Ting Jiang: Hacking Health And Savings

Art by versusthemachines

For daily habits in the interest of health [and] happiness, let’s say that they tend to be system one—we can use a nudge. But for decisions that are related to unique preferences—identity, infrequent and key decisions in one’s life—maybe we still use nudge, but the right type of paternalism is not to nudge them not to think about them, without their own awareness, but actually nudging them to deliberate on them as much and as long as needed

Intro

In today’s episode, we are joined by Ting Jiang, Principal at Center for Advanced Hindsight, a behavioral science lab at Duke University, researching and designing interventions and products for behavioral change. Ting is an experimental economist by training, a philosopher at heart and a psychologist in action. Previously, she was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, conducting research on diagnostic tools for social norms and interventions for norm change. For the past two years, a substantial portion of her time has been dedicated to conducting field studies and designing product solutions to help low-income Kenyans improve their financial and health decisions.

The conversation continues

TDL is a socially conscious consulting firm. Our mission is to translate insights from behavioral research into practical, scalable solutions—ones that create better outcomes for everyone.

In this episode, we discuss:

- How a dice game that Ting designed on cheating got her into behavioral science*

- The calendar that was redesigned to promote financial health

- More healthy living projects: The Hidden Gym project and Nappiness

- Evidence versus intuition in designing interventions: Why the biggest challenge is trusting the evidence, rather than our own intuitions

- How to foster a culture that embraces risk-taking and experimentation

- Understanding the mechanisms that drive effects is the key to “good” research

- Why businesses must start prioritizing consumer well-being

- From fin-tech to behavioral tech: optimizing automation and engagement for products/services

- How to become an applied behavioral scientist

Key Quotes

Sometimes we feel good about cheating

“We don’t like to cheat when other people know we’re cheating, so this game creates an opportunity for you to lie without the other person knowing that you are lying. If I ask you to play this game for, let’s say, 15 times, I can actually infer statistically whether it’s likely or not that you have been lying, just because you can’t be guessing the good side all of the time. And the other is yes, we are tempted to cheat a lot of the times, and depending on the context we might feel good or bad about our cheating”

The calendar that hacked savings

“We had asked to plan their saving date on the calendar and we asked them to set a goal, a very simple goal setting and tracking feature, and all of these have shown quite substantial effects, [this means] that the intention to save was probably there but that people were bad at following through their intention. And with the calendar, which is hanging in their home environment every day, reminding them not just the fact that they want to save but also how exactly, when exactly, and what’s the tangible consequence that could come out of it—we were able to promote saving.”

A phased-out donor contribution model teaches recipients how to save

“And the key feature for Mbrella is that it’s going to be a graduation model where the donors are going to chip in less and less over time, co-funding for their health insurance which is only $60 a year. So they started with the Kenya recipient saving for only $1 a month and $4 coming from the donors, but over six years we’re going to phase this out in terms of donors contribution and the recipient will save more and more. And how do we get them to save more and more? It’s through some of these behavioral interventions that we’ll do for them, one of them being a financial decision board game where they experience health shocks, they learn how to cut down unnecessary expenses, save more for healthcare.”

Believing in data feels counter-intuitive

“I think the biggest challenge I’ve encountered is the human tendency to believe in intuitions rather than evidence, which is related to our own biases of overconfidence and confirmation bias. And I had to deal with this challenge not only when I communicate and work with our partners, but also among our internal team and even myself.

Believing in data or evidence rather than intuitions is counter-intuitive, by definition, and very difficult to do because our thinking habits oftentimes are very automatic and judging by evidence is not something that we do instinctively and requires more deliberative efforts.”

Using evidence to change our priors

“So having those moments where we pause and say, “What is really the evidence?” And once we have the evidence, digest [it] and say, “Okay, it’s time that we change our prior.”

The right way to nudge preferences and identity

“For daily habits in the interest of health [and] happiness, let’s say that they tend to be system one—we can use a nudge. But for decisions that are related to unique preferences—identity, infrequent and key decisions in one’s life—maybe we still use nudge, but the right type of paternalism is not to nudge them not to think about them, without their own awareness, but actually nudging them to deliberate on them as much and as long as needed.”

With effective nudges, we can all become philosophers

“And I would even speculate that in 10 years we will all become philosophers, we would finally have time to reflect on the meaning of life because of all the trivial decisions not only tackled more effectively via nudges, but taken out of our choice set to liberate us to think for ourselves in those key decisions. And then we would behave more and more in line with our true identity and unique preferences, if we apply paternalism in the right way. And as you said, it’s key to think about how do we identify decisions where we should nudge and in what way do we nudge, and I find Kahneman’s model of system one and system two actually very helpful in thinking about this question.”

Scaling up, cost-effectively

“Because we [at the Center for Advanced Hindsight] don’t rely on our own intuitions of the effectiveness of the solutions that we propose, we only scale up those that we have evidence of its effectiveness.”

