Why do we underestimate the influence of the situation on people’s behavior?

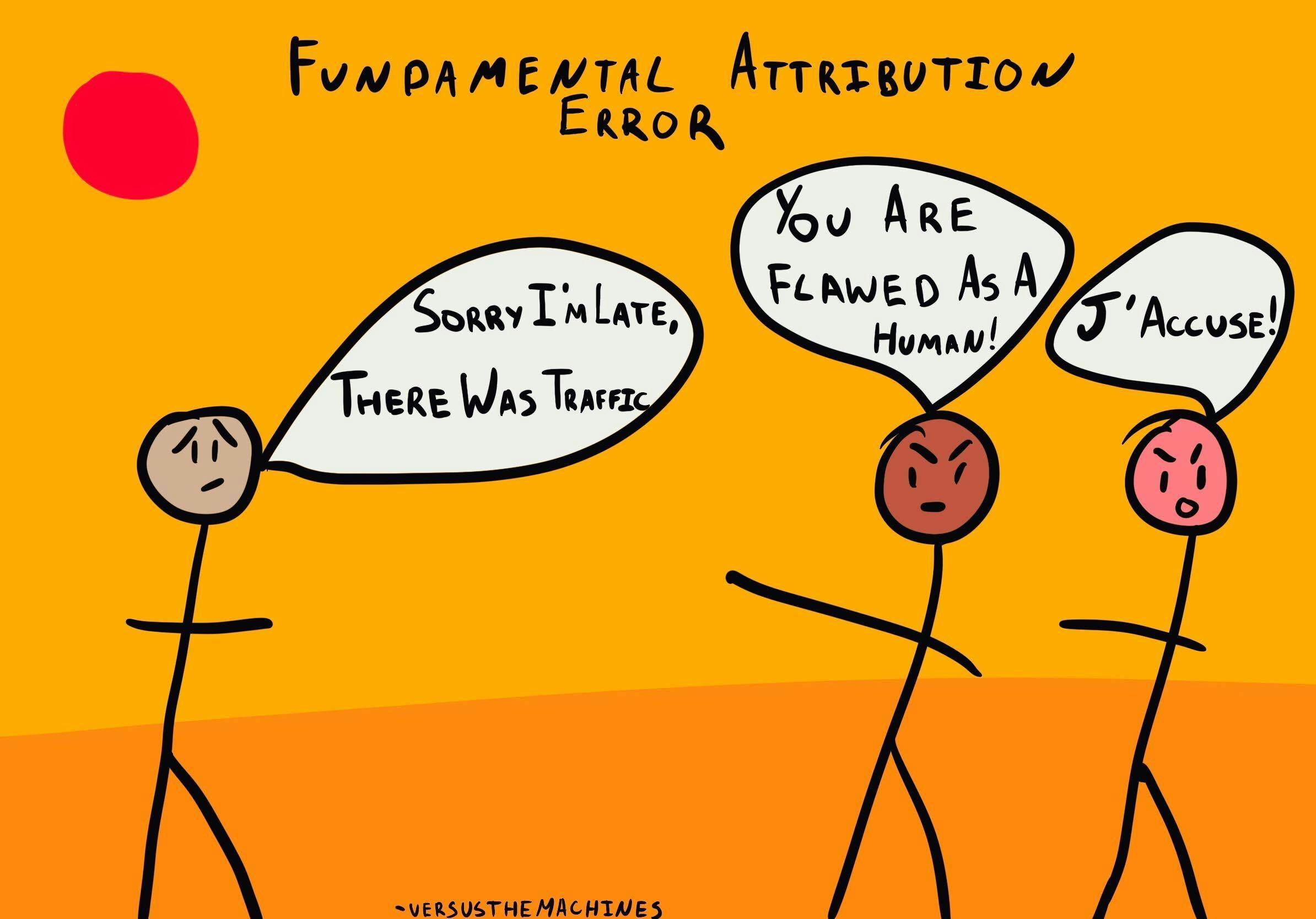

Fundamental Attribution Error

, explained.What is the fundamental attribution error?

The fundamental attribution error (FAE) describes how, when making judgments about people’s behavior, we often overemphasize dispositional factors and downplay situational ones.5 In other words, we believe that people’s personality traits have more influence on their actions, compared to the other factors outside of their control.

