If you’ve ever taken an Econ 101 class, you’re familiar with the concept of opportunity cost. It’s the idea that, when making decisions, you should always consider what else you could be doing. Essentially, opportunity cost is about the value of time, captured by the phrase time is money.

Of course—as it originates in the world of economics—opportunity cost doesn’t touch on concepts like memory or perception. But what if our goal was to maximize the length of our psychological lives rather than the size of our bank account? In that case, when choosing between experiences, we would have to consider the memories that each experience would beget. A slogan for this kind of experiential opportunity cost could be time is memory.

In a previous article, I discussed some of the psychological quirks that warp our perception of time. One of the takeaways was that novel experiences expand our perception of time, whereas routine ones contract it. We can choose to break out of our routine every now and again, and take that vacation to Venice. By doing so, we accrue new memories, and our psychological history lengthens. From this perspective, a life spent in the doldrums of routine seems downright wasteful. Still, since most of us value routines, habits, rituals, and skill-building, something seems to be missing from this picture. We can’t shake off the niggling suspicion that psychological time maximization—in the form of memory-collecting—shouldn’t be our single, overarching goal.

Les sciences du comportement, démocratisées

Nous prenons 35 000 décisions par jour, souvent dans des environnements qui ne sont pas propices à des choix judicieux.

Chez TDL, nous travaillons avec des organisations des secteurs public et privé, qu'il s'agisse de nouvelles start-ups, de gouvernements ou d'acteurs établis comme la Fondation Gates, pour débrider la prise de décision et créer de meilleurs résultats pour tout le monde.

Memories at the cost of experiences

One way to assess the value of memory-collecting is to test its impact on our two selves: the experiencing-self (which evaluates our moment-to-moment experiences) and the remembering-self (which evaluates our memories of those experiences).1 At first glance, novel experiences seem to perform pretty well—a moonlit stroll through Venice’s cobbled alleys is pleasurable in the moment as well as in retrospect. A closer examination, however, reveals that our novel experiences often favor the remembering-self at the cost of the experiencing-self.

Daniel Kahneman’s famous thought experiment cleverly illustrates this trade-off.2 Imagine you are planning a week-long vacation and have to pick between two options: either you sacrifice rest and comfort and go backpacking across Europe, or you catch up on sleep and sanity with a relaxing week of margaritas by Venice Beach. Here is the catch: afterwards you will take a pill that will wipe every second of the vacation from your memory. No mental or physical photographs would remain, only the experiences themselves at the time you experienced them. So, which vacation would you take?

While your answers may vary, the amnesia pill almost certainly plays a pivotal role in your decision process. This is because the vacation that offers the most robust and durable memories is not the same vacation that provides the most relaxing and rejuvenating experiences. In other words, the satisfaction of one self is purchased with the dissatisfaction of the other. And when it comes to vacation-planning in particular and decision-making in general, we usually err on the side of pleasing the remembering-self. We don’t put much weight on the sleep deprivation, achy feet, or travel anxiety the experiencing-self will endure. Rather, we imagine our future cosmopolitan selves, who will forever bask in the afterglow of our globetrotting escapades.

This built-in trade-off, between pleasing ourselves in the moment and satisfying ourselves upon recollection, forces us to pick between three options.

Option 1: We can claim that one of the selves is the “real” self, and only that self should matter. Kahneman initially theorized that the experiencing-self was our true self, and chalked up people’s emphasis on the remembering-self to good old human error. Of course, one could just as easily make the case for the supremacy of the remembering-self, in which case memory-collecting would be a valid goal, regardless of the initial experience.

Option 2: We can accept the futility of this line of analysis and abandon the project altogether. This is the option that Kahneman ultimately settled on, after he concluded that people’s incorrigible fascination with the remembering-self rendered option one untenable.

Option 3: We can attempt to balance the satisfaction of the selves, in which case the objective of memory-collecting must be tempered with other competing, and sometimes incompatible, objectives. As you may have guessed, I’m a fan of this last option. Unfortunately, this bring us back to square one, because routine—the ultimate psychological time-shrinker—is chief among these competing objectives.

Why practice if experience doesn’t change?

So how can it be worthwhile to spend large chunks of our lives in the grip of unmemorable routines? Neither the remembering-self nor the experiencing-self seems to be all that fond of dull repetition. In fact, one of the conditions of deliberate practice—the kind of practice needed to achieve expertise—is that it is uncomfortable.3 To top it off, it isn’t clear that the improvement that comes with routine practice even has a positive impact on our experience. Consider the following scenario:

Quarantine is in full steam and you can feel yourself morphing into a couch potato. Finally, you put your foot down. Enough is enough. You resolve to begin a follow-along yoga routine at home. But soon you discover that your motivation to stick to your self-imposed workout schedule pales in comparison with your desire to break the world record for consecutive hours binging Netflix.

A friend floats a great idea—why don’t you play a sport? Tennis was your go-to sport as a kid, so you decide to give it a try. Luckily your friend lives nearby, your work schedules are similar, and the weather is at its best. At first, the tennis is a blast. Admittedly, neither of you is remotely consistent or in the vicinity of graceful, but it feels great to get outdoors, soak in the sun, and hang out. Plus, the challenge of simply getting the ball over the net is so demanding that you are both fully locked into your rallies. Exercise has never been so fun and easy.

As time goes on, you and your friend begin to take private lessons. Eventually your high pops and accidental slices evolve into topspin lobs and perfectly placed drop shots. Your matches with your friend are just as competitive as before, but the joint quality of your tennis has improved drastically. Still, after one of your tightest matches—one in which you double faulted match point in a third-set tiebreak—you can’t help but be seized by a bout of frustration. All of that practice and for what!

