Game Theory Can Explain Why You Should Wear A Mask

COVID-19 is no longer a battle against a virus. It is also a battle within society against the uncooperative. Tensions are rising as individuals take polarized stances against safety guidelines. While some are pressing others to socially distance and wear a mask, others are protesting that these are violations of their individual freedoms.

Wearing a mask is one of the recommended methods for preventing the spread of the coronavirus, and there is strong scientific evidence to support this.1 Moreover, in contrast to social distancing and quarantining, wearing a mask is more frequently adopted, easier to follow, and is less restrictive. If more people had decided to always wear a mask, America would have done a far better job controlling the pandemic.

So why are people still electing to not wear masks? In a previous article, I explained the phenomenon of caution fatigue, which describes an individual’s tendency to stop complying with safety guidelines due to depleted motivation and energy.2 This article broke down the behavioral science underlying caution fatigue and provided actionable steps towards mitigating it. These insights can be applied to the decision to wear a mask.

For example, let’s take a look at psychological reactance as a contributor to caution fatigue: After constantly being instructed to wear a mask over time, individuals may purposefully not wear a mask to establish a sense of personal freedom, even if this means dismissing scientific evidence.

Besides caution fatigue and reactance, there are a variety of other reasons for why many consciously elect to not wear a mask. Some complain that they are uncomfortable (difficult to breathe in, hot, sweaty, glasses fog up, etc.). Some have politicized wearing a mask to be a “liberal” action. Others hold incorrect beliefs about the effectiveness of masks.

For example, some believe that masks only protect the mask-wearer, and therefore argue that individuals have the liberty to risk their own safety. Others believe that masks only protect others, and argue that they should not have to experience the discomforts of wearing a mask to protect others’ health. Then, there are some that incorrectly believe that masks are not effective at all.3

In an attempt to convince members of society to wear a mask, many sources utilize science. However, this approach has continued to fail due to the misinformation pandemic, the freedom argument, and a general distrust in authority. Breaking down the decision to wear a mask from a game theory lens provides a rather novel perspective. By modeling assumptions that reflect people’s reasons to not wear a mask, we see that wearing a mask still results in the optimal outcome for society.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

What is the prisoner’s dilemma?

