Do High-Potential Employee Programs Work?

Despite its massive impact on a global scale, Twitter is a relatively small company. With five thousand employees, Twitter has to find the right potential leaders in their organization to invest in and promote. If Twitter chooses 5% of its workers to label as “high-potential”, they can spend millions of dollars on this set of 250 future leaders. Let’s take a look at what might happen inside a company like Twitter when putting its high potential program into place:

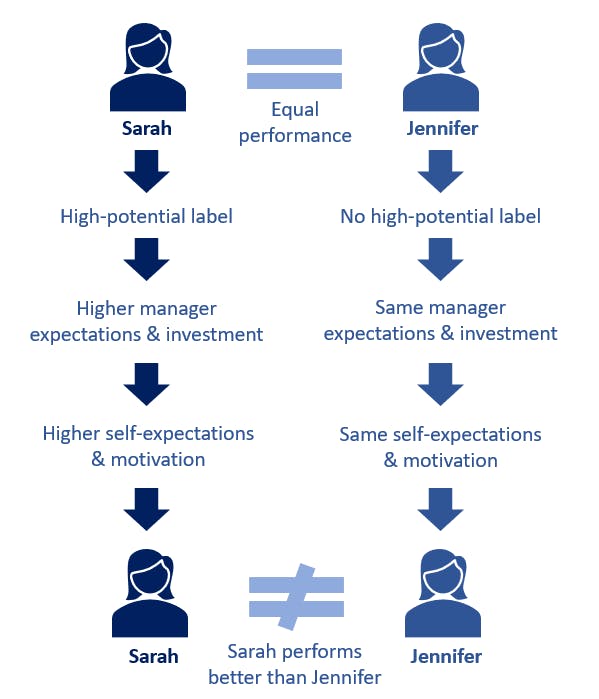

Sarah and Jennifer are two equally good employees managed by the same boss, Alex. One morning in June, after their performance reviews, Alex finds out Twitter labeled Sarah as a high-potential employee. Months later, the two women learn how their performance changed since their June review. Sarah’s performance skyrocketed, while Jennifer is doing just as well as before. Nothing changed around them except their boss knew about the high-potential label.

What happened?

High-potential programs in companies are built with good intentions. Firms wish to find talented people to invest in so they can put these employees on a fast track to leadership roles. These programs have a lot of power. What if they are simply creating self-fulfilling prophecies?

The Pygmalion effect

The Pygmalion effect describes a type of self-fulfilling prophecy that happens when other people’s expectations of us lead us to perform better. This self-fulfilling prophecy happens frequently in the workplace, but it was discovered first in elementary schools.1 In 1968, researchers told primary school teachers that some kids were “late bloomers” and others were not. Even though kids in both groups started at the same IQ level, the late bloomers blossomed.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

The AI Governance Challenge

Here’s the catch: The researchers picked the late bloomers at random — they had no special qualities or high potential compared to the rest of the students. But the teachers’ belief in the late bloomer group improved their intelligence. By the sheer force of high expectations, a randomly-selected group made the researchers’ prophecy come true.

Simply naming someone as “high potential” changes their performance, by changing others’ expectations of them

Soon enough, studies showed the same Pygmalion effect with therapists, nurses, and managers.2 Clients in treatment for alcohol abuse were more likely to succeed if they were labeled “motivated” compared to others who were “unmotivated” — even if the label wasn’t true.3 Nurses and aides treated nursing home residents differently if experts said they would progress faster in their rehab compared to those labeled as “slower progressors”.4 These fast-healing residents had fewer hospital admissions and had fewer depressive symptoms, despite the labels meaning nothing at the start.

How does this work? For the most part, it occurs under our conscious awareness. Teachers, nurses, therapists, and managers don’t even remember treating one group differently than the other. Despite this, professionals of all kinds act differently towards people who have higher potential. Teachers give high-potential students more challenging work, more constructive feedback, and act friendlier to them.5 Leaders act differently toward high-potential teams by showing them more enthusiasm, encouragement, coaching, and confidence.6

Our expectations of others are below our conscious awareness, but they change how people perform.

Leaders influence their employees’ actions directly with differential treatment. They also create a self-fulfilling prophecy by changing workers’ expectations about themselves. When researchers take employees’ self-expectations into account, the Pygmalion effect goes from explaining 32% of the improved performance to only 6%.6 This means high-potential labels can raise leaders’ expectations, which in turn raise workers’ expectations, which improves their performance. Sometimes this process is even shorter: When companies tell employees they are on a high potential track, this works to increase the employees’ own expectations. This means the high-potential label is enough to improve any randomly selected employee’s performance. Below is a visual explanation of Sarah and Jennifer from our story above.