The mechanism that drives the effect matters

“Good research is research that allows you to understand the mechanism of what drives the effect, so if you know A works better than B you don’t just know it because it works, but also because it’s addressing self-control with reward substitution or increasing attention via highlighting supportive norms. And in those cases you can generalize this to any context that is actually similar to this, knowing better the mechanism.”

Shifting business gears: Taking into account consumers well-being

“It’s not a competition at this point, but I think soon enough if we apply [behavioral science] to the public policy long enough and substantially enough, we will get to the point that consumers are going to support the businesses with more aligned interests than not.

I think for smart businesses who want to succeed in the long run it would be wise to shift gears in to also taking into account consumers’ wellbeing, happiness, and health in the calculation.”

Fintech to behavioral tech:

“So like the concept of fin-tech, which refers to new technologies that seem to improve and automate financial services, behavioral tech, on the other hand, refers to new technologies that improve and automates human participation and behavioral uptake in products, services, and programs such as new tech that would improve behavioral adherence to medications, diet, lifestyle changes and health. And I think systematic application of behavioral tech could be the next breakthrough of innovation, not just in healthcare or public sectors, but also in [the] kinds of products that we would create [and] invent, for consumers.”

Articles, books and podcasts discussed in the episode:

- Cheating in mind games: The subtlety of rules matter (Dice game on cheating) (Jiang, 2013)

- Mbrella: Promoting well-being via behavioral science informed tech and products

- Shapa: Weight loss app with a numberless scale

- M-TIBA: Mobile health savings wallet for Kenyans

- Center for Advanced Hindsight newsletter

Ting’s Work

- Can Trust Facilitate Bribery: Experimental Evidence from China, Italy, Japan and the Netherlands (article published in the Journal for Social Cognition)

- Cheating in Mind Games: The Subtlety of Rules Matters (article published in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization)

- Gamification as a life-saving medicine (Games for Change, Ting Jiang, 2019)

- Games and gamification, , Literature Review (Center for Advanced Hindsight)

- Habit change, Literature Review (Center for Advanced Hindsight)

- A binary variant of the mind game

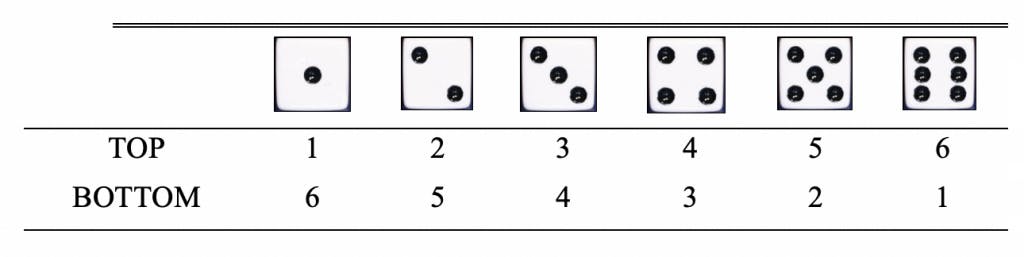

*Clarification on the Mind Game: In this game, instead of getting your earnings based on the dice outcome, i.e., the number of dots on the top side, you would choose the top or the bottom side of of the dice that would count for your final earnings, before you roll the dice. You make this choice in your head, without sharing or report it with others—this allows you to cheat by misreporting the side after seeing the dice outcome, without ever fearing any repercussions. For instance, if you see that the top side has 1 dot, and you chose “top” before you saw the dice outcome, you are still able to lie and report that you actually chose the “bottom” side, which would result in an earning of 6 instead. As shown in the table below, cheating gains vary from 5 points (1 vs. 6), 3 points (2 vs. 5) to 1 point (3 vs. 4).

Table 1: Earning points corresponding to “Top” or “Bottom” side of the dice.

Transcript

Jakob: Thank you so much for joining us, Ting, it is great to have you today. We would like to speak with you about the newest innovations in behavioral science and what trends you foresee in the coming future. But before jumping into that I think a lot of people would love to first understand how you came to work on behavioral science. The Center For Advanced Hindsight is arguably the think tank for applied behavioral science, started by famous and groundbreaking professor and behavioral economist Dan Ariely. The initially small lab housed at Duke University has evolved into a strong team of over 100 behavioral researchers as well as thousands of avid followers. You are one of the most senior people at the lab and have worked closely with Professor Ariely for a while, can you tell our listeners what motivated you to get into behavioral science and how you went about it?

Ting: Okay Jakob. So I came to work on behavioral science because of Dan. I met Dan when I was doing my PhD in economics in the Netherlands and I’m not sure what kind of good deeds I did in my past life, I was given a full hour meeting Dan in my office, and I was very thrilled to show him a game that I created to capture cheating. So I don’t know if we have time, if I could share how this game works, because it can help you understand the rest of the story.

Jakob: Absolutely, please go ahead, Ting.

