In the very first class of my Masters in Behavioral Science, our professor wrote in capital letters on the whiteboard: “CONTEXT MATTERS.” I still have my notes from the class where I doodled around these two words, not really understanding their gravity or the reasoning behind why this was being emphasized.

Cut to now. A few weeks ago, the entire world of behavioral science was shaken when a blog made startling revelations about the validity of some high-profile research in behavioral science.1 But that’s not even the first time the field has been called out. The replication crisis has bogged us down for years.2 Yet, somehow, when I read these articles, my main response is not alarm, but rather the conviction that my doodle drawing of “Context Matters” from so many years ago really was correct.

The reason I say that is because being an applied behavioral scientist basically means all the research we do starts from scratch, irrespective of replicability or conclusive laboratory results. Each analysis is in a completely new context, and possibly with a completely different audience.

How then do we make use of all this academic literature? What’s the point of academic literature if it fails in a different context? How do we make sense of what works and what doesn’t?

Les sciences du comportement, démocratisées

Nous prenons 35 000 décisions par jour, souvent dans des environnements qui ne sont pas propices à des choix judicieux.

Chez TDL, nous travaillons avec des organisations des secteurs public et privé, qu'il s'agisse de nouvelles start-ups, de gouvernements ou d'acteurs établis comme la Fondation Gates, pour débrider la prise de décision et créer de meilleurs résultats pour tout le monde.

Frameworks to the rescue

After a few years of asking myself these questions, I have come to the conclusion that consultants and MBAs were not completely off the mark with their dependence on frameworks. A framework distills the research on a given topic into its core insights and helps connect various components in a meaningful way, to help people understand how complex behavioral mechanisms work in practice. Some prominent frameworks include the MINDSPACE framework and the COM-B model.

But how do we go about creating such a framework? Let’s take an example of a framework and try to understand how we go about creating it.

Last year, I wrote a piece for The Decision Lab on why we cannot say no to promotional offers. It was a basic framework synthesizing various theories for how promotions or discounts are perceived by consumers.