Telling employees or their managers about their high-potential status raises employees’ self-expectations

Now that we know high-potential programs can create a self-fulfilling prophecy through the Pygmalion effect, what can we do about this? Companies can take three big steps to strengthen their high-potential system:

1. Identify the right people by making better decisions about who should be labeled as high-potential

Any program in your organization is only as good as the data you put into it. If your methods for choosing talented workers is flawed, then your program will be flawed in the same ways. This means you need more accurate, relevant data on the skills and success of applicants during your hiring process and from your performance management system. For example, performance reviews are influenced by how confident and busy an employee seems. These aren’t good measures of potential or performance. Instead, measure performance through team members’ evaluations and objective progress towards employees’ goals.

If you choose to create (or improve) your high-potential process, focus on the quality of your decisions. After all, people who look like leaders are still seen as having more leadership potential than others who don’t fit the stereotype.7

2. Question your assumptions about what it means to be talented.

Is talent something that only some people have? Is talent innate or can it be developed? Your company’s views on these two questions shape the way they might approach high-potential programs, as their goal is to find and invest in talented employees. Below are the four ways companies think about talent and their implications for development programs.8

This talent matrix shows the underlying assumptions that come from believing talent is exclusive vs inclusive and static vs dynamic.8If your company follows the static and exclusive approach, you can design a limited high-potential program that focuses on keeping these employees happy but doesn’t try to change their performance. Instead, a company following the dynamic and inclusive approach would invest in all its employees with customized programs that match their interests and career path. When developing a talent program, companies should choose whether they will train everyone, a few select people, or none at all.

3. Consider who needs to know about the high-potential label

So far, we can see how high expectations help employees by increasing their motivation and performance. Yet high expectations can backfire or have other unintended consequences. That’s why you should match your talent development approach in section number 2 with the transparency level that works for your company’s culture. If your company has a competitive, cut-throat culture, sharing employees’ high-potential status with each other could backfire. As well, if you have an exclusive approach to talent, transparency might hurt your overlooked employees even more.

High-potential programs can shape companies’ and employees’ futures. They are risky because the large investment in workers can become a self-fulfilling prophecy if programs are not designed well. This raises questions about how useful these expensive programs are. Why are employees spending so much time in leadership training academies, if telling their boss about their high-potential label works just as well, and for free? If anyone can rise to our expectations, it’s time to question our beliefs about who has talent and who doesn’t.

References

1. Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. The Urban Review, 3(1), 16-20.

2. Kierein, N. M., & Gold, M. A. (2000). Pygmalion in work organizations: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(8), 913-928.

3. Jenner, H. (1990). The Pygmalion effect: The importance of expectancies. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 7(2), 127-133.

4. Learman, L. A., Avorn, J., Everitt, D. E., & Rosenthal, R. (1990). Pygmalion in the nursing home: The effects of caregiver expectations on patient outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 38(7), 797-803.

5. Rosenthal, R. (1994). Interpersonal expectancy effects: A 30-year perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3(6), 176-179. & Harris, M. J., & Rosenthal, R. (2005). No more teachers’ dirty looks: Effects of teacher nonverbal behavior. Applications of Nonverbal Communication, 157-192.

6. Eden, D. (1990). Pygmalion without interpersonal contrast effects: Whole groups gain from raising manager expectations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(4), 394-398.

7. Biermeier-Hanson, B. (2012). Looking like a leader: an investigation into racial biases in leader prototypes. (Accession no. 1505574). [Doctoral dissertation, Wayne State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

8. Meyers, M. C., & Van Woerkom, M. (2014). The influence of underlying philosophies on talent management: Theory, implications for practice, and research agenda. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 192-203.

About the Authors

Zad El-Makkaoui

Zad El-Makkaoui is an Organizational Psychologist, consultant, and people strategist. She is an associate at an organizational development consulting firm called gothamCulture. Her research interests include organizational change and the Future of Work. Zad has a MA in Social-Organizational Psychology from Columbia University and a BA in Psychology from the American University of Beirut. She is a certified Team Diagnostic Survey Advanced Practitioner and is a CIPD-certified L&D Associate.

Natasha Ouslis

Natasha is a behavior change consultant, writer, and researcher. She started her own workplace behavioral science consulting firm after working as a consultant at fast-growing behavioral economics companies including BEworks. Natasha is also finishing her PhD in organizational psychology at Western University, specializing in team conflict and collaboration, where she completed her Master of Science in the same field. She has a monthly column on workplace behavioral design in the Habit Weekly newsletter and is a Director and science translator at the nonprofit ScienceForWork.