Ting: Okay. So Jakob, imagine that I tell you look at this six sided dice, and when it lands it has a top and bottom side, usually the number of dots on the top side counts as the dice outcome. But in this game you have to choose top or bottom in your mind before I roll the dice, and after the dice roll you tell me which side you chose in your mind and the if the side you chose has more than three dots let’s say that you will be invited to write a book with Dan next year. Now, keep in mind that any 2 sides of a 6 sided dice add up to 7: 6 vs 1, 5 vs. 2, 4 vs. 3, so you always have a side that has numbers bigger than 3 and the other less or equal to 3. So if you see the dice outcome on the top side is 1 you know the other side the bottom side is 6, if the top side is 2, the bottom side is 5, if the top side is 3, the other side is 4, and vice versa.

So, as you see, the beauty of this game is that you only need a dice and people can lie at ease in front of you without leaving any trace of evidence. Of course here you didn’t lie, but supposing you lied I wouldn’t know, right, whether you lied to me or not. So Dan was very impressed by the game back then and told me that he forgot his recorder, otherwise he would have done it also with me on his podcast, Arming The Donkeys. So I was really blown away by that, a giant showing such encouragement towards … back then I was just a graduate student.

Ting: So, not long after, my supervisor actually told me that he met Dan at a conference organized by Uri Gneezy and then had my game on his iPad and he already started collecting cheating data all over the world. So I was again impressed, a professor with a speed of an entrepreneur, and lastly I missed the conference because of a VISA problem and I emailed quite few people to check out my poster and guess what? Dan was one of them, but he was the only person who sent me a photo of my supervisor, Jan Porters, standing in front of my poster, presenting it on my behalf, with a glass of wine. And the email was titled Evidence, so I was really impressed by his extraordinary thoughtfulness.

Ting: So those impressions actually resonated in the bottom of my heart for years until some seven, eight years later that he invited me to visit the lab at Durham, and I couldn’t help making an offer to him to work for him. So there I made a shift from experimental economics to behavioral science and that’s how I came to work on behavioral science.

Jakob: Fantastic, what a wonderful story, Ting. Let me just go back for a second to the game. So I understand that the whole point of the game is to kind of show that most of us are inclined to, I guess, lie, or cheat, when the opportunity arises. Can you explain the purpose of the game a little bit more? I’m very curious about that.

Ting: Right. So we don’t like to cheat when other people know we’re cheating, so this game creates an opportunity for you to lie without the other person knowing that you are lying, first of all. But still, if I ask you to play this game for, let’s say, 15 times, I can actually infer statistically whether it’s likely or not that you have been lying, just because you can’t be guessing the right side all of the time. And the other is yes, we are tempted to cheat a lot of the times, and depending on the context we might feel good or bad about our cheating, but in this particular game we for example found … so two opposite sides of the dice always add up to seven, so one versus six, two versus five, three versus four, and if I would pay you according to the dice outcome, if it’s six I pay you six Euros, if it’s one I pay you one Euro, or dollars, you could, when it is one and six, if you got the unlucky side when you lied you got five Euros more. But if it’s three versus four you got only an improvement of one, and two and five an improvement of three dollars.

Ting: So the question is under which numbers do people actually lie the most? Is it one versus six where you get the most gains by lying, or three to four, the least, or the middle? Do you have a guess?

Jakob: Well I’m assuming it’s probably where they can get the most out of it.

Ting: So, no, so it turns out to be two to five.

Jakob: Okay.

Ting: So people actually feel bad, if it’s one to six it might be too obvious. Like okay, right, it’s by the gain of five and maybe because people would expect them to cheat there they want to actually show honesty. But when it is three and four maybe it is just too little gain to be worth it, the moral cost. So it turns out that we find a pattern of peaking at two and five.

Jakob: Very very interesting.

Ting: So, again … yeah.

Jakob: Okay, well no, that’s fantastic, thank you for clarifying that a little bit, I think that makes a lot of sense now. Great, so Ting, I’m going to move onto our next question which is we would like to find out what are some of the more exciting projects that you’re currently working on, can you walk our listeners through some of them?

Ting: Sure. So as the global arm of our center we started in Africa three years ago to promote saving for health with some very generous sponsorship from umhlanga Institute whose mission is to improve a digital age for innovation in global health. And [inaudible 00:08:47] that game changing innovations are needed to really make an impact and puts a lot of faith in the discipline of behavioral science in our team. So we have designed and tested dozens of interventions in the past few years and getting close to, I would say, a more holistic intervention program to effective behavioral change of the poor. But I must say a lot of the messaging tests that we did was counter intuitive in the results, it was just results that we didn’t expect, but I was really excited when we had a few interventions of achieving the effect size of doubling savings with quite long lasting effects.

Ting: Maybe let me give one example, which was a calendar that we gave away to low income savers, and we had used the control calendar which was what the PharmAccess Foundation originally used as a giveaway with brand images. But we also, for some, changed or replaced the brand images with inspiring non-changing stories on it. So what did I mean? So through some qualitative findings we found that men typically don’t perceive themselves as savers, women do, but in the story we had Joseph, who’s a guy living in Kibera, who ended up saving and when the daughter, Olivia, was sick, they were able to take the daughter to the clinic and the doctor said to Joseph, “Wow, lucky that you are here earlier because it would have cost you more if you delayed a visit.” And when they went back home that night the wife told Joseph that, “I’m so proud of you, that you are able to take care of our daughter, Olivia.”