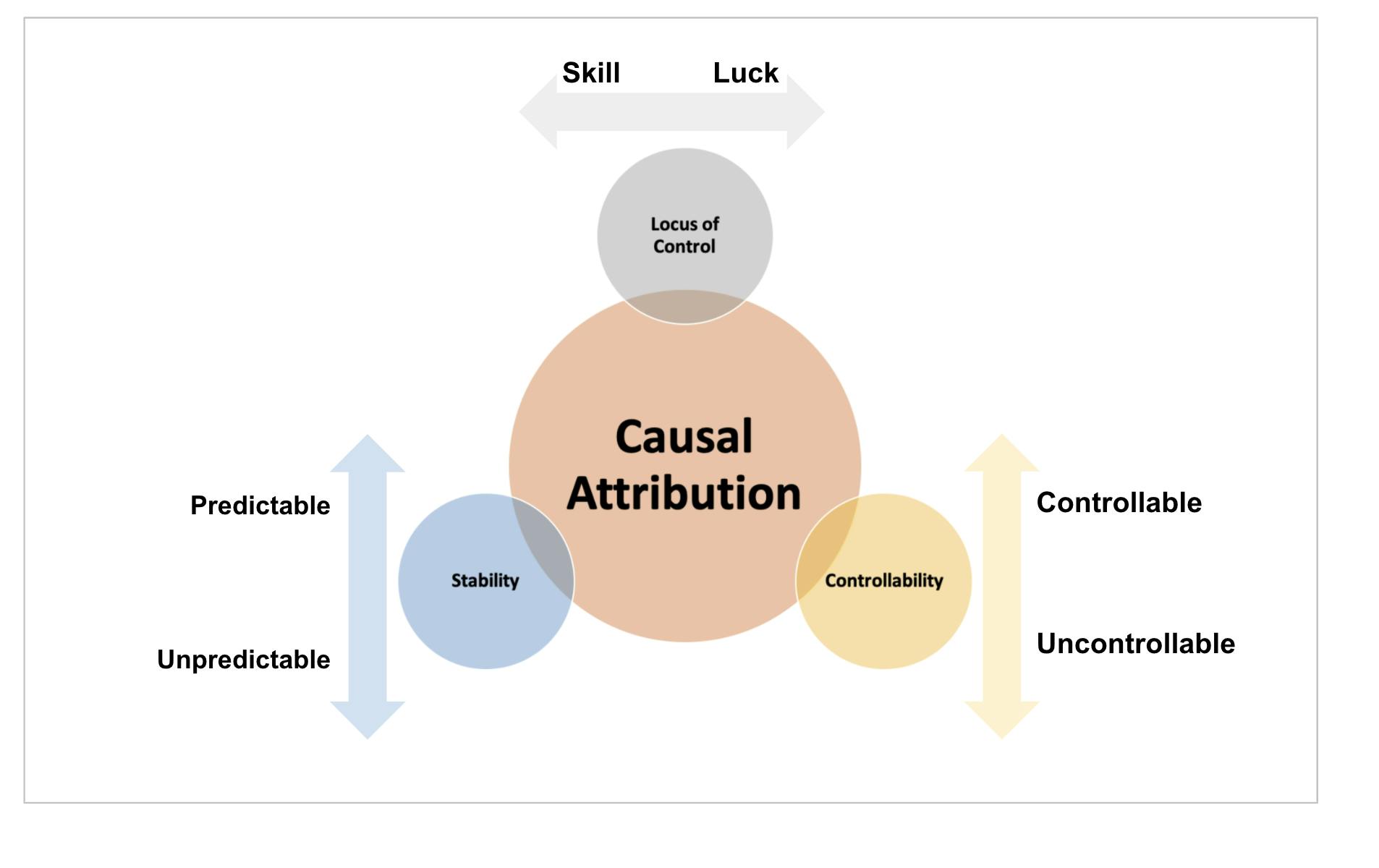

In this area, there are two dominant hypotheses: the Lucky Shopper hypothesis and the Smart Shopper hypothesis. According to the former, consumers enjoy discounts the most when they come about as a result of external factors; by contrast, the latter states that consumers appreciate discounts more when they deliberately found them under their own power. It’s a question of luck versus skill.

Now, if you look into the literature, you’ll find papers that state that the Lucky Shopper hypothesis cannot be proven; you’ll also find others that say it is the most valid explanation for why people love discounts. The same is true for the Smart Shopper hypothesis. But when you dig deeper into these papers, you’ll also realize that none of these are conclusive in either direction, because they worked with small sample sizes, were run as surveys instead of randomized controlled trials, and basically cannot be taken at face value.

That said, that doesn’t mean all this research is useless. These papers still tell us that in certain circumstances, certain factors impact decisions in a certain way. That is still important information—it just needs to be contextualized within the wider body of research. That’s where frameworks come in.

In short, my framework looked like this:

This framework doesn’t center either hypothesis, but instead creates a model for weighing various factors to predict how people might perceive discounts in certain situations.

Why make frameworks?

- They provide an exhaustive list of influences. What happens if we don’t go through this process? Let’s take something as simple as loss aversion. Loss aversion is a disputed topic. Are people averse to loss? Maybe they are. Maybe they are not. But, if we go by whichever paper we’ve most recently read and categorically ignore the potential influence of loss aversion on a decision, we risk missing a valuable part of the picture.

Maybe in our context, because of how our brand is seen by customers (premium brand) or because of the category we operate in (for example, insurance or financial services), people are really averse to loss. A framework that incorporates any and all biases that may or may not come into play, and then allows practitioners to determine to what degree it is relevant, will ensure that we don’t fail to detect an important influence on people’s behavior. - They provide a more fundamental understanding. As an applied behavioral scientist, your solution cannot be a single, one-line statement telling the team what nudge to apply. It has to be a nuanced understanding of human behavior that helps all stakeholders comprehend the behavior at a fundamental level. A framework helps you do that. It just helps everyone understand all factors that can influence a behavior.

