The Halo Effect in Consumer Perception: Why Small Details Can Make a Big Difference

Many of us have experienced a situation where people discounted something worthwhile that we’ve worked on, simply because one part of it was flawed, even if we didn’t think that that part was particularly important.

For example, imagine the following scenario:

You and your team have been developing a product, and after months of hard work it’s finally ready. Excitedly, you send it out, and then sit back and wait to receive what you’re sure will be glowing user reviews.

But soon the reviews start coming in — and you’re disappointed to see that they’re nothing like what you’d hoped.

“I didn’t like the aesthetic” seems to be the common theme, though it comes in many forms, from the “the design looks bad” to “the color scheme is ugly”.

You understand this to some degree: your focus was on functionality, not looks. Yet, even when users offer feedback on other aspects of the product, it is all much more negative than you expected. It’s as if their entire perception of the product has been influenced by their initial dislike of its appearance.

This scenario can take many similar forms. For example, maybe instead of discovering this issue during testing, you encounter it during the launch of your product. Or maybe instead of a product, it’s a presentation you’re giving to interested buyers. It doesn’t matter much, since regardless of the exact scenario, the problem is the same: a single attribute, such as the aesthetics of something that you’ve created, can substantially affect people’s overall perception of it, even when it comes to other attributes that have nothing to do with it.

The culprit in such situations is a cognitive bias known as the ‘halo effect’, which can cause people’s opinion of something in one domain to influence their opinion of it in other domains [1][2]. A commonly used example of the halo effect is the fact that when we meet other people, we often let one of their traits influence our opinion of their other traits. For example, research shows that physical attractiveness plays a significant role in how people perceive others, even when it comes to judging traits that have nothing to do with looks. This means, for instance, that people rate attractive people as having a better personality and as being more knowledgeable than unattractive people [3][4].

However, as we saw above, the halo effect plays a crucial role not only in how we perceive people, but also in how we perceive other things, such as products. This is important for business and organizations to understand, since it means that consumers’ perception can often be meaningfully affected by the halo effect. This usually occurs at two main levels — the product level and the brand level —and in the sections below we will review examples of both, together with their implications.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

The halo effect at the product level

In this context, the halo effect means any attribute of a product can affect how people perceive its other attributes, as well as how they perceive the product as a whole [5][6]. For example, an unappealing visual design can cause people to perceive the reliability of the product in a negative manner, even if there’s no direct connection between these attributes. Similarly, an appealing visual design can cause people to view a product in a more positive light, even when it comes to attributes that aren’t related to its design.

To illustrate how the halo effect can influence consumer perception at the product level, I worked with the researchers at The Decision Lab to run an experiment on the topic. In this experiment, people were shown one of the two following versions of what they were told is the login page for an app:

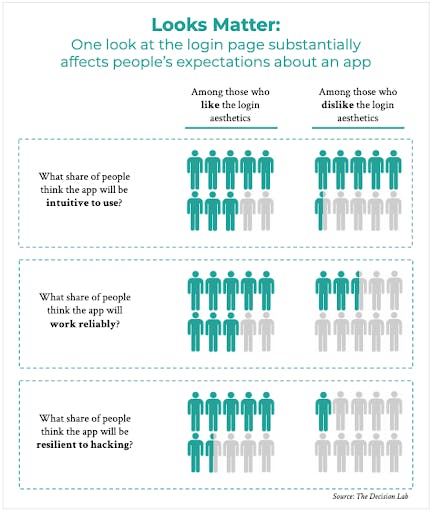

The participants in the experiment were then asked to rate several aspects of the app’s expected attributes, as well as its aesthetics. The main findings of this test are summarized in the following infographic:

For more information about this experiment, both in terms of its results and in terms of methodology, see this complementary case study.

In short, the results of the experiment suggest the halo effect played a noteworthy role in how people rated their expectations of an app after looking at its login page. Specifically, when people liked the aesthetics of the login page, they tended to rate the app as being substantially more likely to be intuitive, reliable, and secure. That is, people extrapolated from the design to form expectations of the product as a whole — despite not having any direct information regarding these attributes, and despite having had no more than a brief look at the login page.

These findings have two important implications: first, that a single attribute of a product, such as its aesthetics, can greatly affect people’s overall perception thereof; second, that people can form impressions based on very little information. In this case, a single look at an image of a login page was enough to substantially influence people’s perception of its aesthetics, and their expectations regarding its other attributes. Of course, as more information about the product becomes available, people’s overall judgments may change — but the importance of first impressions (and salient features) should not be underestimated.

Overall, the key lesson here is that consumers almost never fully disentangle the different attributes of a product from one another — meaning it can be costly to cut corners, even on features seen as unimportant. Moreover, first impressions count, whether it comes to a package for a gadget, a landing page for a website, or anything else associated with your product. Finally, we should note that the same forces at play in our example can equally operate in inverse, meaning the halo effect can positively affect consumers’ perceptions of a product. When developing a product, consider how this knowledge might be leveraged; a simple improvement to the color palette, or the spacing of text, can meaningfully affect how your product is perceived, and in turn your bottom line. Pick the low hanging fruit.