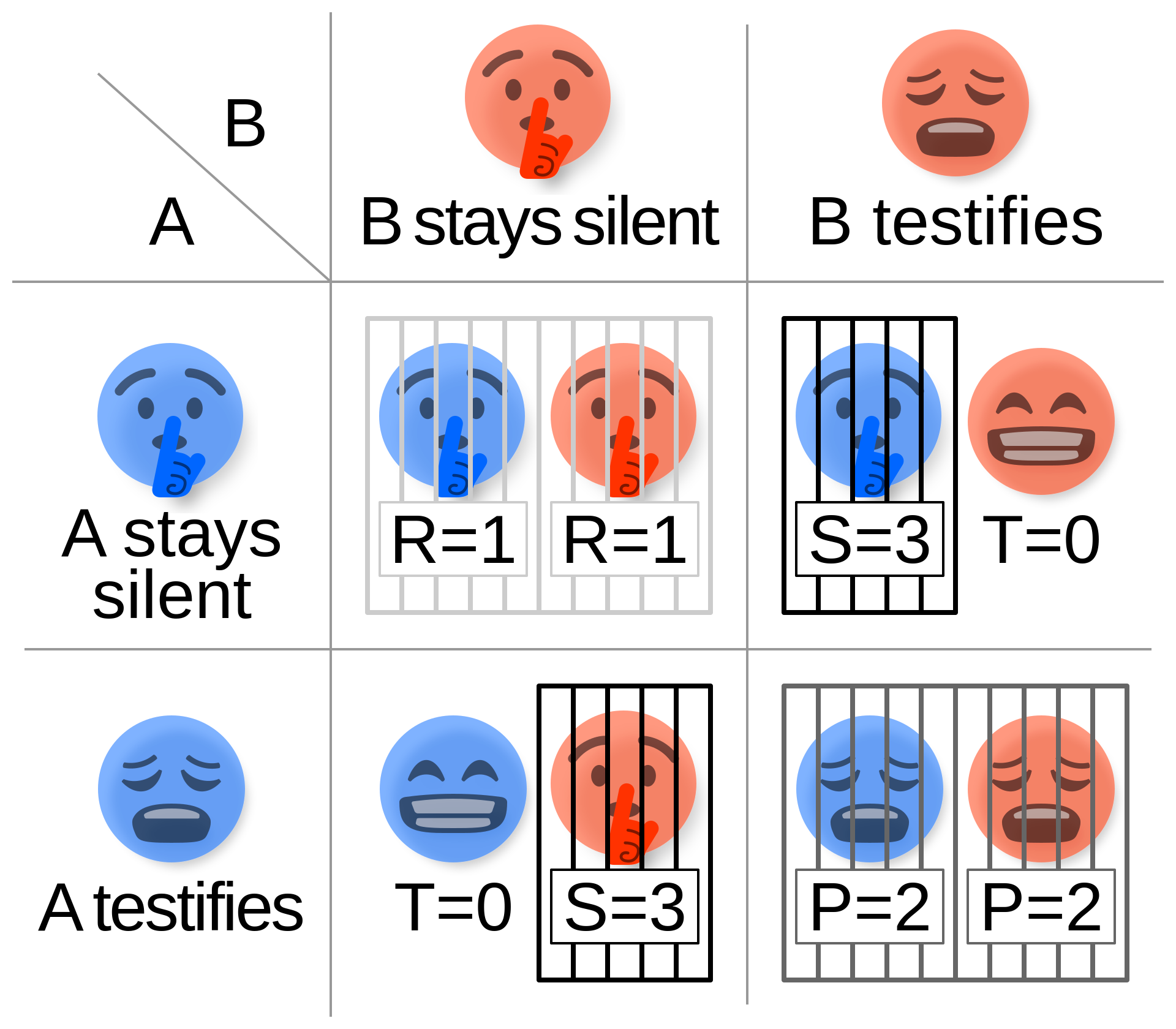

The prisoner’s dilemma is one of the most famous examples of game theory, which is the study of how two parties interact and determine strategies in competitive environments.

In this game, two apprehended bank robbers (Brendan and Jackson) have been placed in separate rooms so that they cannot communicate with each other. Each has two options: to confess or to remain silent. If Brendan and Jackson remain silent, they each get a 2-year sentence. However, if Brendan confesses while Jackson remains silent, then Brendan will only get a 1-year sentence while Jackson receives an 8-year sentence. And vice versa. If both confess, both receive a 5-year sentence. The model below visually represents this game.

Clearly, the optimal outcome is if both prisoners remain silent. However, there’s a paradox, as both Brendan and Jackson are inclined to confess. They may be motivated to receive the 1-year sentence. Or they both fear the result of getting 8 years if their partner confesses. As a result, both confess and receive 5 years — not the optimal outcome.

The prisoner’s dilemma demonstrates how choosing the best outcome for an individual may create a less than optimal outcome overall. And this is often true in the real world, where a lack of cooperation can lead to an inefficient outcome overall.

Wearing a mask and the prisoner’s dilemma

Game theory can help model the decision to wear a mask. Interestingly, we can even model these decisions under different assumptions that reflect the reasons (albeit incorrect) for not wearing a mask.

Let’s define the players of this game as two individuals who have to make the decision of whether they want to wear a mask or not when going out. Like any decision, this decision depends on how the individual evaluates his/her costs (discomfort, ‘loss of freedom’) and benefits (reduced risk of infection, social approval).5

Model 1: The assumption is that masks only protect others around you.

Many believe that masks only protect others and that they offer no self-protection. If this were true, an individual would only receive the health benefits of masks if others around them wore one. This is a common misconception as it is closest to the current scientific understanding of how masks work (to be clear however, science has shown that masks also protect the wearer to a certain extent).

This becomes a paradox that resembles the prisoner’s dilemma. An individual with this belief may act in self-interest and not wear a mask to avoid the discomfort and still receive the health benefits. However, there are likely many others with this belief that may make the same self-interested decision. As a result of this non-cooperation, both players choose to not wear a mask and end up suffering.

The model above visually represents this. The health benefit of the other individual wearing a mask was arbitrarily assigned a value of 10. The cost of wearing the mask was arbitrarily assigned a value of -2. While the most efficient outcome is to have both individuals wear a mask (8,8), the end outcome is actually (0,0).

This model is very similar and equally works to represent the belief set that masks only work when both parties wear one.

Model 2: The assumption is that masks only protect those wearing the mask.

People with this belief set argue that they should have the liberty to risk their own health. For example, I came across one poster held by a protester that read:

“If you’re wearing a mask, why would you care if I’m not? Your mask works, right?”

Of course, this is not how the virus works — by electing to not wear a mask, you are also risking others’ lives. Nevertheless, let’s structure our model around this belief set to see if cooperation results in the most efficient outcome, regardless of this belief’s accuracy.

