Brave New World: How the Metaverse May Shape Our Psychology

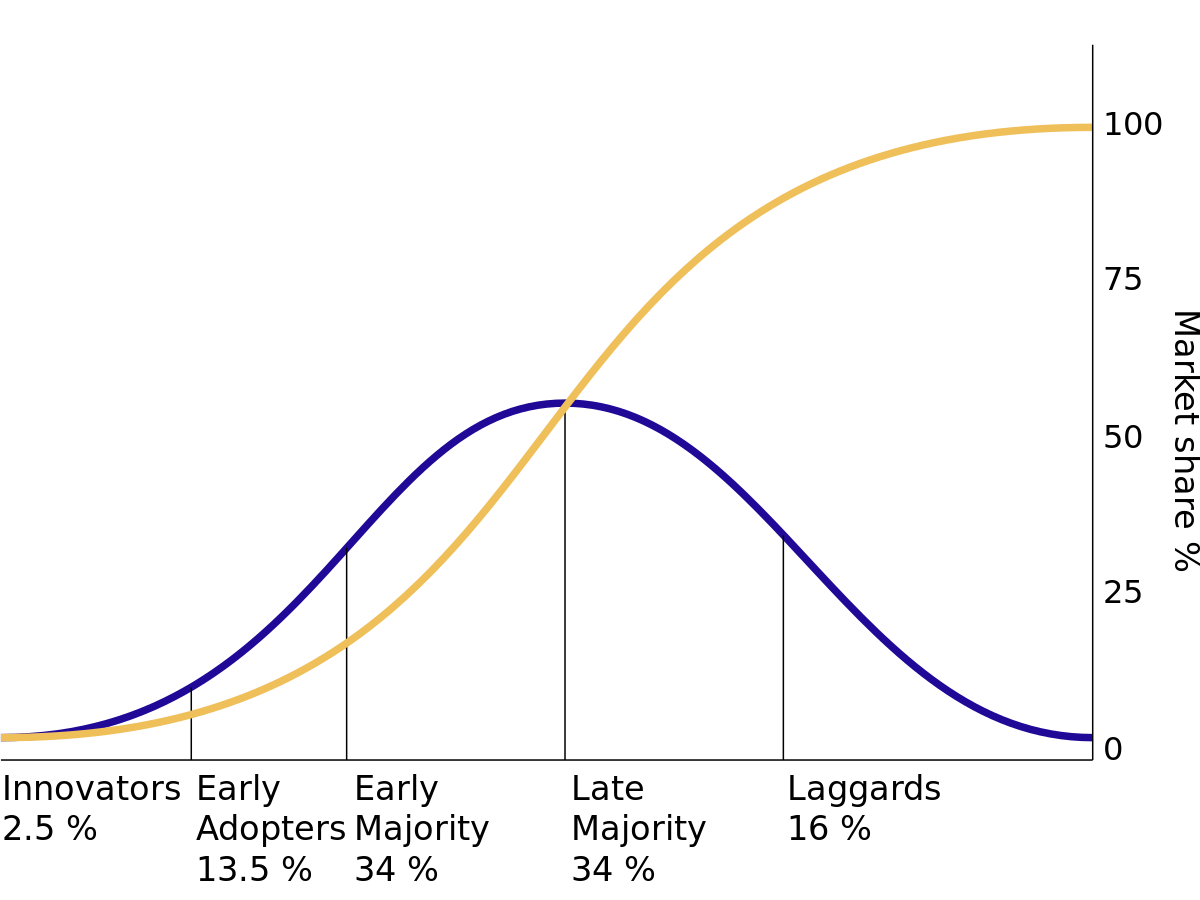

In a book published in 1962 called Diffusion of Innovations, communications theorist Everett Rogers presented a most convincing theory of how innovation spreads and comes to be accepted by users over a period of time. He posited that any new product is initially used only by a small number of innovators, followed by a slightly larger group of early adopters and then the majority.

But what happens when the negative side effects of a product don’t emerge until after some time has passed? A certain level of adoption will already have been secured before people realize any harmful effects exist. And even if the unforeseen harms of a product become clear after some time, the product is already diffused throughout a large chunk of the population. The negative effects may not be enough to stop the momentum that is causing the harmful product to spread fast.