The halo effect at the brand level

It will be no surprise by this point that the halo effect is also present in our perceptions of brands [7][8]. For example, well-executed corporate social responsibility programs have been shown to lend a positive halo effect, which can reduce people’s propensity to take action against a company in light of negative news about it [9]. Furthermore, social responsibility programs in a domain that is visible to consumers, such as recycling, can cause consumers to form a positive perception of other aspects of the company, about which they have little or no direct information, such as its production process [10].

The AI Governance Challenge

Of course, as we saw above, this effect can also be negative. This means, for example, that poor communication with your community or poor customer support can cause consumers to form a negative perception of the reliability of your products, even if the two things aren’t necessarily related to one another, since consumers will not always disentangle their perceptions of your brand. Accordingly, anything from how one of your employees behaves on camera to how your support department deals with a request for a refund may shape, for instance, the perceived functionality of your products. As such, when it comes to ensuring that you have a strong brand, give proper consideration to every aspect of your operations — especially those that you might otherwise neglect.

The halo effect in a broader context

In this article, we focused on how the halo effect plays a role when it comes to products and brands. However, the halo effect can also play a role when it comes to other entities that have to do with consumer perception, such as specific store locations or public figures within organizations.

It’s also important to note that, as with all elements of behavior, there will always be some variability in the manner in and degree to which individuals are affected by the halo effect [11]. For example, research has shown that in some situations, while aesthetics first influence perceived usability, over time this relationship can flip — meaning that usability affects whether people like the aesthetics [12]. As such, while it’s important to account for the halo effect, and remember that it can play a role in any situation where human assessment is involved, it’s also important to remember that our ability to understand and predict its influence is imperfect, and should be treated as such.

Conclusion

Overall, the key points for you to take from this article are the following:

- The halo effect is a cognitive bias that causes people’s opinion of something in one domain to influence their opinion of it in other domains.

- The halo effect can apply when it comes to the perception of both positive and negative factors.

- The halo effect can play an important role at the product level, where a certain attribute of a product, such as its aesthetics, can influence how people perceive its other attributes, such as its reliability — even if those attributes are unrelated.

- Similarly, the halo effect can play an important role at the brand level, where people’s perception of one aspect of an organization, such as its customer service, can influence how people perceive the rest of its operations and the company as a whole.

- There is variability involved in the halo effect, so it may be difficult to predict the exact degree or manner in which it will affect people in any given situation.

Itamar Shatz is a PhD candidate at Cambridge University. He writes about psychology and philosophy that have practical applications at Effectiviology.com

References

[1] The Decision Lab (n.d.). Halo effect. Retrieved August 9, 2019, from https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/halo-effect/

[2] Effectiviology (n.d.). The Halo Effect: Why People Often Judge a Book by Its Cover. Retrieved August 9, 2019, from https://effectiviology.com/halo-effect/

[3] Palmer, C. L., & Peterson, R. D. (2016). Halo effects and the attractiveness premium in perceptions of political expertise. American Politics Research, 44(2), 353-382.

[4] Wade, T. J., & DiMaria, C. (2003). Weight halo effects: Individual differences in perceived life success as a function of women’s race and weight. Sex Roles, 48(9-10), 461-465.

[5] Nielsen J., & Cardello J. (2013). The halo effect. Retrieved August 9, 2019 from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/halo-effect/

[6] Sonderegger, A., & Sauer, J. (2010). The influence of design aesthetics in usability testing: Effects on user performance and perceived usability. Applied Ergonomics, 41(3), 403-410.

[7] Leuthesser, L., Kohli, C. S., & Harich, K. R. (1995). Brand equity: the halo effect measure. European Journal of Marketing, 29(4), 57-66.

[8] Madden, T. J., Roth, M. S., & Dillon, W. R. (2012). Global product quality and corporate social responsibility perceptions: A cross-national study of halo effects. Journal of International Marketing, 20(1), 42-57.

[9] Cho, S., & Kim, Y. C. (2012). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a halo effect in issue management: public response to negative news about pro-social local private companies. Asian Journal of Communication, 22(4), 372-385.

[10] Smith, N. C., Read, D., & Lopez-Rodriguez, S. (2010). Consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility: The CSR halo effect. INSEAD Working Paper.

[11] Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 109.

[12] Minge, M., & Thüring, M. (2018). Hedonic and pragmatic halo effects at early stages of user experience. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 109, 13-25.

About the Author

Itamar Shatz

Itamar Shatz is a PhD candidate at Cambridge University. He writes about psychology and philosophy that have practical applications at Effectiviology.com