Where this bias occurs

Let’s say you’re driving to work one day, and somebody cuts you off. Furious, you decide that the other driver is a selfish person, who doesn’t care about other people’s safety. Unbeknownst to you, the other driver rarely cuts people off, and normally they are very careful about safety—but right now, they’re on the way to a hospital for a family emergency, so they’re acting differently than they usually would.

The fundamental attribution error causes us to make fast, and often incorrect, assumptions about others without taking into account that there may be another reason for the observed behavior. It often occurs in situations where we know little information as we attribute people’s behavior to situational or dispositional factors.

Individual effects

Because of the fundamental attribution error, most of us walk around believing that dispositional factors (that is, people’s personality traits) are more powerful than situational ones. In other words, we assume that no matter what the circumstances, an individual’s actions will still generally reflect what they are like as a person. This can cause us to make unfair and incorrect judgments about people, discounting possible reasons that might have contributed to their behavior.

This means that the fundamental attribution error also causes us to make inaccurate judgments about others. This can lead to a deficit in our interpersonal relationships as we do not afford others the benefit of the doubt when their actions are guided by situational factors. Further, this can lead us to perpetuate biases and stereotypes which are harmful not only on an individual level but a systemic level.

Systemic effects

We are particularly likely to fall victim to the fundamental attribution error when considering negative behavior, including what we consider to be immoral. This can become a barrier to addressing systemic issues in our society as we are quick to negate the situational factors that play into someone’s behavior or observable actions.

The FAE vs. the actor-observer bias

The fundamental attribution error is often associated with another, similar phenomenon, the actor-observer bias (also known as actor-observer asymmetry). According to this cognitive bias, people have a tendency to make dispositional attributions for other people’s behavior, and situational attributions for their own. In other words, while we like to explain our own actions in terms of the various external factors when it comes to other people, we are quick to say that they act the way they do because that’s just the “way they are.”1

For example, if you do really poorly on an exam, you may be inclined to blame external factors in order to rationalize the result. You may cite that your teacher did not properly relay the material and concepts or that your exam was much harder than that of your peers. You negate the factors that implicate your own shortcomings, like the fact that you only studied the night before or that you missed your teachers' tutorials.

The FAE vs. the correspondence bias

Similar to the fundamental attribution error is the correspondence bias. For a long time, the two terms were used interchangeably, before a number of researchers started to argue that they were distinct.5

While they describe the same phenomenon, the correspondence bias focuses on our tendecy to infer larger, and more unchanging, aspects about peoples’ personalities based on their behavior. 4,5 Put another way, we assume that people’s actions correspond to their core internal attitudes. Meanwhile, the fundamental attribution error focuses on how underestimating the impact of situational factors lead to these incorrect assumptions.

While these biases are now considered separate, the fundamental attribution error can contribute to the correspondence bias. For example, let’s say you are watching a classmate give a presentation. They seem nervous: they’re sweating, fidgeting, and stuttering. The fundamental attribution error might cause you to downplay the fact that the situation (giving a class presentation) is stressful for most people. In turn, the correspondence bias could lead you to infer from your classmate’s behavior that they must be an anxious person in general.

How it affects product

The fundamental attribution error can play a large role in brand reputation. When a product fails to meet consumers' expectations, they are likely to attribute its performance to poor design and quality testing. Seldom do we consider legitimate manufacturing defects or user errors. A prime example would be a software bug on a new online video game. Rather than considering the error to be a fixable mistake, some may be inclined to believe that the game company produces below-par products. Frustrated with the outcome, one doesn't consider that perhaps the servers were overloaded by the influx of new players, causing the platform to crash.

On the other hand, when purchasing a winter jacket, the tag will typically indicate the temperature it can withstand. Wearing that jacket in temperatures exceeding what was shown on the tag may lead to feeling cold. That doesn't necessarily mean that the product is terrible and that the company produces low-quality garments; it is the situation in which you put the jacket that leads to its poor performance. Before judging a product or a company, it is essential to consider the situational factors that occur during use that cause the product not to work as advertised.

The FAE and AI

When working with artificial intelligence, the prompt that we give the system makes all the difference in the response that we receive. In order to get high-quality output, certain conditions need to be met in the phrasing of the question.