At a certain point, you can’t put the toothpaste back into the tube.

This is exactly what happened with social media. I still remember when it was actually cool to post a status or a check-in. We didn’t think about how the red dot notification was actually kind of ruining our lives. We didn’t think about data privacy. We didn’t imagine how polarizing this seemingly harmless product could be. We just enjoyed using it to stay connected with friends and family.

At some point, we realized that there was a lot was wrong with social media. But we still didn’t abandon it completely — I wouldn’t be surprised if you came across this article while browsing on a social feed. We even complain about social media on our social media.

The irony is, as all-consuming as social media may be, it’s really just the beginning. From social media, a whole new world of new immersive experiences is emerging, with the hope of more engagement and more connections. I am referring, of course, to the world of the Metaverse.

The question, then, is this: does knowing the negative effects of the product put us in a position of being able to do something about them in the future?

The AI Governance Challenge

The Metaverse: Social media, supersized

I would assume, unless you have actively resolved to stay off the grid, you would have heard of the Metaverse. It is the next big thing in the tech community. To catch you up, Facebook is now called Meta,2 and they have explicitly shifted their focus to bringing social experiences into the Metaverse. Microsoft made a similar strategic move and invested in a gaming company called Activision, with the aim of leveraging video games as a portal to the Metaverse.3 Banks are buying “land” in the virtual world of Metaverse, to get a leg up on real estate in a world that does not physically exist.4

Just in case all of this sounds too dystopian, let’s take a step back. How did we get here?

When COVID-19 hit us, and we were all thrown into a world where our devices were our only connection to the outside world, a silent revolution was brewing in the world of gaming. Through the universes of games like Animal Crossing and Fortnite, people discovered (or perhaps just doubled down on) an escape route.

Gaming was a way to forget the outside world and immerse themselves in a virtual one, where they could take on any form, wear whatever they wanted, be whoever they liked — a new environment where they controlled everything. And they liked what they saw. Companies quickly realized that the future was here and started jumping on the bandwagon, announcing plans for a virtual world.

It wasn’t completely new, though. The origins of the Metaverse go back to 1992, when science-fiction author Neal Stephenson first coined the term in his book Snow Crash. In the universe of the novel, the “Metaverse” is an urban environment that users can access by donning virtual reality goggles.5 Stephenson probably never guessed his imagination was going to become the thing that moved the stock market 30 years later.6

So what really is the Metaverse? Matthew Ball has the most comprehensive definition I have seen so far:

“The Metaverse is a massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds which can be experienced synchronously and persistently by an effectively unlimited number of users with an individual sense of presence, and with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications, and payments.”7

In other words: take today’s social media, add a splash of sophisticated 3D, fold in a plethora of options for entertainment and gaming, garnish it all with data-driven personalization, and you are all set to take away your order of a supersized social media network, the Metaverse.

Will it, won’t it?

Some experts predict that the Metaverse is going to take hold, whether we like it or not. If you haven’t, I strongly recommend watching the movie Ready Player One, to get an insight into what this new world could potentially look like. People will wake up, put on their VR headsets, enter a virtual world, and live their lives there, completely disconnected from reality.

In this new world, everything from our day-to-day lives will be virtually recreated: Work, play, entertainment, shopping, finance, real estate. The best part is, you can be who you want to be. Like I said, it’s social media, but you don’t even have to upload a picture of yourself. You can choose what avatar you want.

Sounds great! What’s the point of this article? Where’s the behavioral science in this?

Well, that’s the best part: no one knows. In the euphoria surrounding this cool, shiny, new thing, we have forgotten that, whether we’re talking about the Metaverse or social media or a good old-fashioned phone call, at the foundation of it all is human beings and hence, human behavior.

Anticipating the new world

My thesis behind writing this article is simple: We are blindsided by most new technologies. We don’t know what to expect, and we don’t know the implications they will have for human behavior until we reach a point of inflection, as in Rogers’s model of the diffusion of innovations.

When it comes to the Metaverse, however, we have the slight advantage of knowing that this new world will be built on existing social media. This is not to say that we’re not still vulnerable to unforeseen consequences — only that knowing social media somewhat well puts us in a position to preempt some of the Metaverse’s potential negative effects, instead of waiting for us to hit the inflexion point.

