The Mental Cost of Economic Insecurity

Is happiness for sale? Think of the gentle warmth of a hot chocolate on a snowy day, the exhilaration of a luxurious end-of-the-year getaway, or simply the contentment that comes with being financially secure. It's hard to deny the positive impact of material comforts on our mental health.

But is this a one-way street? Does economic insecurity take a toll on our well-being? And, if so, could poverty be a self-perpetuating cycle, where the negative psychological effects continue to worsen one’s financial situation?

Unpacking the Correlation

Let’s start with the first question. Contrary to the widely held belief of the 20th century, mental illnesses are no longer considered “diseases of affluence.” There are several pieces of evidence from both high and low-middle-income countries that prove there’s a positive correlation between poverty and mental illness.

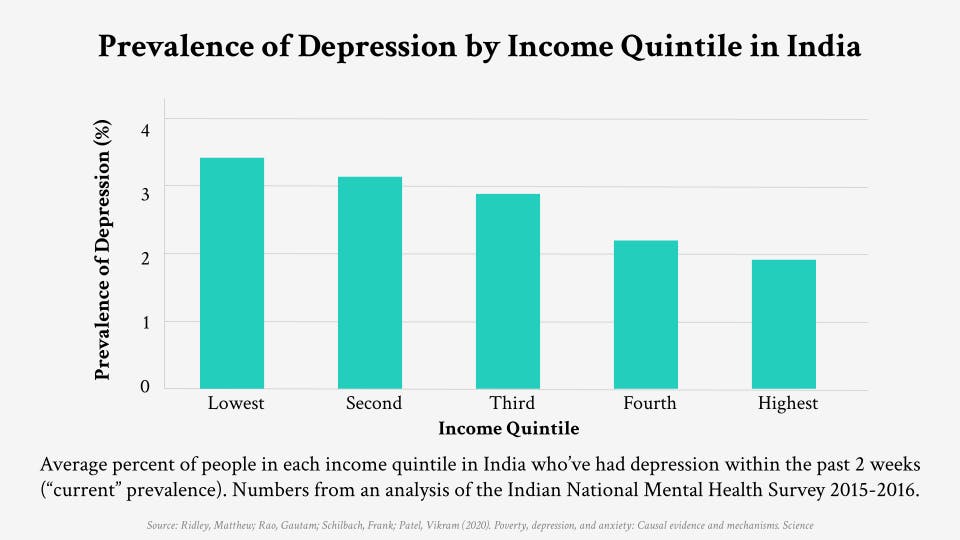

In a systematic review of 115 community-based studies, this correlation was observed in around three-quarters of them.1 In particular, participants with the lowest incomes in a community suffer 1.5 to 3 times more frequently from depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses than those with the highest incomes. To understand this more intuitively, look at the data from the Indian National Mental Health Survey below and notice the disparity between the lowest and highest income quantiles in depression.2

Even stronger evidence comes from a huge body of randomized controlled trials – not only proving the correlation between poverty and mental illness but the causation there, too. For example, Christian et al. showed that giving 22 dollars to participants in Indonesia decreased the suicide rate by a startling 18 percent when compared to the annual average.3 This was not the only case where an unconditional cash transfer – a financial payment made to individuals or households without any requirements attached – helped boost ratings of psychological well-being. McGuire et al. performed a meta-analysis of 37 studies of unconditional cash transfer in low and middle-income countries, spanning over 112,000 respondents.4 They found that, on average, receiving cash significantly improved participants’ mental health. This effect, although lessened, was still observed two years later, demonstrating a lasting positive impact.

In an extension of this work, Romero et al. included other economic interventions like conditional cash transfers (money given with certain requirements), asset transfers, housing vouchers, lottery wins, and free health insurance.5 On average, they found a small but positive effect on psychological well-being, with the largest effect being observed for unconditional cash transfers.

Together, these findings made a strong claim: there is a causal relationship between poverty and psychological well-being.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

The poverty trap

This scientific evidence validates that poverty can increase mental health issues. But is the effect so strong that these issues then, in turn, increase poverty, forming a poverty trap?