Novice AI users may not be privy to the nuances of AI prompting. This could lead to inaccurate or low-quality responses from the software. In turn, users will infer that artificial intelligence is not helpful or valuable, when in reality, it can be a useful tool to enhance big-picture and everyday tasks alike. This is an example of the fundamental attribution error at work: we negate the “situation” that the software is in when we incorrectly prompt it and attribute the poor responses to the platform itself. Being too vague in our question formulation will lead to vague responses that don’t quite hit the mark of what we are looking for. This can discourage us from turning to AI software for future endeavors which can put us at a disadvantage.

Across the web there are various resources that can be consulted in order to perfect prompt engineering. Most will stress the importance of being detailed and specific, as well as providing clear context to the problem you wish to solve or data you wish to collect.14

Why it happens

Although we all understand that people’s behavior is shaped by the situations they find themselves in. Very few people would try to argue that everybody behaves in exactly the same way, regardless of the circumstances. The problem is not that we lack situational theory (i.e. awareness of the power of the situation). Rather, the fundamental attribution error comes up when we fail to apply this understanding properly.3

Sometimes, we don’t account for the situations simply because we lack awareness.6 Without all of the relevant information, we can’t make a reasonable judgment about someone’s behavior. However, as research has shown, people often commit the fundamental attribution error even when they’re fully aware of what’s going on.

In a classic study piloted by Edward Jones and Victor Harris, university students read essays that either defended or criticized Fidel Castro, the leader of the Communist Party of Cuba. Some participants were told the writer had chosen whether to write for or against Castro, while others were told the writer was assigned a position. The researchers were surprised to find that, even when participants were told the writer hadn’t chosen which side they would be on, they still believed that the author’s opinions about Castro were consistent with the argument they made in the essay.7 Further research has confirmed that this effect is observed independent of participants’ own opinions. It also shows up when they have been given extra information about the writer, and even when warned to avoid bias.3

So, why do people commit the fundamental attribution error even when they should know situational factors might be at play? There are a few different reasons this might happen.

Accounting for the situation takes up mental resources

In some cases, the fundamental attribution error seems to happen because it takes effort to adjust our perception of somebody’s behavior to be more in line with the situation they’re in. We have limited cognitive resources, and generally speaking, our brains like to take the route that expends as little energy as possible. This leads us to take cognitive shortcuts (known as heuristics), which also makes us vulnerable to a whole raft of cognitive biases.

When we are mentally processing somebody else’s actions, there are three steps we need to go through. First, we categorize the behavior (i.e. what is this person doing?). Second, we make a dispositional characterization (i.e. what does this behavior imply about this person’s personality?). Finally, we apply a situational correction (i.e. what aspects of the situation might have contributed to this behavior?).3

While the first two steps seem to happen pretty much automatically, the third step requires more of a deliberate effort on our part—meaning it often gets skipped over, especially in situations where we don’t have the cognitive resources to go through it. For example, this could happen if we’re distracted by something else, or if we don’t have time for it.

Empirical evidence confirms this explanation. In one study by Gilbert and colleagues), participants watched a silent video of a woman who was behaving anxiously. For some participants, subtitles in the video indicated that the woman was being interviewed about topics that would make most people uncomfortable, like sexual fantasies. For others, the subtitles showed an interview about relatively boring topics, such as ideal vacations. On top of this, the researchers also manipulated the participants’ cognitive capacity, by telling some of them that they would have to take a memory test about the interview topics afterward. Participants who were told about the additional quiz were partially distracted while they watched the video, as they tried to commit the topics to memory.

The results of this experiment showed that, when participants were distracted, they were more likely to make dispositional attributions for the woman’s anxiety. In other words, their explanations for her anxious behavior related to stable qualities of her personality: they said she was an anxious person in general. Meanwhile, participants who didn’t have to worry about a test only made dispositional attributions if they had seen the boring version of the interview because those who had seen the anxiety-provoking version understood and evaluated that she was made uncomfortable by the questions.8

The FAE is affected by our mood

Other research has shown that we are more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error when we’re in a good mood, compared to when we’re in a bad mood. In one study, based on Jones & Harris’ Castro experiment, participants read essays that were for or against nuclear testing and then made judgments about the writer’s opinions on the subject. However, this study had an added twist. Before reading the essays, the participants completed a verbal abilities test, where they had to complete sentences such as “a car is to the road as the train is to…” The questions ranged from easy to hard, including several that didn’t actually have any one “correct” answer (such as “Bread is to butter as the river is to…”).