Ting: So such a story, which is … again, we did interact with the users more than the control calendar, but it was able to improve savings by a lot. So the control calendar we end up finding 0% of people saving in the first three months, but with the calendar we had close to 8% who save, and some with multiple times. Then with some other calendars we had asked to plan their saving date on the calendar and we asked them to set a goal, a very simple goal setting and tracking feature, and all of these have shown quite substantial effects, which meant that the intention to save was probably there but that people were bad at following through their intention. And with the calendar which is hanging in their home environment every day, reminding them not just the fact that they want to save but also how exactly, when exactly, and what’s the tangible consequence that could come out of it or that other people are also saving, in this case Joseph, and they might over-interpret how many Josephs there are in their community, we were able to promote saving. So that was quite an exciting result for us.

Ting: And the other exciting project is Mbrella, which is new charitable giving startup to match donors and recipients, which we also call Uber for healthcare. And the key feature for Mbrella is that it’s going to be a graduation model where the donors are going to chip in less and less over time, co-funding for their health insurance which is only $60 a year. So they started with the Kenya recipient saving for only $1 a month and $4 coming from the donors, but over six years we’re going to phase this out in terms of donors contribution and the recipient will save more and more. And how do we get them to save more and more? It’s through some of these behavioral interventions that we’ll do for them, one of them being a financial decision board game where they experience health shocks, they learn how to cut down unnecessary expenses, save more for healthcare. Through experiential learning and more emotion based learnings as well as concrete behavioral habits that they want to acquire moving beyond the game.

Ting: And let me say maybe one more project we’re doing in Europe with an insurance company to promote healthy living, so getting people to exercise more, healthy diet, and working with their talented app development team, Actify. We have, for instance, launched a new concept called Hidden Gym where users are given inspirations to take steps in unexpected cases, like walking stairs for multiple times a day instead of really going to the gym. So we found out that one of the core barriers for not exercising enough is that people typically don’t have enough time and Hidden Gyms are easy to do without spending more time, but they’re also more enjoyable and before you know it you actually have done your exercise amount for your day. So this is something quite exciting for us because we have found preliminary evidence on how more engaging it is.

Ting: And for the coming year the team will be focusing on also healthy living interventions in the workplace and there I’m particularly excited about behavioral change interventions around resting, which is less obvious than exercise and diet, such as 20 minutes midday napping or meditation. Why napping? First, health benefits on heart, health, and also mood. Second, while most people have the intention to exercise more and eat better, fewer actually want to nap, because they associate napping with the elderly and children and the weak, so the room for change is even better. And our [inaudible 00:15:47] partner team actually has a cute name for this campaign called Nappiness, so to increase happiness and health via Nappiness, that’s also quite exciting in 2019.

Jakob: Such powerful examples, thank you so much for sharing those, Ting. I could listen to those all day long, I’m sure you have plenty, plenty more, and so I wish we had all day for this and I’m sure our listeners would also be curious. No, but this is great to hear, it’s great to hear how you guys are really on the cutting edge of applying these insights from behavioral science into really doing a lot of good around the world, so I can only applaud that. But I’d like to go back now for a second to your own journey into behavioral science and ask you what were some of the largest challenges you encountered throughout this journey and how did you go about solving those?

Ting: Good question. So I think the biggest challenge I’ve encountered is the human tendency to believe in intuitions rather than evidence, which is related to our own biases of overconfidence and confirmation bias. And I had to deal with this challenge not only when I communicate and work with our partners, but also among our internal team and even myself. Believing in data or evidence rather than intuitions is counter intuitive, by definition, and very difficult to do because our thinking habits oftentimes are very automatic and judging by evidence is not something that we do instinctively and require more deliberative efforts. And so when we are going on our cruising mode of thinking really fast, we tend not to want to believe in the evidence. So having those moments where we pause and say, “What is really the evidence?” And once we have the evidence really digest the evidence and say, “Okay, it’s time that we change our prior.” And not like poking the data until you get something confirming your prior or your intuitions, it’s something that I found most challenging.

Ting: And how did we solve it? For the partnership with Joep Lange Institute we did for a while a quarterly guessing game. So our center is called Advanced Hindsight where we believe that people can explain a lot in hindsight but not in foresight, so people have to … and employees of our partner companies, would have to guess study results before we launched the tests. So we sent a simple Google form and say, “Okay, we have this A, B, and A has his message, B has this message to promote people to save, which one do you think works better?” And then we announce the results after the test is done and we give a prize called the Award of Advanced Foresight. And that worked really well, we gave people maybe a bottle of alcohol or Dan’s Irrational Card Game as a prize, people who won it really was proud of it, even though maybe sometimes they just nominate a more random guess. But the exercise really made our team as well as our partner employees realize how difficult it is to predict actually before the evidence is there, and that our intuitions can really go wrong.