To explore this, we first need to understand what a poverty trap even is. In simple terms, this is a self-reinforcing mechanism that keeps either an individual or country in a state of poverty. However, a poverty trap doesn’t just entail the cycle itself. What’s key here is that a substantial financial lift is necessary to redirect one’s trajectory toward lasting stability.

So are the psychological effects of poverty enough to create this self-perpetuating cycle? Unfortunately, there is no straightforward answer. To explore this, Haushofer revisited a study in Kenya to examine how income influences psychological well-being and considered Lund et al.'s research in reverse: the effect of psychological well-being on income.6 From this comprehensive analysis, Haushofer concluded that a poverty trap specifically based on depression is unlikely. However, when Haushofer previously delved into research by Oswald, Proto, and Sgroi, he discovered a different conclusion regarding the impact of happiness, suggesting a more complex interplay between financial status and various aspects of psychological well-being.7

In short, research diving into how mental health impacts poverty challenges the idea of a straightforward poverty trap, but still underscores the critical link between mind and money.

The cost is more than mental health

While the psychological poverty trap remains a puzzle to us, the potential bidirectional effect between poverty and psychological well-being should draw our attention. Unfortunately, there is emerging evidence revealing that the mental impact of poverty goes beyond emotional well-being.

Recent work in behavioral science suggests that poverty may reinforce itself by influencing financial decision-making processes like savings, consumption, and investment. One way this might happen could be through taxing cognitive bandwidth. For example, Mani et al. experimentally prompted thoughts about financial situations among participants and found that this reduced cognitive performance among poor participants but not well-off participants.8 Later, the researchers examined the cognitive bandwidth of farmers over the planting cycle. They noticed that the same farmers exhibited weaker cognitive performance before the harvest when poor, as compared with after harvest when rich. By reducing the cognitive bandwidth available to engage in life’s activities, people may feel less joyful or satisfied from any given level of consumption.

Beyond Money

Is happiness for sale? The short answer is that there isn’t a single narrative. The intricate relationship between poverty and psychological well-being represents the multifaceted nature of social welfare. For development practitioners leveraging behavioral science as a tool, this is a clear sign we should take a more holistic approach, incorporating psychological support and mental health interventions into economic development programs. This integration is crucial for designing solutions that are truly transformative, capable of breaking the complex cycle of poverty and fostering a lasting impact on both economic and psychological well-being. Only by recognizing and addressing these interconnected facets can we hope for happiness to be on sale for everyone.

References

- Lund, C., Breen, A., Flisher, A.J., Kakuma, R., Corrigall, J., Joska, J.A., Swartz, L., & Patel, V. (2010). Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 71(3), 517-528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027.

- Ridley, M., et al. (2020). Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms. Science, 370, eaay0214. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay0214

- Christian, C., Hensel, L., & Roth, C. (2018, July 31). Income shocks and suicides: Causal evidence from Indonesia. Retrieved from http://barrett.dyson.cornell.edu/NEUDC/paper_338.pdf

- McGuire, J., Kaiser, C., & Bach-Mortensen, A. M. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of cash transfers on subjective well-being and mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(3), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01252-z

- Romero, J., Esopo, K., McGuire, J., & Haushofer, J. (n.d.). The effect of economic transfers on psychological well-being and mental health. Retrieved from https://haushofer.ne.su.se/publications/Romero_et_al_Metaanalysis_2021.pdf

- Haushofer, J., & Salicath, D. (2023). The psychology of poverty: Where do we stand? (NBER Working Paper No. 31977). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31977

- Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2014). On the psychology of poverty. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 127-148. American Economic Association.

- Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976-980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

About the Author

Xingyan Lin

Xingyan Lin is a Senior Associate at The Decision Lab. She holds a Master’s in Development Practice from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Bachelor’s in Public Policy. She believes in the incredible power of human cognitive behavior to change the world for the better.