In the above model, individuals who don’t want to wear masks clearly believe that the benefits of not wearing a mask (avoiding the discomfort and feeling ‘free’) outweigh the potential health consequences. Therefore, we need to readjust the values we assign. We can do this by negating the values so that the cost is greater than the benefit. For example, the benefit of wearing a mask can equal 2 and the cost of wearing a mask can equal -10.

Based on this, the optimal outcome for both individuals would be to not wear a mask. This is the outcome that provides the highest utility to both individuals separately and as a group.

The AI Governance Challenge

However, translating this to the real world shows that this might not necessarily be the case.

While the immediate cost of not wearing a mask may be a negative impact on your health, the pandemic continues to surge when a large number of people choose this route. As a result, your favorite restaurant may remain take-out only. You’ll continually abide by the mandatory mask restrictions at stores and buildings. NFL football remains closed. Paradoxical, isn’t it?

It is important to recognize that there are other players besides just individuals such as public/private entities who make decisions based on the statistics of the pandemic. As a result, our costs and benefits are not limited to the short term, and we may be blindsided by present bias. This makes a strong case for why cooperating and wearing a mask might, in fact, be the highest utility outcome.

Model 3: The assumption is that masks offer no protection, or that the virus is a fabricated hoax

Yes, some people still don’t believe that the coronavirus really exists, or that it is not dangerous. This results in the decision to not wear a mask. Similarly, those that believe that masks offer no protection whatsoever will also decide to not wear a mask. In such cases, the perceived benefit (mask’s effectiveness) of wearing a mask is 0, and the cost (discomfort) of wearing the mask is still -2.

If these incorrect beliefs happened to be true, then the optimal outcome for society would be to not wear a mask, right? Well, it’s not that simple. Masks are more than just protective gear — they are a signal of cooperation and responsibility. While some individuals may believe that masks are not protective, others still do. In fact, most Americans do believe that the pandemic is dangerous, regardless of whether it actually is or isn’t. So how does this affect society?

Let’s consider the economy. During the initial shutdowns, US consumer spending significantly decreased. After re-opening the economy, spending increased again, but not quite to its original levels. Even a 10% decrease from the baseline spending levels can spell out an economic catastrophe characterized by high unemployment and recession.

One contributing factor to why spending hasn’t returned back to normal is because many people are still concerned about the dangers of the virus. This may be due to the fact that people still see many others deciding not to wear a mask.

And thus, cooperation again results in an optimal outcome for society, even when we disregard any of the ‘controversial’ beliefs around the health dangers of the virus or the effectiveness of wearing a mask. Reopening the economy only works if everyone is convinced that it really is safe to go outside. By not wearing a mask, you send the opposite signal, thereby depressing the economy by persuading others to stay inside.

Final Takeaways

Game theory shows us that, regardless of what an individual believes, it is in their own self-interest to wear a mask.

While the conflict surrounding wearing masks will persist, these insights shed light on a new perspective on the benefits of wearing masks during this time, even outside the realm of public health and science. Next time you encounter a family member, friend, co-worker, or even a stranger who is against wearing masks, consider explaining that their decision, although self-interested in the short-run, only hurts them in the long run.

Just like in the prisoner’s dilemma, cooperation results in the most efficient outcome. If we cooperate and wear masks, the pandemic will be better mitigated and we may finally find true freedom again.

References

1. CDC. Considerations for Wearing Masks. 7 Aug 2020 [cited 13 Aug 2020]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

2. Andhavarapu S. How To Remain Vigilant In The Era Of COVID-19 Information Overload – The Decision Lab. 13 Jul 2020 [cited 12 Aug 2020]. Available: https://thedecisionlab.com/insights/health/how-to-remain-vigilant-in-the-era-of-covid-19-information-overload/

3. Wang J, Pan L, Tang S, Ji JS, Shi X. Mask use during COVID-19: A risk adjusted strategy. Environ Pollut. 2020;266: 115099.

4. Lumen Learning. Prisoner’s Dilemma. [cited 13 Aug 2020]. Available: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-microeconomics/chapter/prisoners-dilemma/

5. Li W, Zhou J, Lu J-A. The effect of behavior of wearing masks on epidemic dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. : 1.

About the Author

Sanketh Andhavarapu

Sanketh is an undergraduate student at the University of Maryland: College Park studying Health Decision Sciences (individual studies degree) and Biology. He is the co-Founder and co-CEO of Vitalize, a digital wellness platform for healthcare workers, and has published research on topics related to clinical decision-making, neurology, and emergency medicine and critical care. He is also currently leading business development for a new AI innovation at PediaMetrix, a pediatric health startup, and previously founded STEPS, an education nonprofit. Sanketh is interested in the applications of behavioral and decision sciences to improve medical decision-making, and how digital health and health policy serve as a scalable channel to do so.