Ting: So if we can truly take the tool of evidence-based approach and experimentation seriously I think there’s so much progress we can make in product design, in programs. But it’s not yet so natural in our system, both in our thinking system and the operational system in companies, so that’s something to be improved on.

Jakob: Interesting, thanks for that. Let me follow up on that point because I’m myself very curious and I’m sure other people out there as well, are there moments in life or situations where you would say that the thinking one, as Dan Kahneman coined it, that automatic thinking, intuitive thinking, is more appropriate and should be followed than the deliberate thinking two system?

Ting: Yeah, that’s a great question. So brushing teeth is appropriate, we just apply system one because we do it every day, we don’t need to think. I’m all about how better to brush our teeth and I do think that there’s a lot of good habits that are in the interest of our health, our happiness, that we haven’t acquired and we haven’t tried, we’re just stuck with those habits since our childhood. And while our context has changed, mobile phones are there, we haven’t actually acquired habits to best cope with these new technologies. And for those I don’t think it makes sense to make a new decision every day, like to brush your teeth or not to brush your teeth, or before bed, to use your phone or not use your phone, I would rather use habit and a rule of thumb and say, “Okay, I’m going to stick to that, it’s better for me not to use my phone one hour before sleep time and I’m going to have a habit of putting our phone in the living room one hour before.”

Jakob: Right. And just because this topic in itself is so interesting, before we move on, what about more difficult life decisions like, I don’t know, picking your right life partner, your right mate, for example? I mean there are people who I think go at it in a very analytical way and look at does this person meet the criteria that one sets for oneself, and then there are these people who kind of, as we say, blindly fall in love, which I understand is more related to that intuitive thinking about somebody. Yet the consequence of that decision can be potentially quite large because ideally you want to find the right partner for a lifetime. So when we move on from habits and still look at more larger life decisions I’m still curious what your research shows, whether in most of these types of decisions it’s better to follow the more reflective, deliberate approach, or are there moments in life where you say that our automatic, intuitive system is still appropriate to be used?

Ting: Yeah. I think in terms of mating or picking your life partners I would say both are needed. We are naturally charmed by people who play good music and who can do sports, well for different people of course there are different tastes in this, but these are things that we’ll any way enjoy for the rest of our lives. It’s not that we made a decision based on how much we enjoy, let’s say, their singing, and then after marriage we simply cannot stand their singing any more, right? So those things are part of the decision based on intuitive thinking and those benefits actually carry on. However, there are aspects where you do want to deliberate over and maybe mating is a more difficult example to think about. Yeah, what aspects do you want to over-deliberate on? But if we think about, say, education choice, what major do you want to study, and again there you do think about what you naturally love and follow your passion but, however, the choice of university and where and for how long and for how much debt, financial loan do you want to take? There are major decisions that you do have to analyze, collect information related to each aspect and analyze systematically.

Ting: And sometimes I do think we have to overcome some intuitive responses intentionally when we know that they are biasing us in a certain way. So if somebody looks really handsome you know that you are naturally inclined to like them, but that doesn’t mean that it would be a good fit for lot of habits, that you’re going to be happy together for spending time together, so you might actually want to discount the look of someone knowing that you have a tendency of over-valuing it.

Jakob: Super interesting, I think that clarifies a lot, thanks, Ting, for that. So let’s shift gears now and I’d like to ask you about the application of behavioral science in projects. So the Center for Advanced Hindsight has a strong reputation because it applies rigorous academic approach to policy projects. This is obviously something that can be very beneficial for organizations that request your services, but it also comes with a lot of challenges. So at times we hear that behavioral science is embraced by project leaders because it provides fresh new and sometimes quicker perspectives than maybe some of the classic economic models have done in the past, but we also hear that units do not have the needed luxury of time and budgets to conduct complex and randomized control trials, yet they still want to apply behavioral science to their projects. So what do you think are the biggest challenges from an organization looking to apply behavioral science in an empirical manner?

Ting: So I think there are two assumptions that you made in your question, so I think one is that experiments are costly in money and efforts, or time. Second, people chose not to apply behavioral science because they cannot afford, say, money or the time needed for RCT. And I actually want to be devil’s advocate here and wonder if they are true. So, one possible explanation of resistance to change, of applying new tools like behavioral science is that people are afraid of being responsible for adopting new ways of working that lead to something worse than if they would have done it with their usual routines, right? So making mistakes by trying something that is not part of their usual routines tend to get blamed from either your boss or other people in your team.

Ting: So this is something I found more challenging than the technicality of RCT, and by the way, a lot of [inaudible 00:27:36] don’t take as much time if we look at the benefit/cost analysis of how much benefits it brought for their project compared to other interventions they would have done that wouldn’t result in as big good changes. So I think a lot is actually the psychological barrier, and how can they be addressed, such barriers? I would say the leadership team of an organization can do a lot about this. So one is to create a culture that embrace risk taking and rewards the process of innovation, and maybe even for those who try new ways or conduct a test but didn’t succeed in finding a good intervention right away, not only they shouldn’t get blamed but they should get comfort to have generated learnings from those failures and try again. So I think that acceptance from leadership level would be crucial for overcoming this challenge.