Later that night an odd realization hits you—even though your tennis game has evolved and your matches have acquired a new intensity, the enjoyment you feel while playing has remained relatively stagnant. If anything, it may have taken a nosedive. After all, the same accidental slices that you used to laugh off now set off a stream of four-letter words.

Going with the flow

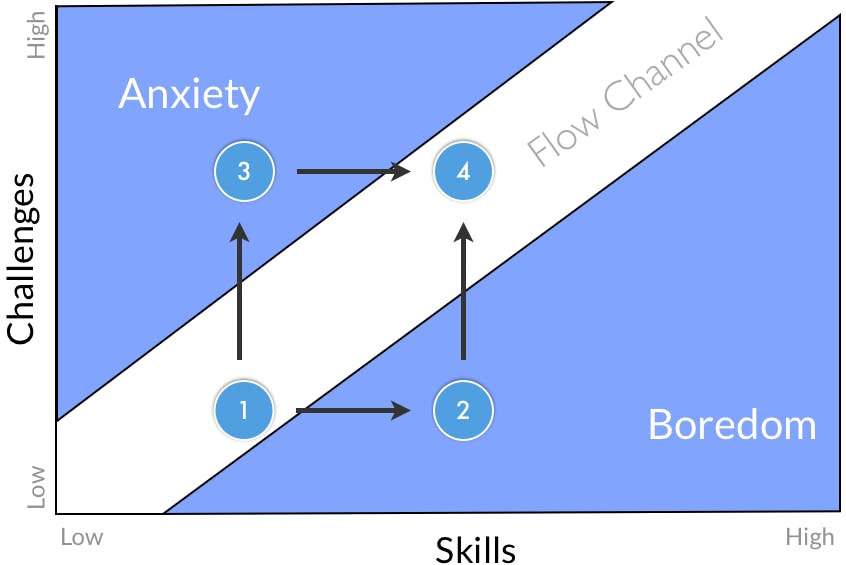

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi charts this phenomenon in one of the most useful graphs I have ever encountered (see below).4 If you take a look at the graph, you’ll see that the y-axis represents the challenge of an activity and the x-axis represents the skill level of the performer. The flow channel is the sweet spot where the skill level just meets the challenge level. As Csikszentmihalyi puts it: “enjoyment appears at the boundary between boredom and anxiety, when the challenges are just balanced with the person’s capacity to act.”

Source: Bailey, C. (2013, September 12). How to ‘Flow’: Here’s the most magical chart you’ll come across today. A Life of Productivity. https://alifeofproductivity.com/how-to-experience-flow-magical-chart/

When you and your friend were tennis novices, you were in position 1, parked comfortably at the foot of the flow channel. The two of you were at similar skill levels, so the challenge was always just enough for you to handle, keeping you fully engaged. Because the two of you trained in tandem, you skirted the banks of anxiety and boredom and sailed straight up the flow channel together, making it to position 4 in just a few months. The counterintuitive insight here is that, even though your respective skills have drastically improved, position 4 delivers similar levels of enjoyment to position 1. This begs the question: why practice at all? Why seek out position 4 when you are just as happy as you were at position 1?

While there are many possible answers to this question, the most glaring one shouldn’t be overlooked: we really like being good at stuff. As Harry Harlow showed with rhesus macaques and Edward Deci with graduate students, we enjoy tasks and activities that offer no external reward, because the intrinsic rewards of improvement and achievement are plenty in and of themselves.5,6 Humans crave competence, especially when it comes to the tasks and activities that their identities and self-narratives are built around.7 Often, we aren’t satisfied with just hitting the ball around; we want to be excellent tennis players. And the only way to become excellent at anything is to build up to it incrementally. As the adage goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day. We must grit our teeth and endure hours and hours of frequently unmemorable and frustrating, yet ultimately rewarding practice. Real mastery is the progeny of routine.

The silver lining of a pandemic

While quarantine puts a damper on most potential activities, routines get away largely unscathed. In the previous article, I emphasized the importance of novel experiences and changes of scenery to counteract the warping of time that goes hand-in-hand with quarantine. I stand by this sagely advice.

But there is still the question of what to do with your remaining downtime, all that time that used to be spent hanging out with friends, but is currently being squandered on Friends reruns. The truth is that there has never been a better time to practice those scales, start that workout, or perfect that swing. And although the day-to-day details of your routines may not last in your memories, they will change the character of your future experiences, and will therefore endure in the memories of those experiences. In the long run, you’ll remember those heated matches with your friend fondly. When your kids get their first rackets, you’ll be able to teach them how to hit with topspin yourself. Wimbledon matches will become thrilling to watch, as you finally appreciate the beauty of Federer’s stroke. You’ll be in considerably better shape without having suffered through a minute of an interminable workout. And for all these benefits, you’ll have routine to thank.

References

[1] Kahneman, D., & Riis, J. (2005). Living, and thinking about it : two perspectives on life. Thinking, 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2006.02.047

[2] Kahneman, Daniel. “Transcript of ‘The Riddle of Experience vs. Memory.’” TED, www.ted.com/talks/daniel_kahneman_the_riddle_of_experience_vs_memory/transcript?language=en.

[3] Ericsson, K. A., & Ward, P. (2007). Capturing the naturally occurring superior performance of experts in the laboratory: Toward a science of expert and exceptional performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6)

[4] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Row.

[5] Harlow, H. F., Harlow, M. K., & Meyer, D. R. (1950). Learning motivated by a manipulation drive. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 40(2), 228–234.

[6] Deci, E. L. (1972). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22(1), 113–120.

[7] Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being, 55(1), 68–78