To manipulate participants’ moods, once they finished the test, an experimenter told them that they’d performed either above or below average. After this was done, they went on to read the essays, with some being told that the writer had picked their argument and others told that they had been forced to argue a specific side. The results of this study showed that happy participants were more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error, but only when the writer had been assigned an opinion and argued for an unpopular stance.9

Why would this happen? Overall, it seems like being in a bad mood can make us more vigilant and systematic in our processing, which helps us to pay closer attention and retain more information. In fact, compared to participants who were put in a bad mood, happy participants were able to recall fewer details about the essay they had just read, suggesting that good moods can actually impair memory.

The fact that participants were more prone to the fundamental attribution error only when they had read an essay with an unpopular opinion might also indicate that they were relying on heuristics, or stereotypes, about people who hold that opinion, and that their happy mood made them less likely to question their reliance on those stereotypes.

To sum up, being in a good mood might make us process our environment in a more careless way, making us more susceptible to taking shortcuts—and less likely to make it through that final phase of situational correction.

Sometimes we ignore the situation on purpose

As we have seen, if we’re low on cognitive resources or something else is clouding our processing, we might skip the situational correction phase and end up committing the fundamental attribution error. But other times, even when we have the cognitive capacity to think things through, we might choose to neglect the situation anyway. This happens when we believe that a behavior is highly diagnostic (i.e. indicative) of a specific personality trait.

To explain this, let’s look at immoral behaviors, such as stealing or doing harm to another person. Studies have shown that people tend to think of immoral behavior as highly diagnostic of immoral personalities. In other words, people think that somebody must be an immoral person in order for them to do something immoral. By contrast, they don’t generally apply the same logic to moral behaviors—so, somebody who steals an old lady’s purse is assumed to be an evil person, but somebody who helps an old lady across the street isn’t necessarily a saint.4

When we’re considering behaviors that we see as highly diagnostic, we believe that they are necessary and sufficient for us to make judgments about the person doing them. This leads us to fall victim to the fundamental attribution error.

Why it is important

From time to time we all play the role of the psychologist in our day-to-day lives. We are constantly trying to figure out why other people act the way they do and make decisions about others based on their behavior. When the fundamental attribution error leads us to make incorrect judgments about other people and their actions, this can harm our relationships with others and negatively affect how we interact with them in the future.

The fundamental attribution error also has broader societal consequences. As discussed above, we are especially likely to fall victim to this error when it comes to perceived immoral behavior, which often lines up with the kinds of things that are criminalized in our society—for example, theft or drug use. This means we are biased to ignore situational factors that might have led somebody to behave a certain way. In turn, this can lead us to ignore systemic factors, such as discrimination, that contribute to criminal behavior and other negative outcomes, and fixate solely on individuals. Overcoming the fundamental attribution error will likely be an important step toward fixing these broken systems.

How to avoid it

As we have seen from the experiments above, the fundamental attribution error is a tricky bias to overcome: it defies what we know about a situation and the world, and pushes us to draw irrational conclusions. However, even though it’s not possible to completely avoid this bias, there are steps you can take to correct your quick judgments.

Put yourself in the other person’s shoes

One of the best antidotes to the fundamental attribution error is empathy.10 It’s easy to blame other people’s conduct on some permanent fixture of their personality, especially when we view that behavior negatively—but it’s hard to keep feeling that way once you imagine how you’d feel in their position. If the roles were reversed, you would probably want other people to give you the benefit of the doubt, and understand that your mistakes aren’t necessarily reflective of who you are as a person.

To counter the fundamental attribution error and improve relationships more broadly, one helpful goal is to build emotional intelligence (EI). EI includes empathy, as well as self-awareness, self-regulation, along with other traits. Building emotional intelligence is a longer-term project and something that individuals must be constantly working towards. It can involve exercises such as regular journaling, or even taking a course with a professional.11,12

Focus on the positive

As people, we are all multifaceted; we have our good traits, and we have our bad ones. If you find yourself feeling resentful towards somebody for something they did, try to remind yourself of their better qualities, and that this one action probably doesn’t represent them fully.11

How it all started

The question of how we understand other people is fundamental (pun intended) to social psychology, and many thinkers have addressed it in different ways over the years. In the 1930s, Kurt Lewin, one of the pioneers of modern social psychology, wrote about the importance of situations in determining people’s behavior, an idea that became central in his work and in the field more generally. The power of situational factors became even more important after World War II, when social psychology made it its mission to understand how it was that human beings could perpetrate the horrors of the Holocaust.