Ting: And secondly, do start from something small, simple, and costless, because one does need to get familiar with the methodology to invest in something more effortful. So one example is for the very first test that we conducted with the [inaudible 00:29:12] in Kenya, we ran a test comparing two SMS that we sent to users, one says, “Saving as little as 10 shillings to get 100 shillings so that get the bonus of 50 shilling,” and the other we didn’t say save as low as 10, we just say, “Save 100 to get the 50 shilling bonus.” Very simple, and again, we asked people, “Did it make a difference? Which one does better?” And people are either saying it doesn’t make any difference, or they think the effect size is very small, but it turns out that it was huge. It was a really big impact because a lot of people of the low income don’t have more than 20, 30 shillings in their investor and whenever they receive this SMS and look at their balance if it’s very little they feel like they can do it, if it’s save 100, which is a higher anchor, again, it’s a bigger step, more friction and they then think that they will do it later and end up not doing it.

Ting: So getting these sweet rewards from something very simple, very costless, would encourage one to then try more, because early failure can be very deterring psychologically. So that would help. And the last thing is to create a culture in understanding how often, again, our intuitions can go wrong, and really showing that, not just telling them that, “Hey, your intuitions go wrong,” right? So when we mention this game where people and even including the leadership, everybody, kind of joins the game and they all thought that they would have probably made a correct prediction and learned it themselves through this fun way that they could be wrong, and they are confronted with their false intuitions, or they’re proud of themselves when they get it right and aspire to become a behavioral scientist. That’s the moment when the change really starts to take place and not just with a few individuals but it creates a culture of experimentation.

Jakob: Got it. So thank you for that, Ting, that makes a lot of sense, so it goes a bit back to what we just talked about, the intuition versus deliberate, so how the biases can lead us astray sometimes and how it is always worth to question these assumptions by doing some more deliberate data gathering and experimentation, and how often we can then be in a way surprised at whatever our assumptions were actually didn’t out to be reality. And that can have a huge impact in terms of, as you said, cost/benefit, hence it’s worth to take the effort to invest in maybe a bit of a longer process up front, but that can lead to much larger results down the line. So that’s a great takeaway.

Ting, I would like to now go into what I think is a very important topic for the whole application in the field of behavioral science which is ethics. So, as a non profit at the Decision Lab, we are particularly interested in the ethical dimension of nudging, and one compelling argument we’ve heard for why nudging is ethical or can be ethical is that choice architecture happens all the time, whether we think about it or not. Therefore, there’s an ethical imperative to think more deeply and deliberately about how we are doing it. So this is a very interesting view but it brings up further ethical questions, so if nudging gives you a tool to be more deliberate and empirical in the way you affect people’s decisions, how can we make sure that we do this in a way that is as aligned with people’s interests as possible? Is the answer to create this course and let people decide where to be nudged, or should we decide for them based on societal ideals such as being healthy and prepared for retirement?

Ting: Very interesting question, and I actually think your previous question on distinguishing system two versus system one decisions would make sense here. So take brushing teeth again as an example and say, Jakob, you were a very naughty kid when you were small and you really didn’t like brushing teeth so your parents talked to a behavioral scientist and came up a solution, which is they bought different colored toothbrushes and every day they played a game with you on which color did you like to use today. And you ended up brushing teeth happily forever after. Would you actually mind that your parents leveraged you on the psychology of perceived autonomy in nudging you to brush your teeth? Probably not.

Jakob: Probably not, yes.

Ting: Probably not. But if they used those similar tricks to get you to, let’s say, change your choice of major from carpentry to economics and you really didn’t like economics and they nudge you into that, which is a major decision where you could have reflected on it yourself and have your unique preferences, I do think that that’s more problematic. So for daily habits in the interest of health, happiness, let’s say that they tend to be system one, we can use nudge. But for decisions that are related to unique preferences, identity, infrequent and key decisions in one’s life, maybe we still use nudge but the right type of paternalism is not to nudge them not to think about them, or, in the choice architecture, without their own awareness, but actually nudging them to deliberate on them as much and as long as needed. So that we save time from decisions that are more trivial, habitual, where our intentions are aligned with the nudge, but that we don’t do those for very key, infrequent, deliberative decisions.

Ting: And I would even speculate that in 10 years we will all become philosophers, we would finally have time to reflect on the meaning of life because of all the trivial decisions not only tackled more effectively via nudges, but taken out of our choice set to liberate us to think for ourselves in those key decisions. And then we would behave more and more in line with our true identity and unique preferences, if we apply paternalism in the right way. And as you said, it’s key to think about how do we identify decisions where we should nudge and in what way do we nudge, and I find Kahneman’s model of system one and system two actually very helpful in thinking about this question.

Jakob: Makes a lot of sense, thank you, Ting. So, moving on, I’d like to now speak a bit about the whole topic of research in behavioral science with you. So you belong to the group of groundbreaking researchers on the topic of applied behavioral science, can you share with our listeners how you typically choose themes you are interested in researching about, how you link these to behavioral science, and what tools you use for your research? Also, what to you distinguishes good research from bad research in behavioral science? And finally what, I guess, tricks, for lack of a better word, do you use to translate complex academic knowledge to applied work without losing any of its depth and rigor?

