorted and you see extreme views moving into the mainstream, legitimized by what you think is a majority endorsement.

Nathan: Yeah, that’s fascinating. I don’t think I’ve thought about it like that before but it is way harder now to tell what the majority of people are thinking just because, one, there’s so much information, and two, like you were saying, social media algorithms and also just kind of the structure of our social networks mean that we get information that isn’t a perfect representative sample of the rest of our society.

Nathan: We’re definitely going to come back to a couple of those themes but what I’d like to do first is take us through, starting at the fundamentals of democracy, working with the idea of a social contract, the idea of agreements and discussions. Then, moving into more ideas of cooperation and collective action. Finally, trying to bring out some behavioral science solutions to some of those current issues that we just talked about.

Nathan: Okay, so starting on part one, the idea of a social contract, the idea that we freely come together as perfectly autonomous individual beings, each with free will and the ability to think for ourselves, to act in our own best interests. Do you think behavioral science brings a challenge to that at all? Are any parts of the idea of autonomous free agents who are able to make decisions independent of any influence by other people, that is challenged by behavioral science, or do you think that’s still a solid paradigm for understanding things like the election?

Tom: I think one thing that behavioral science brings out is that a lot of what we do is shaped by the situation that we’re in. We have the perception of free will and autonomy and, to a certain extent, of course we are free creatures that make independent decisions—but, several experiments have shown just how much you can be influenced by the situation that you’re placed in. And I think, especially at the policy-making level, we should understand that a little bit better.

Tom: Underlying a lot of our laws—especially our criminal justice system—is this presupposition that people have really robust character traits that predict how they will act in the future, and explain why they acted in a given way in the past. But from behavioral science research, we know that there is a tendency to infer wrongly that actions are due to distinctive robust character traits rather than to aspects of the situation. I think lawmakers, policy-makers, even judges, need to be more aware of how people are subject to a `fundamental attribution error.’

Nathan: That’s really interesting. It reminds me of something that Cass Sunstein wrote a long time ago on moral heuristics and how we arrive at certain notions of justice, and other things that underlie legal structures, based on these assumptions that we have. I think one example had to do with punishment and whether we punish people, even when there’s no benefit to other people in the situation, from this criminal receiving punishment and whether we still think it’s a good thing just out of a sense of retribution. I think he was making the case that ultimately, we’re making these snap judgments about what’s right and wrong that are disconnected from the outcomes.

Tom: I’d agree with that. I think that there’s a good case to be made, based on behavioral science, for a to shift from a kind of retribution-based criminal justice system and legal system to a more rehabilitative one.

Nathan: In your experience in law school, how are you taught about the value of retributive versus distributive justice systems?

Tom: I think what marks a lot of the disagreement between the two camps is a difference in understanding human behavior. I think the retribution-based camp thinks very much in terms of character traits—if someone acts a certain way or commits a crime, it’s because they have a character trait that leads them to have a propensity to rob a store. The rehabilitative camp thinks that human action is more malleable. So, just because someone acts a certain way in one circumstance doesn’t mean that they’re that kind of person. Rather, a confluence of situational factors, among other things, caused that person to act in that way, and therefore we shouldn’t be locking this person up for 20 or so years at great expense to the taxpayer, when this person could be rehabilitated and contribute to society.

Nathan: Coming back to what you were saying earlier about how each one of our actions are affected by the people around us, regardless of whether traits to commit a crime are embedded or not within us, I think you get into a very complicated question of agency. When you commit a crime, is it your fault? If you’re in a situation for which we can label and define a lot of the inputs that cause or at least made it far more likely that you’d commit that kind of crime, is that still up to the individual to be wholly responsible?

Tom: I think that’s a hard question. I think it’s troubling to take the extreme position that you have no agency over your actions—we have to encourage responsibility-taking as a society. But, I do think on the other end, though, we do need to recognize that it’s a lot easier to make good decisions if you’re in a privileged position in society.

Tom: Oftentimes, what you see with those that end up in prison is that the deck was stacked against them. Sure, they made the ultimate decision to commit a crime, but there are a ton of situational factors that influence these things. Research shows there’s a real poverty-to-prison pipeline—and it’s not because those born into poverty have worse character traits but rather because of things like pervasive discrimination and aggressive policing of poor communities, among other things.

Tom: And then what happens is that once people get released from prison, often after 10, 15, 20 years, they are dropped back into the world with few skills and no support network. Combine that with employers’ reluctance to hire felons, banks being unwilling to loan money, and what you see is high-ish rates of recidivism. And then when that person commits another crime, those who would support longer prison terms will point to that and be like, “Look, this person was always the type of person who would commit a crime. Why are we letting them out at all or why are we even bothering trying to rehabilitate?”