That being said, here, I will attempt to share the supersized version of the psychological effects of social media, as precursors to what we might face in the virtual world of the Metaverse.

The Disinhibition Effect, but ++

In the world of social media, the online disinhibition effect is fairly well documented.8 People say and do things in the online world that they would not normally do in “real life.” This can be relatively benign — say, people may voice more of their opinions, share more about their personal lives, and express their deepest feelings. But, it can also be harmful or toxic, as when people are more abusive and hateful online than they are in the real world.

The phenomenon of online trolling is an illustration of this effect. It is often attributed to invisibility: as a troll, no one knows who or where you are, so long as you choose not to reveal that. This anonymity gives people a sense of power and the confidence to say and do things they wouldn’t do otherwise.

Now imagine the Metaverse.

You are not just anonymous, but you are the best physical version of yourself, as is everyone else. You choose an avatar that embodies all the qualities you can only aspire towards in the real world. Breaking the rules suddenly becomes that much easier. Being abusive and rude to others, without facing the consequences, becomes that much more fun.

The highs and lows of life behind an avatar will be familiar to anyone who’s ever played online games like World of Warcraft or League of Legends. Roblox, an online gaming platform that has grown rapidly during the pandemic, provides many sobering illustrations of how the disinhibition effect can skew behavior.9 Even though the platform is directed at kids and teens, it’s become a breeding ground for anti-Semitism and radicalization.

If you thought getting rude comments on a post was bad, now imagine that in realistic 3D. In the Metaverse, nothing is stopping people from spitting on you or throwing their coffee at you if they don’t agree with you. Ouch.

The Echo Chamber, but ++

We have known about the echo chambers on social media for a while.10 Social media algorithms are designed to learn what you like and keep showing you content that fits that bill — which is to say, content that you are likely to agree with. Republicans see content on right-wing economic theory, while Democrats see the opposite. On the exact same issue, your social feed and mine could look completely different depending on what we’ve engaged with previously.

Because algorithms govern so much of what we see, we encounter opposing points of view less often.11 A direct implication of this is increased polarization, having a far-reaching impact on politics and society.12

Now imagine the Metaverse.

On social media, it was your feed that was biased. In the Metaverse, your whole world could be biased.

If you are against gun control, your world could be chock full of gun shops where you can buy whatever you want. If you are pro-choice, at that exact same spot where there was a gun shop, your world might have an abortion clinic. You will hang out at virtual bars with friends who are aligned only with your political ideology. You will be shown virtual stores of brands that target you with inventories personalized to your taste. Your bookstores and libraries will only show books you agree with.

Despite existing in the same virtual set up, your world and my world will be so different that what you see and live in, would be very different from what I do. We could walk by the same spot, but see two different worlds.13

In the 2D news feed, we absorb information, but retain only fuzzy traces, instead of details. In a 3D world, we retain the details — we remember everything in detail and what we remember is being trapped in a very vivid 3D echo chamber.14

A few years ago, Second Life, a virtual reality game, was all the rage. Ironically, even the creators of Second Life believe the current hype around the Metaverse could lead to a disaster because it grounds itself on the principles of extreme behavioral segmentation.

Self-presentation, but ++

On social media, we post our best pictures. We share our achievements. We use filters and make ourselves look good. We often look at others and think to ourselves that we need to up our game. We present ourselves in a certain way.16

A recent leak of internal documents from Facebook showed how pervasive this problem was, especially amongst teenagers. As per Facebook’s own admission, 32% of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse.17 Similarly, a recent study by Thomas Gültzow studied Instagram posts of young men and found that idealized images of “highly muscular, lean men,” received more likes and shares than content showing men who are less muscular or have more body fat.18

Now imagine the Metaverse.

The way you present yourself in the Metaverse has no connection to your real-world self. Maybe one day, you want to be Superman: you don the cape, up your muscle mass, and bingo, you’re good to go. The next day, maybe you feel like looking pretty, chic. No problem — find yourself a well-coiffed avatar, pick a stylish dress, and you’re all set.

To repeat, there is no connection to your real-world self. You exist in this world as an entirely new person. You can choose not to go to a gym for the rest of your life, but still walk around with biceps that make bodybuilders jealous. There is no limit here.