Ting: Wow, okay, let me see. So, first question, how did we typically choose themes. Our lab’s number one mission is to make impacts in helping people become healthier, wealthier, and happier, and as Dan puts it we want to reduce human waste in the domain of health, money, time, love, environment. So we pick partners who have overlapping missions with us, and of course it’s fine for us if their goals are also in their business and operational interests, it’s important that we maximize impacts that we can do in these themes, and as long as the themes fit into our missions.

Ting: Your question about how do we link behavioral science and what tools we use for our research; so I would say three things in terms of our processes. One is that we’re collaborative, we collaborate with the practitioners to better identify the problems, the behavioral problems in the work, and this is very important for us and typically we start with the process called behavioral mapping or diagnosis. And the reason why, I think inspired by Einstein’s quote that, “If I would have one hour to solve a problem I would spend 55 minutes trying to figure out what the problem really is and five minutes to come up with a solution.” It’s that oftentimes when we don’t truly understand what is really the barrier and validate it by evidence, we can be intuitively drawn to a solution where we find interesting, instead of really addressing the problem, and looking at things on the surface instead of truly know what’s the problem.

Ting: And figuring that out takes time and often people are very impatient about it, but that’s something that we do differently, that we spend a tremendous amount of time understanding the context, understanding the behavioral problem, understanding whether people don’t do it because they lack the intention to do it, or is it because they have intentional behavioral gap, they forgot to, they lack self control. Or maybe it was not their own lack of intention but that there was lack of supportive social norms, they don’t get respect if they actually do the right behavior.

Ting: So understanding where to intervene on is as important, if not the most important piece. And then we try to pretest and tweak solutions with convenient sample at smaller scale before scaling up, and this is our principle of cost effectiveness. Also because we don’t, again, rely on our own intuitions of the effectiveness of the solutions that we propose, so we only scale up those that we have evidence on its effectiveness. And we are scientific in a way of creating program product solutions, building on also multidisciplinary scientific insights, but also optimizing these solutions via iterative experimentation. So I would say that’s the tools that we use and the processes.

Jakob: Got it, thanks, Ting. And now we are curious to learn a little bit about your viewpoints on behavioral science spreading more and more from what initially what was mainly the public sector to the private sector. So, as many will know, the recent trend of applying not just to improve policies and decision making processes started mainly in the public sector. Your center was-

Ting: Jakob? I’m sorry.

Jakob: Uh huh.

Ting: So sorry, can we … sorry, I do think your question about good research from bad research is helpful, can I just speak one minute on that?

Jakob: Yes, please, go ahead.

Ting: I forgot to answer that question.

Jakob: No problem, go ahead.

Ting: Okay. So then for your question of distinguishing good research from bad research, I would say there is thousands of A/B tests now being run in the name of behavioral science but oftentimes the lesson from some of these tests are not generalizable for a broader different context. And typically because the test fails to reveal the mechanism that drives the effect, so it cannot be abstracted to an insight, it can’t be applied to other contexts. So I would say good research is research that would allow you to understand the mechanism of what drives the effect, so if you know A works better than B you don’t just know it because it works, but also because it’s through addressing, say, self control with reward substitution or increasing attention via highlighting supportive norms. And in those cases you can generalize this to any context that is actually similar to this, knowing better the mechanism. And also the faster the better you can improve, as you will reduce the number of iterations and have clearer directions on what to iterate on.

Jakob: Thank you, thank you for adding that, that makes a lot of sense. So I’d like to go back to my question about now the shift from behavioral science from the public more and more towards the private sector. So your center was actually key in helping the World Bank and other entities to establish their own behavioral science unit, often referred to as nudge units. Today, to a large degree thanks to your efforts, most governments … or also thanks to your efforts, most governments employ as least one or two behavioral scientists. So nudging, or applied behavioral economics, seem to be best suited for effecting public policy, however, after observing the success of nudge units across governments, an increasing number of private sector companies have also followed suit with their own nudge units. So what is your take on the private sector’s increased appetite for applying behavioral science in their businesses, also given the ethical conversation that we had earlier?

Ting: Great question. I think money and profit certainly speaks louder than anything in the private sector; the fact that there is good evidence that applying behavioral science is really effective in improving performance of product design programs is I think what drove the appetite increase. Given the ethical question we had earlier, I do feel sympathetic towards consumers being nudged, sometimes in the wrong way, I think we need to create more awareness of how businesses that are trying to create products in the interests of consumers are the ones that probably in the future will survive the longest because we are having the counter-forces of nudging the consumers to resist temptations from the bad nudges. So it’s not a competition at this point yet, but I think soon enough if we apply in the public policy long enough and substantially enough, we will get to the point that consumers are going to support the businesses with more aligned interests than not.