Tom: To that point—there’s an interesting story about one of the professors who taught at my law school—Shon Hopwood. He grew up in Nebraska and he committed a number of bank robberies and went to prison when he was younger. I remember him talking on 60-Minutes, about how when he got out of jail in 2008, he had never seen an iPhone, never been on the Internet, and was computer illiterate. He was a rare success story but for the majority of ex-felons, how do we expect them to succeed under these circumstances?

Nathan: That’s super interesting. Okay, so pivoting a little bit. I want to talk a little bit about cognitive diversity. The way I’m using this word is just the pretty simple idea that we all have slightly different brains, slightly different ways of thinking about the world, but also, slightly different external attributes, too. It’s pretty universally recognized that we have physical differences among us, but I think there’s this idea that we also have varying levels of pretty intangible things like intelligence or creativity or persuasiveness or charisma. I found that the idea of cognitive diversity brings a bit of a challenge to, again, these traditional models of legal systems and democratic systems.

Nathan: Big question, but do you think that there is a challenge here where when you have people with varying levels of persuasive abilities, whether that’s based on their upbringing or just innate characteristics, does that variance influence the construction of group identity? If you have a group that’s supposed to come together to make this social contract out of their own deliberative action or out of everyone’s individual choices and their free will, when some people are by nature more persuasive or more well-liked or just able to process these ideas at a faster rate than other people, does this influence the creation of a social contract?

Tom: So what you’re saying is that because everyone has cognitive diversity, and some people are more persuasive, more intelligent, more charismatic, this affects group decision-making?

Nathan: What I’m suggesting is that the one person, one vote way of understanding democracy is that everyone will come to the voting booth and make a decision. However, when you think about when people are making their voting decision, you have to think about what factors are they taking in? They’re probably taking a lot of cues from whoever they decide are the experts and the people that are going to be those experts are likely to be persuasive people. Right?

Nathan: Do you think that ability to be persuasive would be random and distributed among the population or do you think that persuasive people will also tend to be the ones who have certain interests that other people don’t? For example, would more persuasive people tend to be more wealthy and therefore kind of favor the interests of a more elite class of citizens?

Tom: That’s an interesting point. I think you’re right. Western society, U.S. society in particular, clearly values traits like intelligence, persuasiveness, and charisma. Those people tend to rise to the top. And I think if you polled the interests of the 1% compared with the interests of the bottom 99%, you’d see some kind of difference there.

Tom: But I think that it is more complicated. Voters are more robust, or more complex than people think. One of the things that has encouraged me about the past four years or so is this resilience. I think if you asked me in 2016 what was the main issue that we need to deal with before all else, I would have said money in politics. Because at the time, I was worried that if the 1% can buy virtually unlimited amounts of TV ad time or social media ads—and if that’s enough to convince voters of whatever their point of view is— then we don’t really live in a democracy.

Nathan: A system driven by money.

Tom: Exactly. But that hasn’t actually been the case and when you look at a lot of the races that have happened this time around, in 2020, a lot of the very well-funded candidates didn’t end up winning. And actually, many of them didn’t even end up coming close to winning. I think that points to the voter being more complex than we might think, and our democracy being more robust than we might think. If nothing else, it’s definitely shown that voters are real people that think for themselves and are more complicated than just a demographic category. And I think that’s encouraging.

Nathan: Absolutely, that is a really good rejoinder there. I wonder if there are things we can do to amplify that diversity of information absorption if you’re thinking about them getting information from the neighbors and also experts and also social media? Is that a goal that we should pursue? Is that something we can alter or is it so robust that behavioral science interventions or other interventions can’t really do much to change that?

Tom: To change how people are getting their information?

Nathan: To change what information leads to political decision-making.

Tom: There needs to be an effort on the part of the social media companies and the media to do a better job of representing the whole country, because I do think that it’s relatively easy to only get fed a certain viewpoint.

Nathan: That makes me think of a bit of a manipulative way of providing information to someone. I mean, that’s a pretty well-known behavioral science intervention. Using social norms to tell everyone, oh, well, most people think this way, you should, too. Is that the kind of thing that should be stopped in politics? Should we be worried about people’s ability to harness behavioral science?

