Is Automation Coming For Your Job?

The Jetsons dreamed of a futuristic utopia in which we would have flying cars and robots to take care of work and domestic tasks for us. And, as logically follows, we would have more free time than ever in this new, automated society.

But the future isn’t turning out anything similar to what we expected. Even before the pandemic hit, technology was supposed to free us from nonstop work. Instead, our devices became tools that kept us locked into work and spilled over into evenings and weekends. Looking into the future, we expect that automation will fill our workplaces, pushing out humans in favour of robots. How much of this is true? Is this idea of an automated world like The Jetsons — interesting to think about, but hopelessly outdated?

Most of us are worried about artificial intelligence (AI) making our jobs obsolete. I’m not immune to this kind of thinking — I actually think about it quite often, especially as a recession is nearing. After all, most of the buzz about AI focuses on the doom and gloom of a robot-driven future where humans have been pushed aside.1 But what if we’re asking the wrong questions about how AI will change our lives?

Asking if automation will make certain jobs obsolete implies that there is a possibility that these jobs will be completely taken over by AI and the rest will be left alone. This misrepresents both humans and AI technology: Automation will rarely get rid of entire jobs, but it will change nearly all of our careers in some way.

Let’s explore some new questions to find out about what automation may change and what will stay the same:

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices.

At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

Will AI eliminate my job?

Most likely, no. Entire jobs rarely get automated all at once. After all, jobs are a collection of tasks: A doctor’s job involves writing prescriptions, reviewing charts, talking to patients, and filling out paperwork, among many other things.2 Rarely, if ever, is a job only about completing one task. As we’ve seen throughout the last 200 years, some tasks (e.g., tilling soil) have been automated while others haven’t (e.g., raising children). Many of our daily tasks don’t exist in the same form as they did 40 or 50 years ago. Work as we know it is a continuous process of automation and adaptation, and so far very few entire jobs have been automated away with AI alone.3

Rather, AI will create new tasks and destroy existing ones, much like previous forms of automation, albeit at a rate that is potentially much faster than anything we’ve seen before.

So far, cycles of automation have changed the tasks we spend our time on, but we’ve always managed to bounce back and avoid mass unemployment. As it turns out, the economy can be quite resilient to structural change. Women are part of the workforce and people of colour have lower unemployment than in the 20th century, for example.4

Technology has automated some of the Western world’s most time-intensive tasks, like farming, manufacturing, bookkeeping, and data entry, as more workers found different jobs in the labour market. But the new jobs don’t look the same; and the tasks people work on have changed as well. Instead of replacing human workers, the automation process can lead us to discover more valuable, human-intensive tasks.5

Which of my tasks will be easier to automate, and which are more automation-resistant?

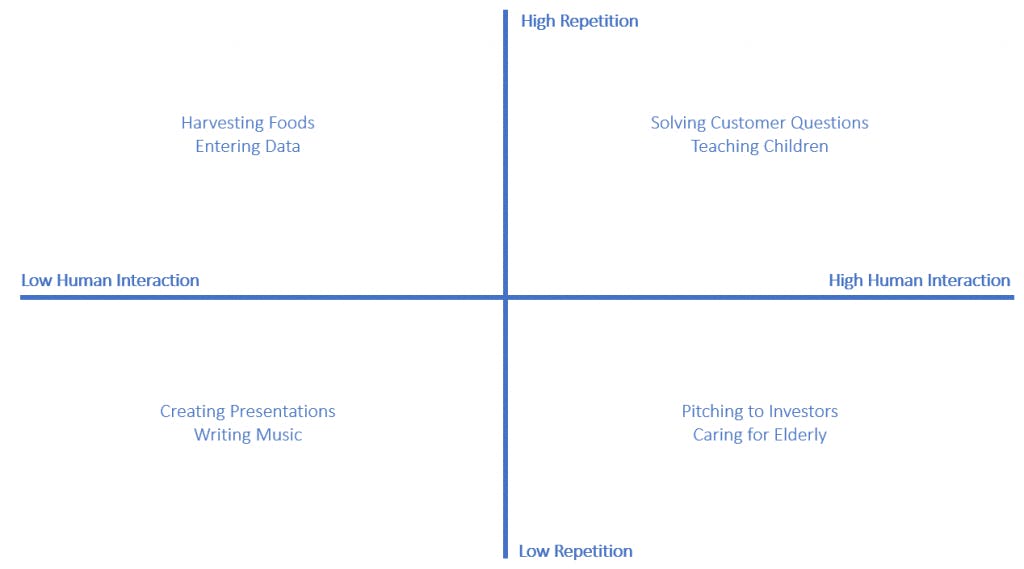

Controlled, repetitive tasks, like moving car parts and packaging food, are the kinds of tasks that can be easily taken over by robots. Tasks with complex human elements, like answering customer service calls or delivering a pitch to investors, will not be automated so quickly. Consider a two-by-two matrix of repetitiveness and human interaction: Tasks that are less repetitive and involve more human interaction won’t be taken over in the near future.