Ting: So I think for smart businesses who want to succeed in the long run it would be wise to shift gears in profit driven only to also taking into account consumers’ wellbeing, happiness, and health in the calculation.

Jakob: Right and I think you wanted to talk to us a little bit about this new concept of behavioral tech that a lot of people are interested about; are there some thoughts you want to share with us on that topic?

Ting: Oh, yes. So this is something more related to how to create new products, and maybe startup endeavours. So like the concept of fin-tech, which refers to new technologies that seem to improve and automate financial services, behavioral tech, on the other hand, refers to new technologies that improves and automates human participation and behavioral uptake in products, services, and programs such as new tech that would improve behavioral adherence to medications, diet, lifestyle changes and health. And I think systematic application of behavioral tech could be the next breakthrough of innovation, not just in healthcare or public sectors, but also in what kind of products that we would create, invent, for consumers.

Ting: So one example is Shapa, a product created by Dan to help people to lose weight. And there, yes, we have an existing product which is a weighing machine. However, applying insights of behavioral science, Dan went further in tweaking the product so that, one, people don’t get to see how much exactly they weigh, they see color scale instead, and because our human weight actually fluctuates quite a lot during the day and not really linked to the behavior that we have been doing, so it’s oftentimes a bad feedback if we see the weight and we have done, let’s say, good behavior, but then the weight goes up just because we drink a glass of water. So there’s good reason to tweak the product that it would end up helping consumers in stepping on the scale every day and trying to lose weight, adhere to that journey, without … sorry, I think I need to reintroduce Shapa.

Ting: So, okay, let me do it again. An example of this is Shapa, a product created by Dan to help people lose weight. Sorry, got stuck about what would be a good way to introduce Shapa, and we have two minutes left.

Jakob: Yes, and you know what, actually I interviewed Evelyn and she talked a lot about Shapa, so maybe we can skip that and if you want to just keep it a little bit more about the behavioral tech. And I know we have only two minutes so what the other thing is is I can ask you about a career in behavioral science because that’s important to a lot of people, and then maybe we can just go to the ending statement. Is it okay?

Ting: Yeah, when did I say … okay, I said that, yeah, it’s new tech that improves behavioral adherence, blah blah blah, okay. So I can quickly talk about … okay. So where there is people, there is business, and we want to reflect on how the business world can help contribute to human wellbeing by creating products that’s really in the interests of better, healthy behavior and healthy habits. So, as you know, chronic disease are some of the biggest burdens to individuals but also to governmental budgets, and there’s very strong intention of individuals to improve on health. The accumulative cost of chronic disease on middle or low income countries is expected to increase to 11.2 trillion by 2030, so I think we need to empower citizens to take on behavioral change to contribute to welfare, and I dare to say that the country who figured out to push a growth momentum on citizen’s health and wellbeing, not just money or GDP, is going to be the leader of the world of the 21st century, and there’s lots of business opportunities for the private sector in that trend.

Jakob: Got it, thanks so much, Ting, and that’s definitely a topic that we would potentially like to at some point later get back to you because there’s a lot of fascinating stuff happening. So I’d like to shift gears now to our last question which is about how to have a career in behavioral science. So applied behavioral science is becoming an increasingly appealing career choice for many, especially those who want to sit at the intersection between various fields as well as between theory and application. However, for that very reason, it is a tough field to prepare well for, many of our listeners and readers have asked us how they can best prepare for this field. With this in mind, what skills do you think an applied behavioral scientist will most likely need, say in the next five to 10 years, how can they best prepare, and how would you distinguish between a behavioral scientist who wants to be more of a researcher versus someone who wants to do actually applied work?

Ting: Because behavioral science is essentially about understanding human behavior, I think it’s crucial for having good psychological knowledge, and because it’s based on experimentation, evidence based, a good statistical understanding and the skills of doing statistical tests. As for what distinguishes a researcher and an applied researcher, I would say that an applied researcher needs to be more interdisciplinary. So a lot of the interventions that we do are multidisciplinary because of the problems that we tackle and if you are just a researcher I would say probably a bit more focus and lab experiments are oftentimes more clean and the journey is different in terms of how much applied thinking that we can do.

Jakob: As we’re coming towards the end of this chat, we would like to ask what short to long term future you envision for the Center of Advanced Hindsights and what types of project your team is most excited about in the coming years?

Ting: So we are actually very excited about exploring the space of choice architecture, in a literal sense to redesign space at home, at work, in a public space to see how we can embed choice architecture, behavioral science interventions in people’s environment to help them make healthier and happier decisions.

Ting: So not totally that people should be not to exercise more, eat better, but also for social interactions, it tends to be important what are environmental cues are for facilitating meaningful interactions.

Jakob: Fantastic. Thank you. Thank you so much for all your insights today, Ting. We we would like to thank you for your time and wish you and the Center for Advanced Hindsight, all the best for 2019 and beyond.

Ting: Thank you so much.

Jakob: Thanks.

We want to hear from you!If you are enjoying these podcasts, please let us know. Email our editor with your comments, suggestions, recommendations, and thoughts about the discussion.