Tom: Yes. Especially when you’re using behavioral science at the government level for things like voting or convincing your constituents of anything, I think that we should be looking at how it’s being done. I think there’s a fine line between using behavioral science for good, say to increase voter engagement, and then to prey on these cognitive biases and vulnerabilities by leveraging confirmation bias or hindsight bias or all of these things that we know voters are susceptible to, like the bandwagon effect.

Tom: One of the things that I’ve started to look into, related to voting patterns and cognitive biases, is: does an over-emphasis on polls in the media affect voter behavior? The bandwagon effect, for example, is something that’s pretty well documented, which essentially is the concept that if something’s gaining popularity, people will look at that and be like, oh, I’m going to be for that, too, because I want to be on the winning team or I want to be supporting something that lots of other people support.

Tom: When you have a ton of polling, especially in the early stages—and I’m thinking here about the democratic primary elections earlier this year— so much of the focus is on who’s more electable, who do the polls favor, and so early on. I think there’s a possibility that voters look at that and it’s like, oh, I’m going to support this candidate who’s ahead, even though not a single real vote has been cast yet. And this is even worse if polls aren’t even accurately measuring public sentiment.

Tom: What we should be aiming for is an informed democracy and when we’re focusing on who’s ahead and who’s not, like a horse race type thing, we’re doing voters a real disservice and there’s a lot of psychological biases at play there that can have adverse effects.

Nathan: Yeah, this is super interesting. I think what I’m getting out of this thought is that those early interventions you were talking about, the kind of positive, non-partisan ones, are about making voting as easy as possible or at least facilitating the democratic process.

Tom: Right, how to increase turnout or engagement.

Nathan: Let’s bring in an interesting concept to make sense of this. We’re going to take Daniel Kahneman’s famous two systems approach. There is this intuitive, quick, automatic System 1, which is engaged in tasks like understanding someone else’s emotions. Things that you don’t have to think about, versus System 2, which would be like doing double-digit multiplication, let’s say 13 times seven. As soon as you have to do that problem, you’re in System 2. You’re doing deliberative work.

Nathan: I think one goal of an ideal democracy could be to get those positive interventions that you were talking about, those System 1 things, working. Get people to the booth. Get people thinking about democracy and doing democratic actions without thinking too hard about it. But then, and here is something new, then getting System 2 engaged once they’re making those decisions and not letting them get tripped up by confirmation bias or bandwagon effects. Having people change their mindset and go, “Oh, wait, I need to actually think about this. I need to process this in a way that is meaningful and isn’t just the first thing that comes to my mind.”

Part 2: Collective Action and Cognitive Restructuring

Nathan: So let’s get a bit more specific. When we’re thinking about democratic actions and things that are important to a voter, what does democracy feel like to an average person? When is someone doing a democratic act? When is someone actually participating in democracy in our modern, large-scale society?

Tom: That’s a good question and it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot. We’ve been hearing a lot about how our democracy in the U.S. is at risk. And maybe it is. But I think in a weird way, what I’ve seen—at least anecdotally, living in DC these past four years— is that our democracy is as strong as it’s ever been. I mean, over the past 4 years, I’ve seen so much political engagement, so many political marches, and political movements. So many younger political candidates unseating establishment incumbents despite having way less campaign money. And, speaking of campaign money—grassroots donations have been through the roof for both sides, with political sides being able to raise a lot of money from the average voter, in $16 increments, $20 increments, which I think shows a lot of engagement.

Tom: To your question what does democracy look like, to my mind, I think it is tuning in to what’s happening in the country. It’s getting out there and protesting or going to marches for what you believe in. It’s getting out there and making your voice heard, it’s voting. And looking at the state of things right now, you see all of this in abundance. This year we had a record-breaking voter turnout. President-Elect Biden got the most votes of any political candidate in the history of the country, and I think that’s a sign of a healthy democracy.

Nathan: Until the past couple of years, democracy sometimes feels like just kind of calling someone every four years to get them to come to a voting booth, checking a box and going home again. I think there are some real problems with that when you think about some of our more cutting-edge findings in behavioral science about expectations and how people understand cause and effect and how people are susceptible to suggestion. Just to take one, for example, I mean, when you have two things that are very distant in time from each other, it’s harder for people to understand that they are linked causally. Voting strikes me as something in this kind of structure, where you vote and you have your elected officials, but any sort of consequences of the vote doesn’t seem to land right away. Do you think there’s a way of improving that? Do you think that is a problem here?

Tom: I guess there are multiple parts to it. Just to tackle one aspect of this question—there’s the lag in time between voter action and the effect of whatever policies eventually do get implemented.