This is a gateway to body dysmorphia on steroids. What happens when we’re so accustomed to our gorgeous, fantasy selves that we can no longer stand to look at our imperfect, real-world faces and bodies? The implications will be far far worse for our psychology than we can imagine. Not just our personality, but our whole world collapses with it.

Dark Patterns, but ++

Remember the red dot notification? Oh, the unpredictability of not knowing who may have triggered that ping by liking your selfie or retweeing your hot take. The excitement of seeing what’s new in the feed. It’s a cycle that keeps pushing unpredictability to you, supplying you with the dopamine hits that keep you going. It’s literally like a drug. These are all examples of dark patterns and we have been talking about them.19

Now imagine the Metaverse.

You are seeing everything in 3D. Unpredictability in 3D. Who are you going to come across? Who is going to hug you? Who is going to cheer for you? Who are you hanging out with today? Will you meet a celebrity? Will you attend a concert? Will there be a high-octane car chase downtown? Will there be a bank robbery? You could be a part of literally any exciting event you want. And what does that do to your dopamine levels? That’s right. They will be elevated to ++, all the time. Each hit will be thrilling while it lasts, but it will only leave us ultimately wanting more, feeling unfulfilled without external stimulus.

Sorry if I made it look bleak…

… But the truth is, we need to learn from our experiences on social media. We were smart enough to study the harmful effects of social media and spread awareness of them, albeit slightly late. If we knowingly walk into the world of the Metaverse without fixing these problems, we will be doing ourselves a disservice. This is especially true for behavioral practitioners. We have the chance for an early start this time.

I don’t know when or if the Metaverse will take form. But I do know that if there’s even a slight chance of this happening, I would rather be on the inside, working actively to raise awareness of its potential pitfalls and building defenses against them, than to be on the outside and wait for the Netflix documentary about how we all got psychology wrong in the Metaverse.20

There’s no easy way to say this, but it looks like behavioral scientists are needed in the virtual world!

References

- Robertson, T. S. (1967). The process of innovation and the diffusion of innovation. Journal of marketing, 31(1), 14-19.

- https://about.fb.com/news/2021/10/facebook-company-is-now-meta/

- https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/19/microsoft-activision-what-satya-nadella-has-said-about-the-metaverse.html

- https://fortune.com/2022/03/16/hsbc-buys-land-in-metaverse-joins-jpmorgan-decentraland-sandbox/

- https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/03/how-the-1992-sci-fi-novel-snow-crash-predicted-facebooks-metaverse.html

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/apple-teases-metaverse-ar-plans-stock-jumps/articleshow/89169214.cms

- https://www.matthewball.vc/all/forwardtothemetaverseprimer

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & behavior, 7(3), 321-326.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60314572

- Cinelli, M., Morales, G. D. F., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9).

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/10/26/facebook-algorithm-conservative-liberal-extremes/

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-and-polarisation-literature-review

- https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-meta-metaverse-splinter-reality-more-2021-11

- https://www.pacteraedge.com/why-metaverse-must-be-mindful

- Lowry, P. B., Zhang, J., Wang, C., & Siponen, M. (2016). Why do adults engage in cyberbullying on social media? An integration of online disinhibition and deindividuation effects with the social structure and social learning model. Information Systems Research, 27(4), 962-986.

- Herring, S. C., & Kapidzic, S. (2015). Teens, gender, and self-presentation in social media. International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences, 2, 1-16.

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/sep/14/facebook-aware-instagram-harmful-effect-teenage-girls-leak-reveals

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/05/style/teen-bodybuilding-bigorexia-tiktok.html

- Macït, H. B., Macït, G., & Güngör, O. (2018). A research on social media addiction and dopamine driven feedback. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 5(3), 882-897.

- https://www.thesocialdilemma.com/

About the Author

Preeti Kotamarthi

Preeti Kotamarthi is the Behavioral Science Lead at Grab, the leading ride-hailing and mobile payments app in South East Asia. She has set up the behavioral practice at the company, helping product and design teams understand customer behavior and build better products. She completed her Masters in Behavioral Science from the London School of Economics and her MBA in Marketing from FMS Delhi. With more than 6 years of experience in the consumer products space, she has worked in a range of functions, from strategy and marketing to consulting for startups, including co-founding a startup in the rural space in India. Her main interest lies in popularizing behavioral design and making it a part of the product conceptualization process.