- They help us solve a variety of problems. When you create a framework, you help open up the problem space. If anything can influence behavior, you should be solving for as many things as possible. A framework approach helps the entire team think through problems keeping in mind these multiple influences and thinking of ways of overcoming them.

So, how does one create a solid framework?

- Assemble an exhaustive list of inputs. This is where the massive academic literature comes in handy. Comb through literature and find all possible publications on the subject. Some may not be proving anything conclusively. Some may support the exact opposite conclusion of what you intend. The only thing that matters is, you collect as much information as possible on everything that impacts the behavior you are trying to study.

For instance, in order to create this framework on discounts, search for all possible research around promotions, offers, transactional utility, and so on. Sometimes, even adjacent literature, like literature on casinos, might give you clues. Make a note of all things that impact the behavior. Conclusive, inconclusive, positive, negative, does not matter. - Connect the dots in logical order. Armed with the list of inputs, think of logical ways in which you can connect them. Some will merge together, some will stay separate entities. Skill and luck are opposite ends of the locus of control, so they come together. A few factors come together and become “controllability.” And so on.

- Now run the framework in different contexts. Knowing that we created this framework as an exhaustive list, it is important to run the framework in different contexts and come up with case studies on when a factor works and when it doesn’t.

For instance, based on your research, you can now you can say that the Smart Shopper hypothesis seems to be relevant when purchasing products like electronics, because consumers put in the research before deciding what exactly to buy. When they find themselves a discount through extensive research, they feel better about themselves. However, for the same people, the Lucky Shopper hypothesis might still apply in some cases, like when given a scratch card to get a week’s worth of groceries for free. These shoppers may find themselves overjoyed, because they got “lucky.”

The important thing is—there are no limits. Everything can be applied to everyone, theoretically. But, how can that be feasible? - That’s why you experiment! Now you know all factors that can impact how people feel about discounts. But how do you know exactly which of these is at work in your particular context? You experiment. The framework merely laid down the guiding principles to help you come up with all possible experiment ideas. Create an exhaustive list of influences, design experiments around them, weed out ideas that seem unreasonable or intuitively wrong, and finally, decide what to experiment on. Only at the end of the experiment, you conclusively know what is working in your context.

Why now?

In the recent debates about the validity of behavioral science research, several troublesome factors have come up. Are these studies valid outside university labs? Are these studies valid for audiences outside of the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) world? Are these studies valid under all contexts? Are these studies going to be true a few years from now? Are these studies replicable?

In the midst of all this intense debate, there are two learnings for all behavioral science practitioners:

- Overreliance on one study to prove all these above factors is misguided. No study is able to conclusively prove everything.

- Focusing on proving the existence of one effect on one small audience may or may not result in research that stands the test of time.

Instead, the whole mental model around understanding human behavior is gradually shifting from focusing on one influence to a more nuanced understanding. Frameworks reflect this changing paradigm, transforming behavioral research from a black-and-white understanding of human behavior to a more holistic model. As an applied behavioral scientist, I have been witness to this transformation and can vouch for the increased practicality of behavioral science thanks to this shift towards frameworks.

Concluding remarks

Do frameworks always work? Maybe not. But, given what we know about our subject, we also know that drawing conclusions based on academic research alone is also not reliable.

Like my first day in behavioral science taught me, context matters. Frameworks help test academic research in different contexts more rigorously. They give us a means of respecting academic literature and at the same time, adapting it for practical use. If none of the factors in your framework end up working for you, you know there’s a gap in the literature. But if even one factor works, you know the framework helped you rule out so much more. Just for that, it’s worth the effort.

References

- Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L., & Simmons, J. (2021, August 25). [98] Evidence of fraud in an influential Field experiment about dishonesty. Data Colada. https://datacolada.org/98

- Yong, E. (2018, December 7). Psychology’s replication crisis is running out of excuses. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/11/psychologys-replication-crisis-real/576223/