Tom: This disconnect is always an issue, and I think that is a real challenge looking into the future. If you look at the environment, for example, a lot of the roadblocks to environmental policy are that the benefits are less visible and more long-term, so a lot of politicians don’t feel like it’s politically beneficial for them to really die on that hill, to pass major legislation that’s going to maybe cost a lot of money in the short-term.

Tom: It’s not like the moment you pass a law, the earth gets a little bit cooler and everything gets better. The benefits are 10 years down the line, at least, and I think that’s one of the things that today’s politicians have to deal with. If the voter in the short-term sees their taxes go up because of new environmental legislation and then votes that politician out, that’s no good. I think that making the upside of long-term policy more salient for voters is really important. It’s something we’re going to have to get better at.

Tom: At the policy-level, the question is: how do we make the long-term benefits of a new law or regulation more salient? I don’t know whether we do that through economic policy, rewiring of the incentive structure or through interventions, which can make the future self more salient, or something else. I think that’s something that behavioral scientists in positions of power are going to have to grapple with and I think that public opinion and public willingness to tackle these issues now instead of just putting them off is an obstacle to good policy, and more generally, to good outcomes for all of society.

Nathan: Not that the two of us right now could just brainstorm the answers to all of these things, but I do have two things that may be interesting avenues to explore. One, more specific, and then one big broad one that we can end on. The first is that I was a little bit involved in local politics this past year. There was an election in British Columbia and one of the major figures in the party that ultimately won had to make a case for why they were calling a snap election because they called this election in the middle of a pandemic. People were quite upset because they felt that the election was unnecessary and dangerous. The politician’s argument went like this. He said, “We can’t make policies with a year left in our term that influence the next government. We can’t lock in our subsequent government, whoever you guys pick three years down the road, one year down the road, we can’t lock that government into certain commitments to whatever their agenda is just because it’s their job to govern when they’re in power.”

Nathan: The argument was, this politician was saying, we need an election because we need a mandate to institute this substantial economic reform plan to address long-term solutions to COVID-related economic issues and we can’t do that in the next year, we have to have a three-year mandate to do that. It made me think about how we could potentially give politicians a mandate to solve bigger issues that need long-term commitments. So this is my second, bigger idea. It is about trust and about continuation. I think what my local politician was getting at is that he has to protect the agency of this hypothetical future government, but also he needs to be able to act boldly to tackle the crises of our time. Somehow, there needs to be trust between the people in power, and between the different, opposed segments in society in order to fix these big problems.

Nathan: To elaborate a little on this, there needs to be two types of trust. Trust in a vertical sense means that we need to trust the people we put in power enough that they can implement policies that we may not appreciate right now, so long as they are really confident that they are in our interests in the long term. In a horizontal sense, there also needs to be trust. Political opponents need to believe that the enemy are good people, to the extent that they will not destroy the achievements of their predecessors, and fall into a trap of going back and forth, instead of working together to solve these big problems of collective action.

Part 3: Modern Solutions to Ancient Problems

Nathan: Going into our third section here, we can start where we left off and then move into some more concrete solutions. From what we were saying before, we were talking about problems, like environmental issues, and other problems that have long-term solutions that don’t pay dividends right away. How people have to agree on solutions to those and agree to take some small hits now to fix them later down the line. I’ll call that collective action, just kind of group behavior in the pursuit of group benefits down the line. I often compare it to a prisoners’ dilemma type of situation. If we all act selfishly right now, we’re going to end up with these suboptimal outcomes, but if we can all cooperate, then we get these good outcomes. What do we know from behavioral science, from policy, or just from just personal experience in a democracy, what works, what gets us to those collective outcomes, what do we need in terms of trust, in terms of community, in terms of just deliberating and discussing with one another?

Tom: People need to trust the system. If you have a system where policies that are supported by the vast majority of people, say 75% plus, are not being implemented, I think people lose faith in the collective and start to act more individualistically.

Tom: The current status quo creates this mindset of, like, if the government doesn’t have my back, then I need to have my back. Starting with Reagan onwards, there’s been less and less trust in the government, less and less faith that the government can do a good job, and government has become synonymous with bad or inefficient or ineffective. I don’t think that it needs to be that way. I don’t think that the government is inherently bad, but if the people that are running it are inefficient or ineffective or otherwise, then it’s going to lead to that impression.

Tom: So step one is to rebuild faith in the government. I mean, I think if you look at polling, government officials, people in congress, rank the lowest or second-lowest in terms of trust. I think below even lawyers, just above car salespeople. But if the government suddenly started passing policies that are favored by a large majority of Americans, aimed at improving the lives of the average American, you’d see that mindset shift.