Decades before Jones and Harris conducted their Castro study, and before Lee Ross coined the term “fundamental attribution error,” the psychoanalyst Gustav Ichheiser wrote that a “social blindness” often led people to ascribe others' actions to their personality traits: “Many things which happened between the two world wars would not have happened if social blindness had not prevented the privileged from understanding the predicament of those who were living in an invisible jail.”6 Despite this, the fundamental attribution error (and the related correspondence bias) weren’t formally studied until the 1970s.

Example 1 – Social Scientists

Apart from its effects on everyday life, the fundamental attribution error is important to keep in mind in the context of social science research and how we interpret it. In his 1977 article on the fundamental attribution error, Lee Ross discussed its relevance to social psychology in particular.2

If you’ve ever taken a psychology class, you’ve probably read about classic social psychology experiments such as the Milgram study (which tested how far people’s obedience of authority could be pushed) and the Asch studies (which were about conformity). According to Ross, the reason that many of these experiments have become so famous and influential is because of the fundamental attribution error. Their results, which demonstrated the power of the situation, were memorable only because people—including the social psychologists conducting and reading about these studies—are susceptible to believing that the internal factors of the participants are stronger than external ones in the experimental conditions. In other words, their impact depended on the fundamental attribution error.

Example 2 – Racial Bias

Perhaps unsurprisingly, research has found that people who are generally less prone to the fundamental attribution error are also less likely to endorse racist beliefs. People seem to vary in their “attributional complexity,” a trait that describes how people generally explain the behaviors of others. Attributionally complex people are more motivated to explain human behavior, have a preference for complex rather than simple answers, and have a stronger awareness of the power of social situations on human behavior.

Naturally, these traits make people less likely to fall for the fundamental attribution error, and they also tend to have fewer racist beliefs. In one study, researchers measured participants’ racism by having them rate their agreement with various statements (e.g. “Differences between ethnic groups are innate”). They also measured attributional complexity, using statements like “I don’t usually bother to analyze and explain people’s behavior.” The results showed that attributional complexity was statistically associated with racism.13

Summary

What it is

The fundamental attribution error describes how we overemphasize a person’s internal traits when trying to explain their behavior and underemphasize situational factors.

Why it happens

Generally speaking, the fundamental attribution error happens because adjusting our perception to account for the situation takes effort, and we might not always have the time or cognitive resources to do so. Other times, we ignore the situation because we believe that it’s not relevant, instead seeing behavior as diagnostic of certain personality traits.

Example 1 - Social science and the FAE

As Lee Ross wrote when he coined this bias, the impact of many classic social psychology studies depends on the pervasiveness of the fundamental attribution error. The only reason that studies such as the Milgram experiment are so surprising is because people, even psychologists, are susceptible to the belief that a person’s disposition is more powerful than the situation.

Example 2 - The FAE and racial bias

Research has shown that attributional complexity, which makes people less likely to commit the fundamental attribution error, is inversely correlated with racial bias. In other words, the more attributional complexity, the less racism.

How to avoid it

In a nutshell, avoiding the fundamental attribution error requires empathy, and a deliberate effort to achieve a more balanced view of a person and their circumstances. Building emotional intelligence and gratitude for a person’s good qualities is helpful.

Related TDL articles

Why We Sometimes Favor Aggressive Political Leadership

The effects of the FAE can be seen in the political sphere, especially in recent years, as more aggressive approaches to governance are gaining traction all over the world. Why do people respond more positively to so-called “hawkish” leaders? This article discusses how the FAE skews our perception of politicians who ordinarily take a hardline stance, especially when it comes to diplomacy and negotiations.

10 Decision-Making Errors that Hold Us Back at Work

In this article, Dr. Melina Moleskis examines the common decision-making errors that occur in the workplace. Everything from taking in feedback provided by customers to cracking the problems of on-the-fly decision-making, Dr. Moleskis delivers workable solutions that anyone can implement.