To understand where your job is going, analyze where it is right now. Job analysis is the process of understanding the tasks that make up a job, and the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to succeed at it. You can use this process to determine which of your job’s tasks have the highest risk of being automated. By doing so, you might be surprised by the tasks that computers aren’t so good at.6

Consider the following to analyze your job and understand how your set of work tasks may change:

- Which tasks take the most time?

- What skills do I need for each task?

- How easy is it to break down each task into a logical formula or a repetitive process that a computer could do?

- Now that some of my old tasks are automated, will I have any new responsibilities to keep the automated work running smoothly?

What new tasks might I start doing now that some of my work is automated?

Once simple and repetitive task are gone, what will be work on instead? Technological advances have saved receptionists time filing documents, which can now be spent serving as office managers. Sharing documents over the internet means that researchers can now access a journal article in three seconds instead of three weeks. This frees up researchers’ time to make more breakthroughs and explore their respective field more thoroughly.

The AI Governance Challenge

Taking automated tasks off of your plate can free up your time to do more valuable work. Instead of cleaning data and creating databases, data scientists could shift to communicating their insights to more people in their organization. If AI programs can read through thousands of legal cases, lawyers could spend more time crafting arguments and interviewing key people for their cases.

While more interesting and challenging tasks can get us into a flow state — where time flies and we find ourselves enjoying work8 — there’s a downside. Mind-wandering can actually help us be more creative.9 Stripping our work of the seemingly boring and less ‘useful’ tasks can lower our creativity. Instead, we should schedule occasional breaks from deep, intellectual work to give ourselves more time for creativity.

Consider the following to analyze what new tasks you’ll fill your time with due to automation:

- What high-value tasks am I not prioritizing right now because I spend so much time on repetitive yet necessary tasks?

- If I need to brainstorm, will my job still have downtime to explore new ideas?

- Where can I add times to let my mind wander and be more creative?

Takeaways

The way we talk about AI is steeped in fear. That’s because we’re facing a huge unknown that could change our work lives drastically. But we will get a much better, more personalized picture of our potential future if we go beyond the dichotomy of full automation or no automation. AI will impact each of us on a gradient — some of us will be less affected than others, based on the tasks our jobs are composed of. These changes are more likely to give us new work which requires our uniquely human skills, and will not simply leave us with less to do. Yet with this new set of responsibilities, we may lose the chance to turn boredom into creativity.

The good news is we can design our jobs so they motivate us and improve our well-being. As it turns out, we can design better jobs using principles from behavioral science.

References

- Wajcman, J. (2017). Automation: Is it really different this time? The British Journal of Sociology, 68(1), 119-127.

- Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279-1333.

- Brynjolfsson, E., Mitchell, T., & Rock, D. (2018, May). What can machines learn, and what does it mean for occupations and the economy?. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 108, pp. 43-47).

- Sangster, J. (2010). Transforming labour: Women and work in post-war Canada. University of Toronto Press; Freeman, R. B., Gordon, R. A., Bell, D., & Hall, R. E. (1973). Changes in the labor market for black Americans, 1948-72. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1973(1), 67-131.

- Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P. (2018). Artificial intelligence, automation and work (No. w24196). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Brynjolfsson, E. & Mitchell, T. (2017). What can machine learning do? Workforce implications. Science, 358(6370), 1530-1534.

- Singh, P. (2008). Job analysis for a changing workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 18(2), 87-99. & Landis, R. S., Fogli, L., & Goldberg, E. (1998). Future‐oriented job analysis: A description of the process and its organizational implications. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 6(3), 192-197.

- Basawapatna, A. R., Repenning, A., Koh, K. H., & Nickerson, H. (2013, August). The zones of proximal flow: guiding students through a space of computational thinking skills and challenges. In Proceedings of the ninth annual international ACM conference on International computing education research (pp. 67-74).

- Agnoli, S., Vanucci, M., Pelagatti, C., & Corazza, G. E. (2018). Exploring the link between mind wandering, mindfulness, and creativity: A multidimensional approach. Creativity Research Journal, 30(1), 41-53.

About the Author

Natasha Ouslis

Natasha is a behavior change consultant, writer, and researcher. She started her own workplace behavioral science consulting firm after working as a consultant at fast-growing behavioral economics companies including BEworks. Natasha is also finishing her PhD in organizational psychology at Western University, specializing in team conflict and collaboration, where she completed her Master of Science in the same field. She has a monthly column on workplace behavioral design in the Habit Weekly newsletter and is a Director and science translator at the nonprofit ScienceForWork.