Tom: One interesting thing that really shows how little faith Americans have in their government is the issue of taxes. Americans hate taxes, even more than people in other countries. And when you think about what a tax actually is, it’s paying money that then gets redistributed for social services or infrastructure, and the like.

Nathan: All of which are projects that hypothetically benefit society as a whole.

Tom: Yep. But people don’t feel good about giving money to the government, whereas people do feel good about giving money to a charity, like the Red Cross. Even though the Red Cross does a similar thing to what FEMA, for example, might do—and that to me is an interesting dichotomy that I think needs to be looked at.

Tom: One of the big conversations in the US is tax reform, tax reform, tax reform, because we need to raise more money in taxes. But before instituting a new tax, what about collecting all of the tax that is currently owed? When you look at the amount of tax that is owed to the government versus what is actually collected, there’s really a sizable gap there of billions of dollars. I think it’s impossible for the IRS to really police that. There are too many people in the country for that.

Tom: We need to get to a place where people want to pay taxes and it can be done if you look at some other social institutions that have similar projects. People want to give money to charity, people feel good about giving money to charity, but people don’t feel good about giving money to the government, even though the money is used for similar things.

Tom: I think making taxes easier to do, maybe making tax day a national holiday, maybe pre-filling the forms, maybe giving people some choice over how that tax money gets used. There are a number of ways in which compliance could be increased by changing the frame through which people understand taxation.

Nathan: Do you think that would make a difference, you think getting that information to them, telling them: here’s exactly how we spent your money? There is another example from my local political scene, about a recent tax that was super unpopular. It was called the School Tax because it was taxing people who owned very high-value property, but they named it after what it was going towards, which was support for the education system. In this case it still had a negative kind of affect associated with it. The frame didn’t seem to overcome that stigma. Is that information valuable? Do you think that shapes public opinion in a way that’s meaningful?

Tom: I keep going back to this, but people enjoy donating money to charities. There’s been a lot of behavioral science discussion over altruism and whether charitable behavior is motivated by altruism, and if so, what even is altruism? The research actually shows that there’s this kind of warm glow effect when you donate to charity. You feel good when you choose to give money away, so how do we get to a place where people get that warm glow when paying their taxes? That, to me, is an interesting problem to solve— and I do think it’s a very solvable one.

Tom: Maybe naming the tax after what it’s going towards isn’t descriptive enough or doesn’t do enough, but I think it’s at least a step in the right direction, even if it didn’t move the needle that much in your example above.

Tom: I think to sum up: trust in government is important because without faith in the collective, people act in an overly individualistic way, which leads to a tragedy of the commons situation. As in, if I think other people are going to be using this resource if I don’t, I’m going to exploit it, I’m going to take advantage of it because I can. If everyone thinks like that, we’re not going to be able to become sustainable or hit the environmental targets that we need to. I think it’s the government’s role to step in and change the incentives.

Nathan: All right. I think that’s an excellent place to end it. There’s a lot to think about there in terms of whose job it is to make these changes, whether it’s a question of people’s preferences being malleable enough to adopt that mindset or whether even like that reform could just happen easier than we think, where the people, just people taking a slightly different tone about taxation and making policy a collective effort, one that people really feel like they’re involved in, and making representative democracy into something that is properly and feels properly representative. I think behavioral science has to be at the heart of that challenge going forward and you’ve laid out a pretty convincing argument for that. That is all for now. Thanks a lot for joining me Tom, I found this to be a super insightful conversation.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

About the Authors

Tom Spiegler

Tom is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is interested in the intersection of decision-science and the law, with a focus on leveraging behavioral research to shape more effective public and legal policy. Tom graduated from Georgetown Law with honors. Prior to law school, Tom attended McGill University where he graduated with First Class Honors with majors in Philosophy and Psychology.

Nathan Collett

Nathan Collett studies decision-making and philosophy at McGill University. Experiences that inform his interdisciplinary mindset include a fellowship in the Research Group on Constitutional Studies, research at the Montreal Neurological Institute, a Harvard University architecture program, a fascination with modern physics, and several years as a technical director, program coordinator, and counselor at a youth-run summer camp on Gabriola Island. An upcoming academic project will focus on the political and philosophical consequences of emerging findings in behavioral science. He grew up in British Columbia, spending roughly equal time reading and exploring the outdoors, which ensured a lasting appreciation for nature. He prioritizes creativity, inclusion, sustainability, and integrity in all of his work.